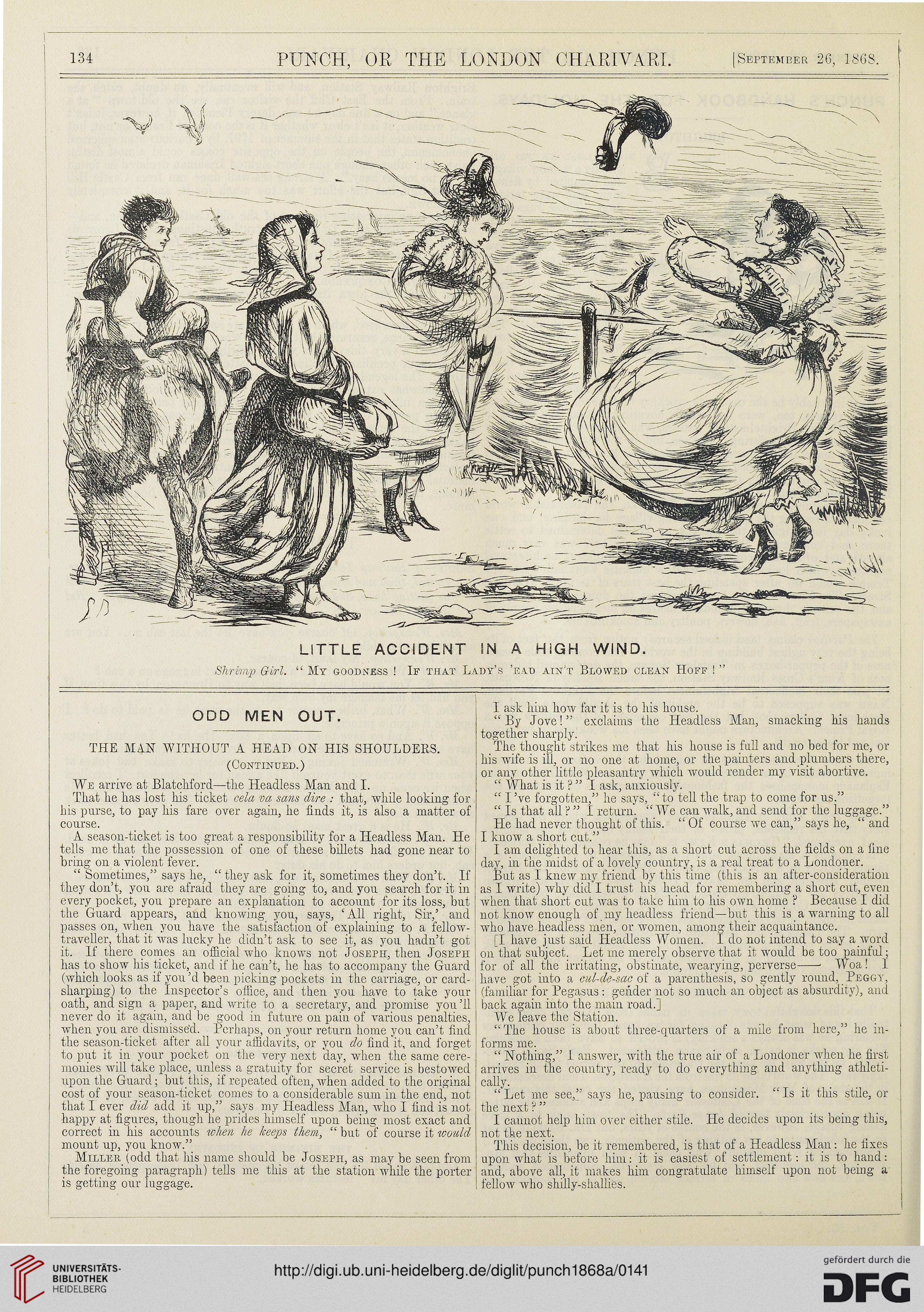

LITTLE ACCIDENT IN A HIGH WIND.

Shrimp Girl. “ My goodness ! If that Lady’s ’ead ain’t Bloyved clean Hoff ! ’’

ODD MEN OUT.

THE MA.N WITHOUT A HEAD ON HIS SHOULDERS.

(Continued.)

We arrive at Blatckford—the Headless Man and I.

That he has lost his ticket cela va sans dire : that, while looking for

his purse, to pay his fare over again, he finds it, is also a matter of

course.

