THE JAPANESE GARDEN

For centuries the Nippon garden, in its

development, has been infused with reli-

gious ideas. The aesthetic law in the art

of gardening was formulated after a careful

study of long practice. That law requires

the main rock to be placed at a certain spot

in the garden, and the other rocks of re-

quired shapes and sizes are to be distri-

buted in their relation to the principal

rock according to the law, more or less

strictly adhered to. It is the same with

trees. When the relative position of one

rock to the other has become fixed, more

or less, according to the aesthetic law, in

order to augment that law and to save the

trouble of explaining why and how, master

gardeners of old have named different rocks

and trees, according to their position in the

garden, and many of these names are de-

rived from religion. One should not

be misled by the terms used to believe

that the gardens of the Nippon style are

based on the Buddhistic religion. But

because of religious terms employed to

explain the law of beauty, the mind of the

observer is easily turned to religious and

philosophical contemplation. Thus the

garden not only furnishes enjoyment to

the physical eye, but it also affords and

stimulates spiritual contemplation. a

Space does not permit a detailed ex-

planation of so complicated a technique

as garden construction. It must suffice to

say here that, generally speaking, there

should be (i) the main mountain in the

landscape gardening which should form a

ravine, with another where a waterfall is

formed, and there should be another hill

back of it; (2) the main mountain may

be drawn out to form an easy slope to

provide for a chin, a rustic resting place ;

(3) a path may be made along the edge of

the pond to suggest the road at the foot

of the hill; (4) sometimes a precipice is

created between the main mountain and

the hill that adjoins it; (5) the principal

mountain may be supported by subsidiary

ones on the back and on either side, semi-

circling the lake and projecting into it.

Such is the customary lay-out of the hills.

As to the rocks, though gardeners do not

always agree with the names, Sanzon-seki

(rocks representing the Buddhistic trinity)

should occupy the most prominent place

in the garden. There should be getsuin-seki

268

(moon shadow rock) on the distant hill top.

More in the foreground, facing the pro-

tecting rocks, there should be reihai-seki

(the worshipping rock). There are more

than a score of other specially named rocks,

and a multitude of nameless ones, used to

construct the garden. Stepping stones con-

stitute a very important factor, especially

in small gardens. a a a a

As to the trees, behind the main rock or

a group of rocks there should be planted

the principal tree, or group of trees.

Because of the important position they

occupy, they are called shomaki, or shoshin-

boku (right true tree) and should have an

excellent form. There should be a group

of trees called takigakoi-gi (waterfall en-

closing trees) partly to hide the waterfall

and to form a deep shadow necessary for

the sylvan retreat. A few branches should

extend across the front of the waterfall

partly to conceal the falling water. Sekiyo-

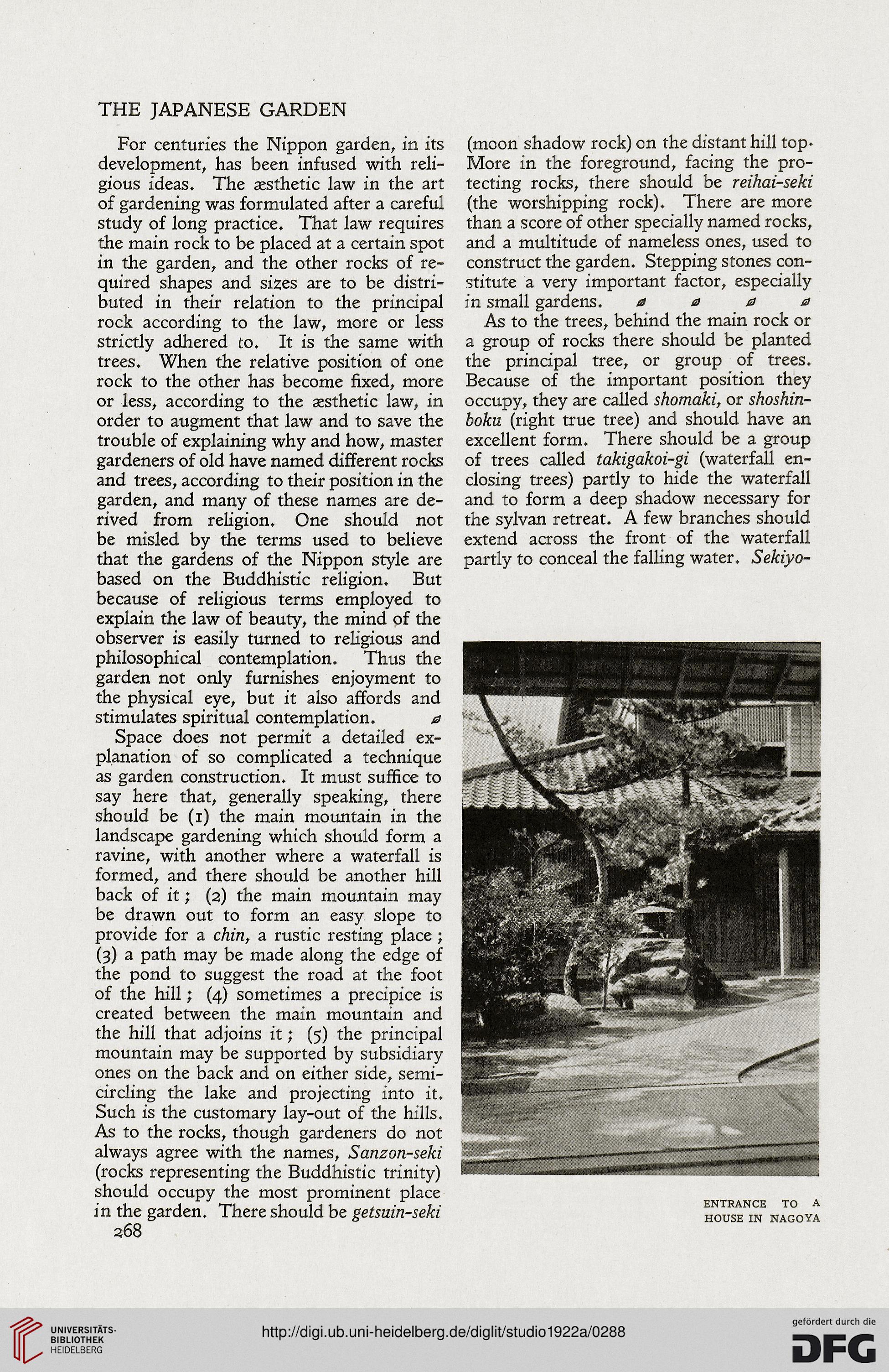

ENTRANCE TO A

HOUSE IN NAGOYA

For centuries the Nippon garden, in its

development, has been infused with reli-

gious ideas. The aesthetic law in the art

of gardening was formulated after a careful

study of long practice. That law requires

the main rock to be placed at a certain spot

in the garden, and the other rocks of re-

quired shapes and sizes are to be distri-

buted in their relation to the principal

rock according to the law, more or less

strictly adhered to. It is the same with

trees. When the relative position of one

rock to the other has become fixed, more

or less, according to the aesthetic law, in

order to augment that law and to save the

trouble of explaining why and how, master

gardeners of old have named different rocks

and trees, according to their position in the

garden, and many of these names are de-

rived from religion. One should not

be misled by the terms used to believe

that the gardens of the Nippon style are

based on the Buddhistic religion. But

because of religious terms employed to

explain the law of beauty, the mind of the

observer is easily turned to religious and

philosophical contemplation. Thus the

garden not only furnishes enjoyment to

the physical eye, but it also affords and

stimulates spiritual contemplation. a

Space does not permit a detailed ex-

planation of so complicated a technique

as garden construction. It must suffice to

say here that, generally speaking, there

should be (i) the main mountain in the

landscape gardening which should form a

ravine, with another where a waterfall is

formed, and there should be another hill

back of it; (2) the main mountain may

be drawn out to form an easy slope to

provide for a chin, a rustic resting place ;

(3) a path may be made along the edge of

the pond to suggest the road at the foot

of the hill; (4) sometimes a precipice is

created between the main mountain and

the hill that adjoins it; (5) the principal

mountain may be supported by subsidiary

ones on the back and on either side, semi-

circling the lake and projecting into it.

Such is the customary lay-out of the hills.

As to the rocks, though gardeners do not

always agree with the names, Sanzon-seki

(rocks representing the Buddhistic trinity)

should occupy the most prominent place

in the garden. There should be getsuin-seki

268

(moon shadow rock) on the distant hill top.

More in the foreground, facing the pro-

tecting rocks, there should be reihai-seki

(the worshipping rock). There are more

than a score of other specially named rocks,

and a multitude of nameless ones, used to

construct the garden. Stepping stones con-

stitute a very important factor, especially

in small gardens. a a a a

As to the trees, behind the main rock or

a group of rocks there should be planted

the principal tree, or group of trees.

Because of the important position they

occupy, they are called shomaki, or shoshin-

boku (right true tree) and should have an

excellent form. There should be a group

of trees called takigakoi-gi (waterfall en-

closing trees) partly to hide the waterfall

and to form a deep shadow necessary for

the sylvan retreat. A few branches should

extend across the front of the waterfall

partly to conceal the falling water. Sekiyo-

ENTRANCE TO A

HOUSE IN NAGOYA