The Art of Fantin Latour

basis of romanticism, moreover, was a horror of enjoyment from the smallest sketch of Ingres, or

reality and an ardent desire to avoid it. Nothing from one of Fantin Latour's admirable compositions

could be more untrue than the second part of this than from the Grasco-Roman "arrangements" of

proposition. The Romanticists of 1830 strove, as David? At the same time, I yield to no one in

many others, particularly Ingres, had striven since my admiration of the painter of the Sabines, when

1800, to recapture our natural language—to speak he keeps to his own subject, without borrowing

French, in a word. That the mysterious, the from elsewhere.

strange, the lugubrious, and the extravagant were When he first exhibited—in 1859—I think the

often unduly prominent is indisputable ; every members of the jury who had previously refused

protest is apt to overshoot the object at which it is his works must have felt some anxiety, not to say

directed. But the reformers of 1830, and more disquietude, at the sight of the public crowding

particularly the landscapists who were the precursors round his superb picture.

of the Courbets, the Manets, and the Fantins, From the day when Manet—who also had the

"personalised" the art which David and his honour of being rejected in 1859—gave his loyal

imitators had robbed of all personality, by prefer- support to the young artist, the professional daubers

ring direct observation to a regard for antique took fright; for their position was assailed, not by

traditions and dogmas. the public, but by the real artists, who had nothing

In all sincerity I ask—do we not derive more to do with the distribution of favours and orders.

No one is more insouciant,

and at the same time more

^^^^^^^^^ ^ " ^ r^ever occirired to him to

\, . ■ of Berlioz. One sees therein

the inspiration which is the

TjP*-- J^fjStP*^^ t"*"*** 4 result of studies made again

, "jr!k, ^**'\ ' ■ and again, corrected, re-

•.tfldSPS^^ PLr • .' touched, and finally ended at

'j^Sf^ flfew the moment when, with Nature

<«|W|^pjM^ BMImw as his guide, he has discovered

the realisation of his dreams.

■fci i$ jHl^. >( '• j The earliest of these inspira-

"iX" '">.'■■ tions—the scene from " Tann-

- „ . hauser" — was exhibited in

the same year as the ffo?nmage

Jjj^Lj { Ljp d Delacroix. In both these

compositions the artist has

summed up life with mar-

vellous acuteness of observa-

tion. The double current

which has constantly borne

Fantin Latour at once towards

the ideal and the real made

itself felt even in his earliest

works. But as he advanced

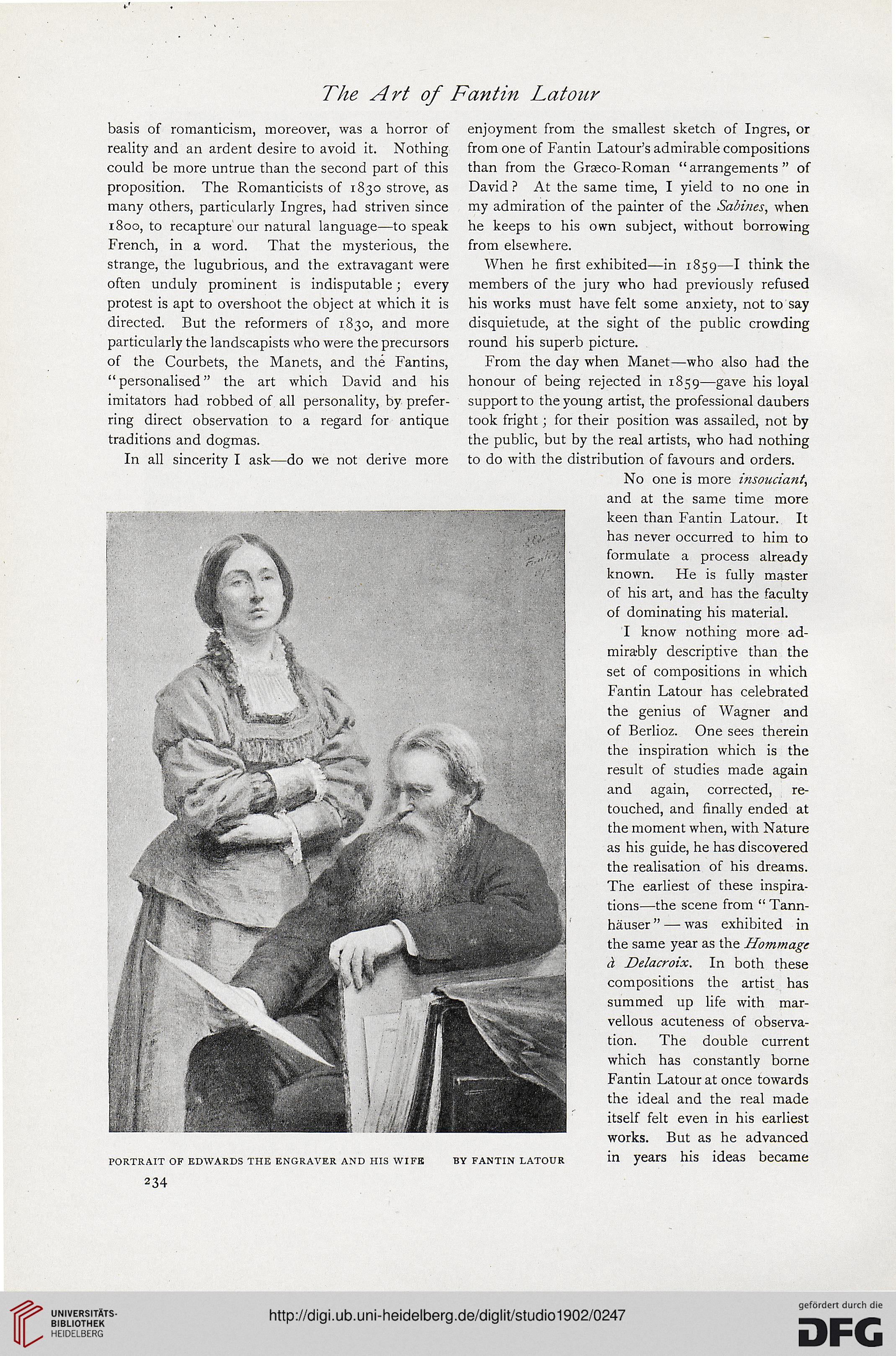

portrait of edwards the engraver and his wife by fantin latour in years his ideas became

234

basis of romanticism, moreover, was a horror of enjoyment from the smallest sketch of Ingres, or

reality and an ardent desire to avoid it. Nothing from one of Fantin Latour's admirable compositions

could be more untrue than the second part of this than from the Grasco-Roman "arrangements" of

proposition. The Romanticists of 1830 strove, as David? At the same time, I yield to no one in

many others, particularly Ingres, had striven since my admiration of the painter of the Sabines, when

1800, to recapture our natural language—to speak he keeps to his own subject, without borrowing

French, in a word. That the mysterious, the from elsewhere.

strange, the lugubrious, and the extravagant were When he first exhibited—in 1859—I think the

often unduly prominent is indisputable ; every members of the jury who had previously refused

protest is apt to overshoot the object at which it is his works must have felt some anxiety, not to say

directed. But the reformers of 1830, and more disquietude, at the sight of the public crowding

particularly the landscapists who were the precursors round his superb picture.

of the Courbets, the Manets, and the Fantins, From the day when Manet—who also had the

"personalised" the art which David and his honour of being rejected in 1859—gave his loyal

imitators had robbed of all personality, by prefer- support to the young artist, the professional daubers

ring direct observation to a regard for antique took fright; for their position was assailed, not by

traditions and dogmas. the public, but by the real artists, who had nothing

In all sincerity I ask—do we not derive more to do with the distribution of favours and orders.

No one is more insouciant,

and at the same time more

^^^^^^^^^ ^ " ^ r^ever occirired to him to

\, . ■ of Berlioz. One sees therein

the inspiration which is the

TjP*-- J^fjStP*^^ t"*"*** 4 result of studies made again

, "jr!k, ^**'\ ' ■ and again, corrected, re-

•.tfldSPS^^ PLr • .' touched, and finally ended at

'j^Sf^ flfew the moment when, with Nature

<«|W|^pjM^ BMImw as his guide, he has discovered

the realisation of his dreams.

■fci i$ jHl^. >( '• j The earliest of these inspira-

"iX" '">.'■■ tions—the scene from " Tann-

- „ . hauser" — was exhibited in

the same year as the ffo?nmage

Jjj^Lj { Ljp d Delacroix. In both these

compositions the artist has

summed up life with mar-

vellous acuteness of observa-

tion. The double current

which has constantly borne

Fantin Latour at once towards

the ideal and the real made

itself felt even in his earliest

works. But as he advanced

portrait of edwards the engraver and his wife by fantin latour in years his ideas became

234