A season-ticket is too great a responsibility for a Headless Man. He

tells me that the possession of one of these billets had gone near to

bring on a violent fever.

“ Sometimes,” says he, “ they ask for it, sometimes they don’t. If

they don’t, you are afraid they are going to, and you search for it in

every pocket, you prepare an explanation to account for its loss, but

the Guard appears, and knowing you, says, ‘All_ right, Sir,’ and

passes on, when you have the satisfaction of explaining to a fellow-

traveller, that it was lucky he didn’t ask to see it, as you hadn’t got

it. If there comes an official who knows not Joseph, then Joseph

has to show his ticket, and if he can’t, he has to accompany the Guard

(which looks as if you’d been picking pockets in the carriage, or card-

sharping) to the Inspector’s office, and then you have to take your

oath, and sign a. paper, and write to a secretary, and promise you ’ll

never do it again, and be good in future on pain of various penalties,

when you are dismissed. Perhaps, on your return home you can’t find

the season-ticket after all your affidavits, or you do find it, and forget

to put it in your pocket on the very next day, when the same cere-

monies will take place, unless a gratuity for secret service is bestowed

upon the Guard; but this, if repeated often, when added to the original

cost of your season-ticket comes to a considerable sum in the end, not

that I ever did add it up,” says my Headless Man, who I find is not

happy at figures, though he prides himself upon being most exact and

correct in his accounts when he keeps them, “ but of course it would

mount up, you know.”

Miller (odd that his name should be Joseph, as may be seen from

the foregoing paragraph) tells me this at the station while the porter

is getting our luggage.

I ask him how far it is to his house.

“By Jove!” exclaims the Eteadless Man, smacking his hands

together sharply.

The thought strikes me that his house is full and no bed for me, or

his wife is ill, or no one at home, or the painters and plumbers there,

or any other little pleasantry.which would render my visit abortive.

“ What is it ? ” I ask, anxiously.

“ I’ve forgotten,” he says, “to tell the trap to come for us.”

“ Is that all ? ” I return. “We can walk, and send for the luggage.”

Pie had never thought of this. “ Of course we can,” says he, “ and

I know a short cut.”

I am delighted to hear this, as a short cut across the fields on a fine

day, in the midst of a lovely country, is a real treat to a Londoner.

But as I knew my friend by this time (this is an after-consideration

as I write) why did I trust his head for remembering a short cut, even

when that short cut was to take him to his own home ? Because I did

not know enough of my headless friend—but this is a warning to all

who have headless men, or women, among their acquaintance.

[I have just said Headless Women. I do not intend to say a word

on that subject. Let me merely observe that it would be too painful;

for of all the irritating, obstinate, wearying, perverse-- Woa! I

have got into a cul-de-sac of a parenthesis, so gently round, Peggy,

(familiar for Pegasus: gender not so much an object as absurdity), and

back again into the main road.]

We leave the Station.

“The house is about three-quarters of a mile from here,” he in-

forms me.

“ Nothing,” I answer, with the true air of a Londoner when he first

arrives in the country, ready to do everything and anything athleti-

cally.

“ Let me see,” says he, pausing to consider. “ Is it this stile, or

the next ? ”

I cannot help him over either stile. He decides upon its being this,

not the next.

This decision, be it remembered, is that of a Headless Man: he fixes

upon what is before him: it is easiest of settlement: it is to hand:

and, above all, it makes him congratulate himself upon not being a

fellow who shilly-shallies.

Shrimp Girl. “ My goodness ! If that Lady’s ’ead ain’t Bloyved clean Hoff ! ’’

ODD MEN OUT.

THE MA.N WITHOUT A HEAD ON HIS SHOULDERS.

(Continued.)

We arrive at Blatckford—the Headless Man and I.

That he has lost his ticket cela va sans dire : that, while looking for

his purse, to pay his fare over again, he finds it, is also a matter of

course.

A season-ticket is too great a responsibility for a Headless Man. He

tells me that the possession of one of these billets had gone near to

bring on a violent fever.

