dated to the time of Prior Wibert (c. 1153-1167), and the

paintings in both chapels to the same period.11 The complexity

of these dating problems is compounded by the magnificent

painting of St Paul and the Viper (fig. 1) in St Anselm’s Chapel,

which does indeed seem likely to be coeval with the insertions,

but for which particularly close stylistic parallels are provided

by the Bury Bible - formerly thought to date from c. 1160,

but now from c. 1130.12 The painting of St Paul is in a more

advanced style than that of the St Gabriel’s apse decoration,

showing, for example, the elegant ’clinging curvilinear’ variety

of damp fold, but it is by no means certain that it is much if

at all later in date. Could it be, in fact, that both paintings

date from c. 1130, and thus survive from the phase of the

Cathedral’s decoration so eloquently described by William of

Malmesbury?13 The current programme of research will exa-

mine the types of stone employed for the insertions and ori-

ginal building, and the tooling of this stonework and the man-

ner in which the insertions were effected, in order to try to

determine whether the alterations might indeed be of this

early date, or perhaps changes carried out during the original

building campaign rather than at some later time.

The Paintings in the Nave

Curiously, the apse of St Gabriel’s Chapel was blocked off

from the nave by a wall, apparently at a very early date, since

the altar is not mentioned by Gervase of Canterbury in his

otherwise fairly complete description of the cathedral written

c. 1199.14This wall remained in place until as late as 1952 (fig.

9), and before a doorway was inserted in 1878, the only means

of access to the apse was by a small opening of about 45 x

55 cm on the south side. It would scarcely make sense if the

wall had been built immediately after the apse was elaborately

decorated, and in fact, there is evidence of painting forming

part of the same scheme on the east wall of the nave, where

remains of the characteristic dado draperies with jewelled

border are still visible.

The main survivals of Romanesque painting in the nave, how-

ever, are on the two western bays of the vault (fig. 10). These

paintings probably date from c. 1180 (from about the same

time as the blocking of the apse?),15 and although they are

much damaged, several of the subjects can be seen to include

a mitred figure of a bishop or archbishop. Very likely, the

scenes form a unique cycle depicting a venerated archbishop

of Canterbury, such as St Dunstan, St Anselm (whose relics

were translated to St Anselm’s Chapel, immediately above,

probably in the 1140s), or St Thomas Becket himself. The

layout of the scenes in roundels with intervening foliage is

very characteristic of Romanesque and early Gothic vault pro-

grammes in England (other examples are found in the Ca-

thedrals of Ely, Norwich and Winchester),16 though it is paral-

leled - on a much grander scale - at Brunswick Cathedral

in the thirteenth century. Much conservation work and further

uncovering has been undertaken in recent years by the Ca-

thedral’s Wallpaintings Workshop in the nave, which also re-

tains various fragments of later medieval and post-Reforma-

tion wall painting.

Technique of the Paintings

Both the earlier and the later schemes of Romanesque paint-

ing in the chapel provide interesting evidence of preliminary

drawing techniques. The most striking examples are on the

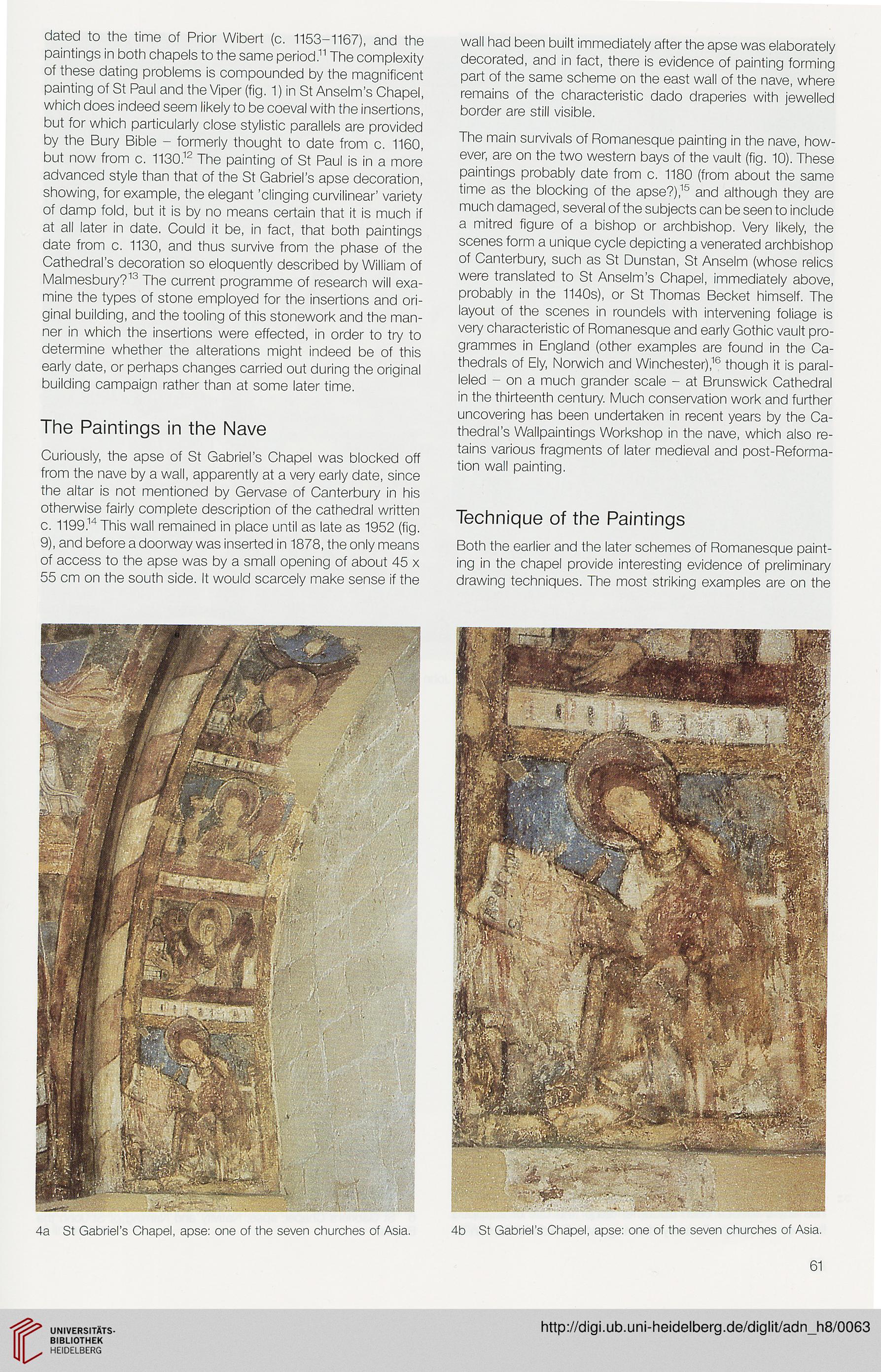

4a St Gabriel’s Chapel, apse: one of the seven churches of Asia.

4b St Gabriel’s Chapel, apse: one of the seven churches of Asia.

61

paintings in both chapels to the same period.11 The complexity

of these dating problems is compounded by the magnificent

painting of St Paul and the Viper (fig. 1) in St Anselm’s Chapel,

which does indeed seem likely to be coeval with the insertions,

but for which particularly close stylistic parallels are provided

by the Bury Bible - formerly thought to date from c. 1160,

but now from c. 1130.12 The painting of St Paul is in a more

advanced style than that of the St Gabriel’s apse decoration,

showing, for example, the elegant ’clinging curvilinear’ variety

of damp fold, but it is by no means certain that it is much if

at all later in date. Could it be, in fact, that both paintings

date from c. 1130, and thus survive from the phase of the

Cathedral’s decoration so eloquently described by William of

Malmesbury?13 The current programme of research will exa-

mine the types of stone employed for the insertions and ori-

ginal building, and the tooling of this stonework and the man-

ner in which the insertions were effected, in order to try to

determine whether the alterations might indeed be of this

early date, or perhaps changes carried out during the original

building campaign rather than at some later time.

The Paintings in the Nave

Curiously, the apse of St Gabriel’s Chapel was blocked off

from the nave by a wall, apparently at a very early date, since

the altar is not mentioned by Gervase of Canterbury in his

otherwise fairly complete description of the cathedral written

c. 1199.14This wall remained in place until as late as 1952 (fig.

9), and before a doorway was inserted in 1878, the only means

of access to the apse was by a small opening of about 45 x

55 cm on the south side. It would scarcely make sense if the

wall had been built immediately after the apse was elaborately

decorated, and in fact, there is evidence of painting forming

part of the same scheme on the east wall of the nave, where

remains of the characteristic dado draperies with jewelled

border are still visible.

The main survivals of Romanesque painting in the nave, how-

ever, are on the two western bays of the vault (fig. 10). These

paintings probably date from c. 1180 (from about the same

time as the blocking of the apse?),15 and although they are

much damaged, several of the subjects can be seen to include

a mitred figure of a bishop or archbishop. Very likely, the

scenes form a unique cycle depicting a venerated archbishop

of Canterbury, such as St Dunstan, St Anselm (whose relics

were translated to St Anselm’s Chapel, immediately above,

probably in the 1140s), or St Thomas Becket himself. The

layout of the scenes in roundels with intervening foliage is

very characteristic of Romanesque and early Gothic vault pro-

grammes in England (other examples are found in the Ca-

thedrals of Ely, Norwich and Winchester),16 though it is paral-

leled - on a much grander scale - at Brunswick Cathedral

in the thirteenth century. Much conservation work and further

uncovering has been undertaken in recent years by the Ca-

thedral’s Wallpaintings Workshop in the nave, which also re-

tains various fragments of later medieval and post-Reforma-

tion wall painting.

Technique of the Paintings

Both the earlier and the later schemes of Romanesque paint-

ing in the chapel provide interesting evidence of preliminary

drawing techniques. The most striking examples are on the

4a St Gabriel’s Chapel, apse: one of the seven churches of Asia.

4b St Gabriel’s Chapel, apse: one of the seven churches of Asia.

61