April 23, 1859 J PUNCH, OR THE LONDON CHARIVARI. l«l

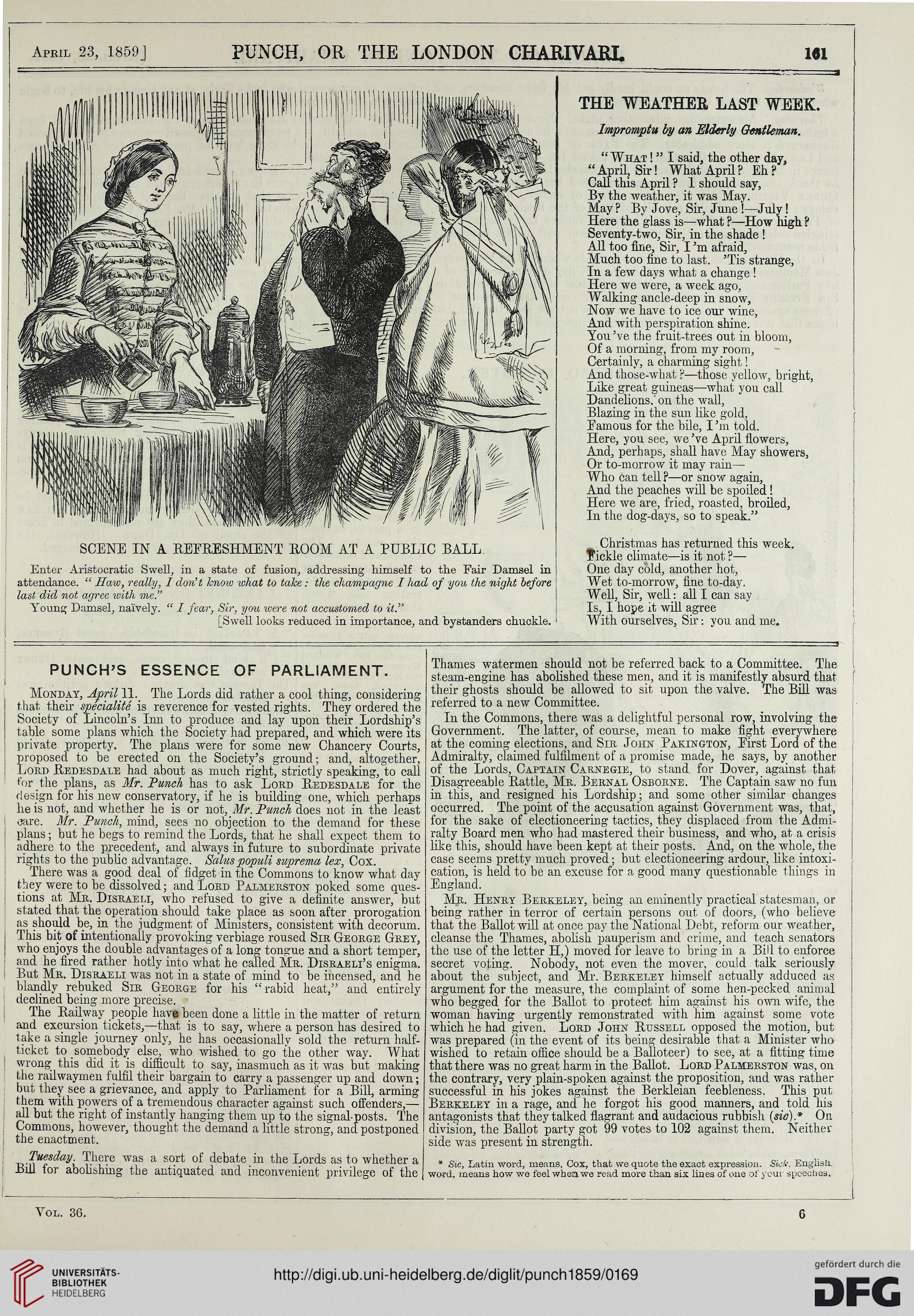

SCENE IN A REFRESHMENT ROOM AT A PUBLIC BALL

Enter Aristocratic Swell, in a state of fusion, addressing himself to the Fair Damsel in

attendance. " Haw, really, I don't know lohat to take: the champagne I had of you the night before

last did not agree icith me."

Young; Damsel, naively. " / fear, Sir, you toere not accustomed to it.'"

[Swell looks reduced in importance, and bystanders chuckle.

THE WEATHER LAST WEEK.

Impromptu by an Elderly Gentleman.

" What !" I said, the other day,

" April, Sir! What April ? Eh ?

Call this April ? 1 should say,

By the weather, it was May.

May? By Jove, Sir, June !—July!

Here the glass is—what ?—How nigh ?

Seventy-two, Sir, in the shade !

All too fine, Sir, I'm afraid,

Much too fine to last. 'Tis strange,

In a few days what a change !

Here we were, a week ago,

Walking ancle-deep in snow,

Now we have to ice our wine,

And with perspiration shine.

You've the fruit-trees out in bloom,

Of a morning, from my room,

Certainly, a charming sight!

And those-what ?—those yellow, bright,

Like great guineas—what you call

Dandelions.'on the wall,

Blazing in the sun like gold,

Eamous for the bile, I'm told.

Here, you see, we've April flowers,

And, perhaps, shall have May showers,

Or to-morrow it may rain—

Who can tell ?—or snow again,

And the peaches will be spoiled!

Here we are, fried, roasted, broiled,

In the dog-days, so to speak."

Christmas has returned this week,

fickle climate—is it not ?—

One day cold, another hot,

Wet to-morrow, fine to-day.

Well, Sir, well: all I can say

Is, I hope it will agree

With ourselves, Sir: you and me.

PUNCH'S ESSENCE OF PARLIAMENT.

Monday, April 11. The Lords did rather a cool thing, considering

that then- specialite is reverence for vested rights. They ordered the

Society of Lincoln's_ Inn to produce and lay upon their Lordship's

table some plans which the Society had prepared, and which were its

private property. The plans were for some new Chancery Courts,

proposed to be erected on the Society's ground; and, altogether,

Lord Redesdale had about as much right, strictly speaking, to call

for the plans, as Mr. Punch has to ask Lord Redesdale for the

design for his new conservatory, if he is building one, which perhaps

he is not, and whether he is or not, Mr. Punch does not in the least

oare. Mr. Punch, mind, sees no objection to the demand for these

plans; but he begs to remind the Lords, that he shall expect them to

adhere to the precedent, and always in future to subordinate private

rights to the public advantage. Saluspopuli suprema lex, Cox.

There was a good deal of fidget in the Commons to know what day

they were to be dissolved; and Lord Palmerston poked some ques-

tions at Mr. Disraeli, who refused to give a definite answer, but

stated that the operation should take place as soon after prorogation

as should be, in the judgment of Ministers, consistent with decorum.

This bit of intentionally provoking verbiage roused Sir George Grey,

who enjoys the double advantages of a long tongue and a short temper,

and he fired rather hotly into what he called Mr. Disraeli's enigma.

But Mr. Disraeli was not in a state of mind to be incensed, and he

blandly rebuked Sir George for his "rabid heat," and entirely

declined being more precise.

The Railway people hav» been done a little in the matter of return

and excursion tickets,—that is to say, where a person has desired to

take a single journey only, he has occasionally sold the return half-

ticket to somebody else, who wished to go the other way. What

wrong this did it is difficult to say, inasmuch as it was but making

the railwaymen fulfil their bargain to carry a passenger up and down;

but they see a grievance, and apply to Parliament for a Bill, arming

them with powers of a tremendous character against such offenders,—

all but the right of instantly hanging them up to the signal-posts. The

Commons, however, thought the demand a little strong, and postponed

the enactment.

Tuesday. There was a sort of debate in the Lords as to whether a

Bill for abolishing the antiquated and inconvenient privilege of the

Thames watermen should not be referred back to a Committee. The

steam-engine has abolished these men, and it is manifestly absurd that

their ghosts should be allowed to sit upon the valve. The Bill was

referred to a new Committee.

In the Commons, there was a delightful personal row, involving the

Government. The latter, of course, mean to make fight everywhere

at the coming elections, and Sir John Pakington, Eirst Lord of the

Admiralty, claimed fulfilment of a promise made, he says, by another

of the Lords, Captain Carnegie, to stand for Dover, against that

Disagreeable Rattle, Mr. Bernal Osborne. The Captain saw no fun

in this, and resigned his Lordship; and some other similar changes

occurred. The point of the accusation against Government was, that,

for the sake of electioneering tactics, they displaced from the Admi-

ralty Board men who had mastered their business, and who, at a crisis

like this, should have been kept at their posts. And, on the whole, the

case seems pretty much proved; but electioneering ardour, like intoxi-

cation, is held to be an excuse for a good many questionable things in

England.

Mr. Henry Berkeley, being an eminently practical statesman, or

being rather in terror of certain persons out of doors, (who believe

that the Ballot will at once pay the National Debt, reform our weather,

cleanse the Thames, abolish pauperism and crime, and teach senators

the use of the letter H,) moved for leave to bring in a Bill to enforce

secret voting. Nobody, not even the mover, could talk seriously

about the subject, and Mr. Berkeley himself actually adduced as

argument for the measure, the complaint of some hen-pecked animal

who begged for the Ballot to protect him against his own wife, the

woman having urgently remonstrated with him against some vote

which he had given. Lord John Russell opposed the motion, but

was prepared (in the event of its being desirable that a Minister who

wished to retain office should be a Balloteer) to see, at a fitting time

that there was no great harm in the Ballot. Lord Palmerston was, on

the contrary, very plain-spoken against the proposition, and was rather

successful in his jokes against the Berkleian feebleness. This put

Berkeley in a rage, and he forgot his good manners, and told his

antagonists that they talked flagrant and audacious rubbish (sio).* On

division, the Ballot party got 99 votes to 102 against them. Neither

side was present in strength.

* Sic, Latin word, means. Cox, that we quote the exact expression. SicS, English,

word, means how wo feel whea we read more than six lines of one of your speeches.

Vol. 36.

6

SCENE IN A REFRESHMENT ROOM AT A PUBLIC BALL

Enter Aristocratic Swell, in a state of fusion, addressing himself to the Fair Damsel in

attendance. " Haw, really, I don't know lohat to take: the champagne I had of you the night before

last did not agree icith me."

Young; Damsel, naively. " / fear, Sir, you toere not accustomed to it.'"

[Swell looks reduced in importance, and bystanders chuckle.

THE WEATHER LAST WEEK.

Impromptu by an Elderly Gentleman.

" What !" I said, the other day,

" April, Sir! What April ? Eh ?

Call this April ? 1 should say,

By the weather, it was May.

May? By Jove, Sir, June !—July!

Here the glass is—what ?—How nigh ?

Seventy-two, Sir, in the shade !

All too fine, Sir, I'm afraid,

Much too fine to last. 'Tis strange,

In a few days what a change !

Here we were, a week ago,

Walking ancle-deep in snow,

Now we have to ice our wine,

And with perspiration shine.

You've the fruit-trees out in bloom,

Of a morning, from my room,

Certainly, a charming sight!

And those-what ?—those yellow, bright,

Like great guineas—what you call

Dandelions.'on the wall,

Blazing in the sun like gold,

Eamous for the bile, I'm told.

Here, you see, we've April flowers,

And, perhaps, shall have May showers,

Or to-morrow it may rain—

Who can tell ?—or snow again,

And the peaches will be spoiled!

Here we are, fried, roasted, broiled,

In the dog-days, so to speak."

Christmas has returned this week,

fickle climate—is it not ?—

One day cold, another hot,

Wet to-morrow, fine to-day.

Well, Sir, well: all I can say

Is, I hope it will agree

With ourselves, Sir: you and me.

PUNCH'S ESSENCE OF PARLIAMENT.

Monday, April 11. The Lords did rather a cool thing, considering

that then- specialite is reverence for vested rights. They ordered the

Society of Lincoln's_ Inn to produce and lay upon their Lordship's

table some plans which the Society had prepared, and which were its

private property. The plans were for some new Chancery Courts,

proposed to be erected on the Society's ground; and, altogether,

Lord Redesdale had about as much right, strictly speaking, to call

for the plans, as Mr. Punch has to ask Lord Redesdale for the

design for his new conservatory, if he is building one, which perhaps

he is not, and whether he is or not, Mr. Punch does not in the least

oare. Mr. Punch, mind, sees no objection to the demand for these

plans; but he begs to remind the Lords, that he shall expect them to

adhere to the precedent, and always in future to subordinate private

rights to the public advantage. Saluspopuli suprema lex, Cox.

There was a good deal of fidget in the Commons to know what day

they were to be dissolved; and Lord Palmerston poked some ques-

tions at Mr. Disraeli, who refused to give a definite answer, but

stated that the operation should take place as soon after prorogation

as should be, in the judgment of Ministers, consistent with decorum.

This bit of intentionally provoking verbiage roused Sir George Grey,

who enjoys the double advantages of a long tongue and a short temper,

and he fired rather hotly into what he called Mr. Disraeli's enigma.

But Mr. Disraeli was not in a state of mind to be incensed, and he

blandly rebuked Sir George for his "rabid heat," and entirely

declined being more precise.

The Railway people hav» been done a little in the matter of return

and excursion tickets,—that is to say, where a person has desired to

take a single journey only, he has occasionally sold the return half-

ticket to somebody else, who wished to go the other way. What

wrong this did it is difficult to say, inasmuch as it was but making

the railwaymen fulfil their bargain to carry a passenger up and down;

but they see a grievance, and apply to Parliament for a Bill, arming

them with powers of a tremendous character against such offenders,—

all but the right of instantly hanging them up to the signal-posts. The

Commons, however, thought the demand a little strong, and postponed

the enactment.

Tuesday. There was a sort of debate in the Lords as to whether a

Bill for abolishing the antiquated and inconvenient privilege of the

Thames watermen should not be referred back to a Committee. The

steam-engine has abolished these men, and it is manifestly absurd that

their ghosts should be allowed to sit upon the valve. The Bill was

referred to a new Committee.

In the Commons, there was a delightful personal row, involving the

Government. The latter, of course, mean to make fight everywhere

at the coming elections, and Sir John Pakington, Eirst Lord of the

Admiralty, claimed fulfilment of a promise made, he says, by another

of the Lords, Captain Carnegie, to stand for Dover, against that

Disagreeable Rattle, Mr. Bernal Osborne. The Captain saw no fun

in this, and resigned his Lordship; and some other similar changes

occurred. The point of the accusation against Government was, that,

for the sake of electioneering tactics, they displaced from the Admi-

ralty Board men who had mastered their business, and who, at a crisis

like this, should have been kept at their posts. And, on the whole, the

case seems pretty much proved; but electioneering ardour, like intoxi-

cation, is held to be an excuse for a good many questionable things in

England.

Mr. Henry Berkeley, being an eminently practical statesman, or

being rather in terror of certain persons out of doors, (who believe

that the Ballot will at once pay the National Debt, reform our weather,

cleanse the Thames, abolish pauperism and crime, and teach senators

the use of the letter H,) moved for leave to bring in a Bill to enforce

secret voting. Nobody, not even the mover, could talk seriously

about the subject, and Mr. Berkeley himself actually adduced as

argument for the measure, the complaint of some hen-pecked animal

who begged for the Ballot to protect him against his own wife, the

woman having urgently remonstrated with him against some vote

which he had given. Lord John Russell opposed the motion, but

was prepared (in the event of its being desirable that a Minister who

wished to retain office should be a Balloteer) to see, at a fitting time

that there was no great harm in the Ballot. Lord Palmerston was, on

the contrary, very plain-spoken against the proposition, and was rather

successful in his jokes against the Berkleian feebleness. This put

Berkeley in a rage, and he forgot his good manners, and told his

antagonists that they talked flagrant and audacious rubbish (sio).* On

division, the Ballot party got 99 votes to 102 against them. Neither

side was present in strength.

* Sic, Latin word, means. Cox, that we quote the exact expression. SicS, English,

word, means how wo feel whea we read more than six lines of one of your speeches.

Vol. 36.

6