“ Sometimes,” says he, “ they ask for it, sometimes they don’t. If

they don’t, you are afraid they are going to, and you search for it in

every pocket, you prepare an explanation to account for its loss, but

the Guard appears, and knowing you, says, ‘All_ right, Sir,’ and

passes on, when you have the satisfaction of explaining to a fellow-

traveller, that it was lucky he didn’t ask to see it, as you hadn’t got

it. If there comes an official who knows not Joseph, then Joseph

has to show his ticket, and if he can’t, he has to accompany the Guard

(which looks as if you’d been picking pockets in the carriage, or card-

sharping) to the Inspector’s office, and then you have to take your

oath, and sign a. paper, and write to a secretary, and promise you ’ll

never do it again, and be good in future on pain of various penalties,

when you are dismissed. Perhaps, on your return home you can’t find

the season-ticket after all your affidavits, or you do find it, and forget

to put it in your pocket on the very next day, when the same cere-

monies will take place, unless a gratuity for secret service is bestowed

upon the Guard; but this, if repeated often, when added to the original

cost of your season-ticket comes to a considerable sum in the end, not

that I ever did add it up,” says my Headless Man, who I find is not

happy at figures, though he prides himself upon being most exact and

correct in his accounts when he keeps them, “ but of course it would

mount up, you know.”

Miller (odd that his name should be Joseph, as may be seen from

the foregoing paragraph) tells me this at the station while the porter

is getting our luggage.

I ask him how far it is to his house.

“By Jove!” exclaims the Eteadless Man, smacking his hands

together sharply.

The thought strikes me that his house is full and no bed for me, or

his wife is ill, or no one at home, or the painters and plumbers there,

or any other little pleasantry.which would render my visit abortive.

“ What is it ? ” I ask, anxiously.

“ I’ve forgotten,” he says, “to tell the trap to come for us.”

“ Is that all ? ” I return. “We can walk, and send for the luggage.”

Pie had never thought of this. “ Of course we can,” says he, “ and

I know a short cut.”

I am delighted to hear this, as a short cut across the fields on a fine

day, in the midst of a lovely country, is a real treat to a Londoner.

But as I knew my friend by this time (this is an after-consideration

as I write) why did I trust his head for remembering a short cut, even

when that short cut was to take him to his own home ? Because I did

not know enough of my headless friend—but this is a warning to all

who have headless men, or women, among their acquaintance.

[I have just said Headless Women. I do not intend to say a word

on that subject. Let me merely observe that it would be too painful;

for of all the irritating, obstinate, wearying, perverse-- Woa! I

have got into a cul-de-sac of a parenthesis, so gently round, Peggy,

(familiar for Pegasus: gender not so much an object as absurdity), and

back again into the main road.]

We leave the Station.

“The house is about three-quarters of a mile from here,” he in-

forms me.

“ Nothing,” I answer, with the true air of a Londoner when he first

arrives in the country, ready to do everything and anything athleti-

cally.

“ Let me see,” says he, pausing to consider. “ Is it this stile, or

the next ? ”

I cannot help him over either stile. He decides upon its being this,

not the next.

This decision, be it remembered, is that of a Headless Man: he fixes

upon what is before him: it is easiest of settlement: it is to hand:

and, above all, it makes him congratulate himself upon not being a

fellow who shilly-shallies.

Werk/Gegenstand/Objekt

Titel

Titel/Objekt

Little accident in a high wind

Weitere Titel/Paralleltitel

Serientitel

Punch

Sachbegriff/Objekttyp

Inschrift/Wasserzeichen

Aufbewahrung/Standort

Aufbewahrungsort/Standort (GND)

Inv. Nr./Signatur

H 634-3 Folio

Objektbeschreibung

Maß-/Formatangaben

Auflage/Druckzustand

Werktitel/Werkverzeichnis

Herstellung/Entstehung

Künstler/Urheber/Hersteller (GND)

Entstehungsdatum

um 1868

Entstehungsdatum (normiert)

1863 - 1873

Entstehungsort (GND)

Auftrag

Publikation

Fund/Ausgrabung

Provenienz

Restaurierung

Sammlung Eingang

Ausstellung

Bearbeitung/Umgestaltung

Thema/Bildinhalt

Thema/Bildinhalt (GND)

Literaturangabe

Rechte am Objekt

Aufnahmen/Reproduktionen

Künstler/Urheber (GND)

Reproduktionstyp

Digitales Bild

Rechtsstatus

Public Domain Mark 1.0

Creditline

Punch, 55.1868, September 26, 1868, S. 134

Beziehungen

Erschließung

Lizenz

CC0 1.0 Public Domain Dedication

Rechteinhaber

Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg