2U2 PUNCH, OR THE LONDON CHARIVARI. |November 13, 1858.

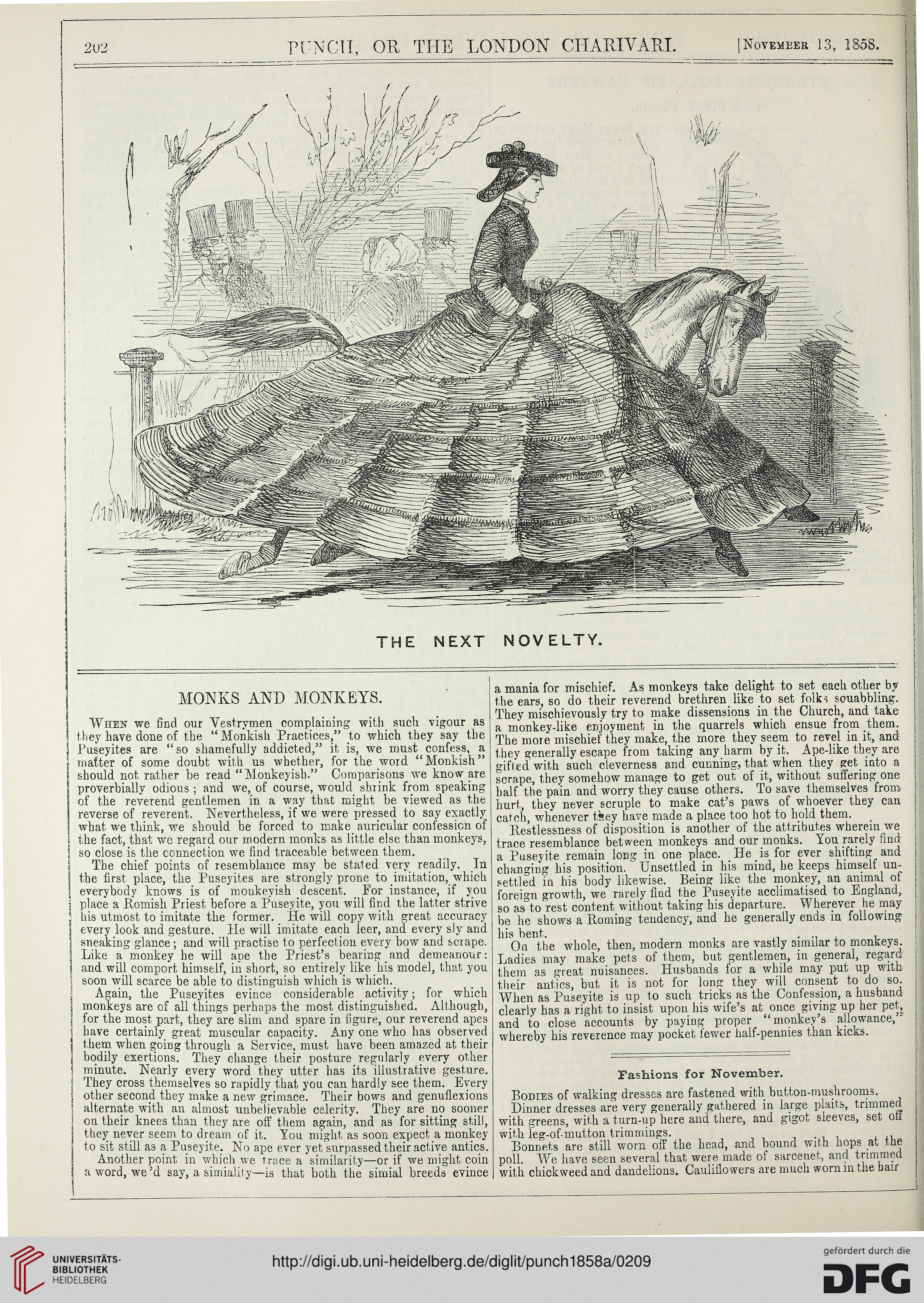

THE NEXT NOVELTY.

MONKS AND MONKEYS.

When we find our Vestrymen complaining with such vigour as

they have done of the "Monkish Practices," to which they say the

Puseyites are "so shamefully addicted," it is, we must confess, a

matter of some doubt with us whether, for the word "Monkish"

should not rather be read "Monkeyish." Comparisons we know are

proverbially odious ; and we, of course, would shrink from speaking

of the reverend gentlemen in a way that might be viewed as the

reverse of reverent. Nevertheless, if we were pressed to say exactly

what we think, we should be forced to make auricular confession of

the fact, that we regard our modern monks as little else than monkeys,

so close is the connection we find traceable between them.

The chief points of resemblauce may be stated very readily. In

the first place, the Puseyites are strongly prone to imitation, which

everybody knows is of monkeyish descent. For instance, if you

place a Bomish Priest before a Puseyite, you will find the latter strive

his utmost to imitate the former. He will copy with great accuracy

every look and gesture. He will imitate each leer, and every sly and

sneaking glance; and. will practise to perfection every bow and scrape.

Like a monkey he will ape the Priest's bearing and demeanour:

and will comport himself, in short, so entirely like his model, that you

soon will scarce be able to distinguish which is which.

Again, the Puseyites evince considerable activity; for which

I monkeys are of all things perhaps the most distinguished. Although,

I for the most part, they are slim and spare in figure, our reverend apes

have certainly great muscular capacity. Any one who has observed

them when going through a Service, must have been amazed at their

bodily exertions. They change their posture regularly every other

minute. Nearly every word they utter has its illustrative gesture.

; They cross themselves so rapidly that you can hardly see them. Every

other second they make a new grimace. Their bows and genuflexions

alternate with an almost unbelievable celerity. They are no sooner

on their knees than they are off them again, and as for sitting still,

they never seem to dream of it. You might as soon expect a monkey

to sit still as a Puseyite. No ape ever yet surpassed their active antics.

Another point in which we trace a similarity—or if we might coin

a word, we'd say, a simiality—is that both the simial breeds evince

a mania for mischief. As monkeys take delight to set each other by

the ears, so do their reverend brethren like to set folk^; souabbling.

They mischievously try to make dissensions in the Church, and take

a monkey-like enjoyment in the quarrels which ensue from them.

The moie mischief they make, the more they seem to revel in it, and

they generally escape from taking any harm by it. Ape-like they are

gifted with such cleverness and cunning, that when they get into a

scrape, they somehow manage to get out of it, without suffering one

half the pain and worry they cause others. To save themselves from

hurt, they never scruple to make cat's paws of whoever they can

catch, whenever t*ey have made a place too hot to hold them.

Restlessness of disposition is another of the attributes wherein we

trace resemblance between monkeys and our monks. You rarely find

a Puseyite remain long in one place. He is for ever shifting and j

changing his position. Unsettled in his mind, he keeps himself un-

settled in his body likewise. Being like the monkey, an animal of

foreign growth, we rarely find the Puseyite acclimatised to England,,

so as to rest content without taking his departure. Wherever he may

be lie shows a Poming tendency, and he generally ends in following

his bent.

On the whole, then, modern monks are vastly similar to monkeys.

Ladies may make pets of them, but gentlemen, in general, regard

them as great nuisances. Husbands for a while may put up with

their antics, but it is not for long they will consent to do so.

When as Puseyite is up to such tricks as the Confession, a husband

clearly has a right to insist upon his wife's at once giving up her pet,

and to close accounts by paying proper "monkey's allowance,"

whereby his reverence may pocket fewer half-pennies than kicks.

Fashions for November.

Bodies of walking dresses are fastened with button-mushrooms.

Dinner dresses are very generally gathered in large plaits, trimmed

with greens, with a turn-up here and there, and gigot sleeves, set off

with leg-of-mutton trimmings.

Bonnets are still worn off the head, and bound with hops at the

poll. We have seen several that were made of sarcenet, and trimmed

with chick weed and dandelions. Cauliflowers are much worn in the hair

THE NEXT NOVELTY.

MONKS AND MONKEYS.

When we find our Vestrymen complaining with such vigour as

they have done of the "Monkish Practices," to which they say the

Puseyites are "so shamefully addicted," it is, we must confess, a

matter of some doubt with us whether, for the word "Monkish"

should not rather be read "Monkeyish." Comparisons we know are

proverbially odious ; and we, of course, would shrink from speaking

of the reverend gentlemen in a way that might be viewed as the

reverse of reverent. Nevertheless, if we were pressed to say exactly

what we think, we should be forced to make auricular confession of

the fact, that we regard our modern monks as little else than monkeys,

so close is the connection we find traceable between them.

The chief points of resemblauce may be stated very readily. In

the first place, the Puseyites are strongly prone to imitation, which

everybody knows is of monkeyish descent. For instance, if you

place a Bomish Priest before a Puseyite, you will find the latter strive

his utmost to imitate the former. He will copy with great accuracy

every look and gesture. He will imitate each leer, and every sly and

sneaking glance; and. will practise to perfection every bow and scrape.

Like a monkey he will ape the Priest's bearing and demeanour:

and will comport himself, in short, so entirely like his model, that you

soon will scarce be able to distinguish which is which.

Again, the Puseyites evince considerable activity; for which

I monkeys are of all things perhaps the most distinguished. Although,

I for the most part, they are slim and spare in figure, our reverend apes

have certainly great muscular capacity. Any one who has observed

them when going through a Service, must have been amazed at their

bodily exertions. They change their posture regularly every other

minute. Nearly every word they utter has its illustrative gesture.

; They cross themselves so rapidly that you can hardly see them. Every

other second they make a new grimace. Their bows and genuflexions

alternate with an almost unbelievable celerity. They are no sooner

on their knees than they are off them again, and as for sitting still,

they never seem to dream of it. You might as soon expect a monkey

to sit still as a Puseyite. No ape ever yet surpassed their active antics.

Another point in which we trace a similarity—or if we might coin

a word, we'd say, a simiality—is that both the simial breeds evince

a mania for mischief. As monkeys take delight to set each other by

the ears, so do their reverend brethren like to set folk^; souabbling.

They mischievously try to make dissensions in the Church, and take

a monkey-like enjoyment in the quarrels which ensue from them.

The moie mischief they make, the more they seem to revel in it, and

they generally escape from taking any harm by it. Ape-like they are

gifted with such cleverness and cunning, that when they get into a

scrape, they somehow manage to get out of it, without suffering one

half the pain and worry they cause others. To save themselves from

hurt, they never scruple to make cat's paws of whoever they can

catch, whenever t*ey have made a place too hot to hold them.

Restlessness of disposition is another of the attributes wherein we

trace resemblance between monkeys and our monks. You rarely find

a Puseyite remain long in one place. He is for ever shifting and j

changing his position. Unsettled in his mind, he keeps himself un-

settled in his body likewise. Being like the monkey, an animal of

foreign growth, we rarely find the Puseyite acclimatised to England,,

so as to rest content without taking his departure. Wherever he may

be lie shows a Poming tendency, and he generally ends in following

his bent.

On the whole, then, modern monks are vastly similar to monkeys.

Ladies may make pets of them, but gentlemen, in general, regard

them as great nuisances. Husbands for a while may put up with

their antics, but it is not for long they will consent to do so.

When as Puseyite is up to such tricks as the Confession, a husband

clearly has a right to insist upon his wife's at once giving up her pet,

and to close accounts by paying proper "monkey's allowance,"

whereby his reverence may pocket fewer half-pennies than kicks.

Fashions for November.

Bodies of walking dresses are fastened with button-mushrooms.

Dinner dresses are very generally gathered in large plaits, trimmed

with greens, with a turn-up here and there, and gigot sleeves, set off

with leg-of-mutton trimmings.

Bonnets are still worn off the head, and bound with hops at the

poll. We have seen several that were made of sarcenet, and trimmed

with chick weed and dandelions. Cauliflowers are much worn in the hair

Werk/Gegenstand/Objekt

Titel

Titel/Objekt

The next novelty

Weitere Titel/Paralleltitel

Serientitel

Punch

Sachbegriff/Objekttyp

Inschrift/Wasserzeichen

Aufbewahrung/Standort

Aufbewahrungsort/Standort (GND)

Inv. Nr./Signatur

H 634-3 Folio

Objektbeschreibung

Maß-/Formatangaben

Auflage/Druckzustand

Werktitel/Werkverzeichnis

Herstellung/Entstehung

Entstehungsdatum

um 1858

Entstehungsdatum (normiert)

1853 - 1863

Entstehungsort (GND)

Auftrag

Publikation

Fund/Ausgrabung

Provenienz

Restaurierung

Sammlung Eingang

Ausstellung

Bearbeitung/Umgestaltung

Thema/Bildinhalt

Thema/Bildinhalt (GND)

Literaturangabe

Rechte am Objekt

Aufnahmen/Reproduktionen

Künstler/Urheber (GND)

Reproduktionstyp

Digitales Bild

Rechtsstatus

Public Domain Mark 1.0

Creditline

Punch, 35.1858, November 13, 1858, S. 202

Beziehungen

Erschließung

Lizenz

CC0 1.0 Public Domain Dedication

Rechteinhaber

Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg