662

Francis Ames-Lewis

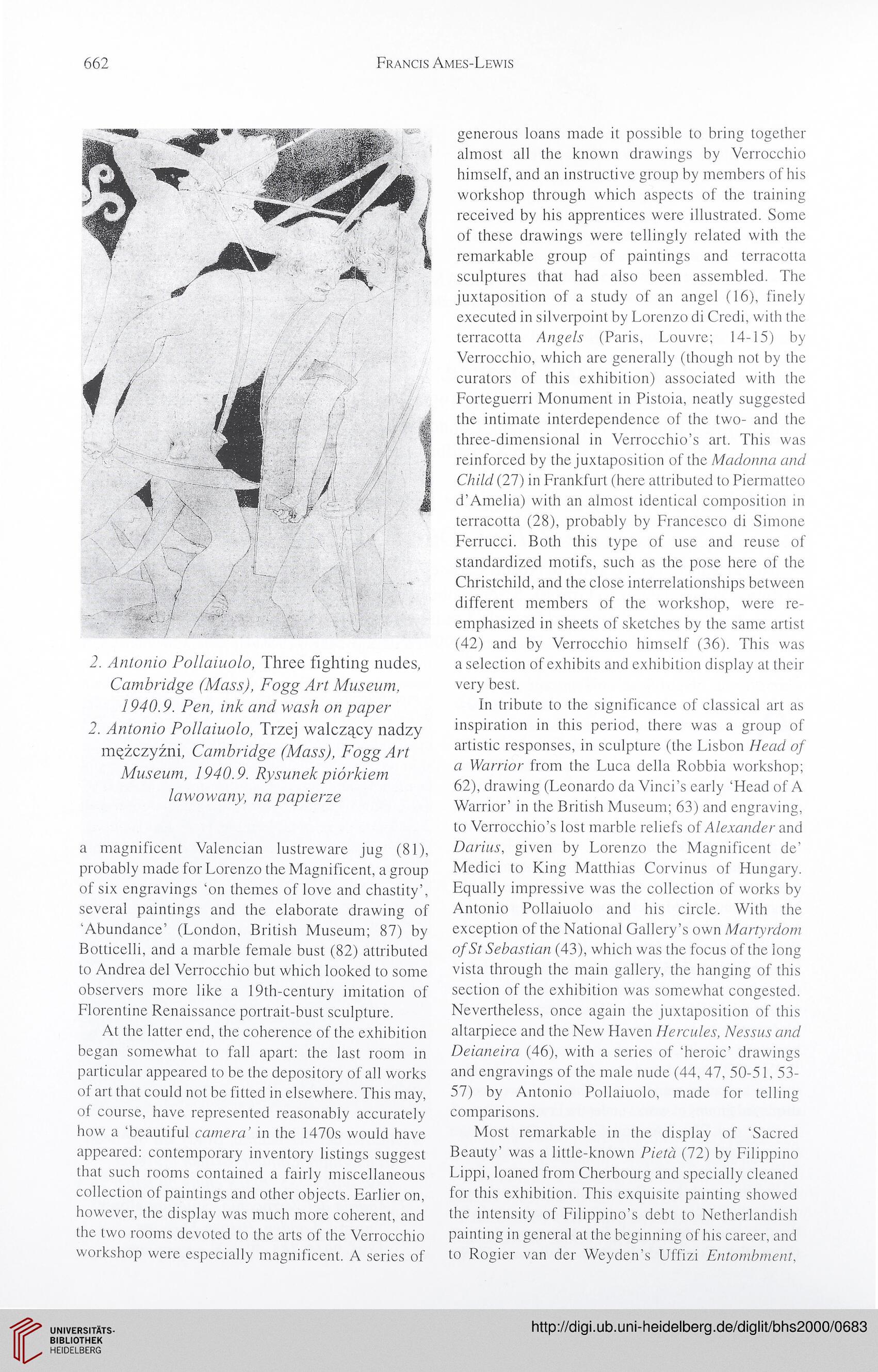

2. Antonio Pollaiuolo, Three fighting nudes,

Cambridge (Mass), Fogg Art Museum,

1940.9. Pen, ink and wash on paper

2. Antonio Pollaiuolo, Trzej walczący nadzy

mężczyźni, Cambridge (Mass), Fogg Art

Museum, 1940.9. Rysunek piórkiem

lawowany, na papierze

a magnificent Valencian lustreware jug (81),

probably madę for Lorenzo the Magnificent, a group

of six engravings ‘on themes of love and chastity’,

several paintings and the elaborate drawing of

‘Abundance’ (London, British Museum; 87) by

Botticelli, and a marble female bust (82) attributed

to Andrea del Verrocchio but which looked to some

observers morę like a 19th-century imitation of

Florentine Renaissance portrait-bust sculpture.

At the latter end, the coherence of the exhibition

began somewhat to fali apart; the last room in

particular appeared to be the depository of all works

of art that could not be fitted in elsewhere. This may,

of course, have represemed reasonably accurately

how a ‘beautiful camera’ in the 1470s would have

appeared: contemporary inventory listings suggest

that such rooms contained a fairly miscellaneous

collection of paintings and other objects. Earlier on,

however, the display was much morę cohercnt, and

the two rooms devoted to the arts of the Verrocchio

workshop were especially magnificent. A series of

generous loans madę it possible to bring together

almost all the known drawings by Verrocchio

himself, and an instructive group by members of his

workshop through which aspects of the training

received by his apprentices were illustrated. Some

of these drawings were tellingly related with the

remarkable group of paintings and terracotta

sculptures that had also been assembled. The

juxtaposition of a study of an angel (16), finely

executed in silverpoint by Lorenzo di Credi, with the

terracotta Angels (Paris, Louvre; 14-15) by

Verrocchio, which are generałly (though not by the

curators of this exhibition) associated with the

Forteguerri Monument in Pistoia, neatly suggested

the intimate interdependence of the two- and the

three-dimensional in Verrocchio’s art. This was

reinforced by the juxtaposition of the Madonna and

Child (27) in Frankfurt (here attributed to Piermatteo

d’Amelia) with an almost identical composition in

terracotta (28), probably by Francesco di Simone

Ferrucci. Both this type of use and reuse of

standardized motifs, such as the pose here of the

Christchild, and the close interrelationships between

different members of the workshop, were re-

emphasized in shcets of sketches by the same artist

(42) and by Verrocchio himself (36). This was

a selection of exhibits and exhibition display at their

very best.

In tribute to the significance of classical art as

inspiration in this period, there was a group of

artistic responses, in sculpture (the Lisbon Head of

a Warrior from the Luca della Robbia workshop;

62), drawing (Leonardo da Vinci’s early ‘Head of A

Warrior’ in the British Museum; 63) and engraving,

to Verrocchio’s lost marble reliefs of Alexander and

Darius, given by Lorenzo the Magnificent de’

Medici to King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary.

Eąually impressive was the collection of works by

Antonio Pollaiuolo and his circle. With the

exception of the National Gallery’s own Martyrdom

ofSt Sebastian (43), which was the focus of the long

vista through the main gallery, the hanging of this

section of the exhibition was somewhat congested.

Nevertheless, once again the juxtaposition of this

altarpiece and the New Haven Hercules, Nessus and

Deianeira (46), with a series of ‘heroic’ drawings

and engravings of the małe nudę (44, 47, 50-51,53-

57) by Antonio Pollaiuolo, madę for telling

comparisons.

Most remarkable in the display of ‘Sacred

Beauty’ was a little-known Pieta (72) by Filippino

Lippi, loaned from Cherbourg and specially cleaned

for this exhibition. This exquisite painting showed

the intensity of Filippino’s debt to Netherlandish

painting in generał at the beginning of his career, and

to Rogier van der Weyden’s Uffizi Entombment,

Francis Ames-Lewis

2. Antonio Pollaiuolo, Three fighting nudes,

Cambridge (Mass), Fogg Art Museum,

1940.9. Pen, ink and wash on paper

2. Antonio Pollaiuolo, Trzej walczący nadzy

mężczyźni, Cambridge (Mass), Fogg Art

Museum, 1940.9. Rysunek piórkiem

lawowany, na papierze

a magnificent Valencian lustreware jug (81),

probably madę for Lorenzo the Magnificent, a group

of six engravings ‘on themes of love and chastity’,

several paintings and the elaborate drawing of

‘Abundance’ (London, British Museum; 87) by

Botticelli, and a marble female bust (82) attributed

to Andrea del Verrocchio but which looked to some

observers morę like a 19th-century imitation of

Florentine Renaissance portrait-bust sculpture.

At the latter end, the coherence of the exhibition

began somewhat to fali apart; the last room in

particular appeared to be the depository of all works

of art that could not be fitted in elsewhere. This may,

of course, have represemed reasonably accurately

how a ‘beautiful camera’ in the 1470s would have

appeared: contemporary inventory listings suggest

that such rooms contained a fairly miscellaneous

collection of paintings and other objects. Earlier on,

however, the display was much morę cohercnt, and

the two rooms devoted to the arts of the Verrocchio

workshop were especially magnificent. A series of

generous loans madę it possible to bring together

almost all the known drawings by Verrocchio

himself, and an instructive group by members of his

workshop through which aspects of the training

received by his apprentices were illustrated. Some

of these drawings were tellingly related with the

remarkable group of paintings and terracotta

sculptures that had also been assembled. The

juxtaposition of a study of an angel (16), finely

executed in silverpoint by Lorenzo di Credi, with the

terracotta Angels (Paris, Louvre; 14-15) by

Verrocchio, which are generałly (though not by the

curators of this exhibition) associated with the

Forteguerri Monument in Pistoia, neatly suggested

the intimate interdependence of the two- and the

three-dimensional in Verrocchio’s art. This was

reinforced by the juxtaposition of the Madonna and

Child (27) in Frankfurt (here attributed to Piermatteo

d’Amelia) with an almost identical composition in

terracotta (28), probably by Francesco di Simone

Ferrucci. Both this type of use and reuse of

standardized motifs, such as the pose here of the

Christchild, and the close interrelationships between

different members of the workshop, were re-

emphasized in shcets of sketches by the same artist

(42) and by Verrocchio himself (36). This was

a selection of exhibits and exhibition display at their

very best.

In tribute to the significance of classical art as

inspiration in this period, there was a group of

artistic responses, in sculpture (the Lisbon Head of

a Warrior from the Luca della Robbia workshop;

62), drawing (Leonardo da Vinci’s early ‘Head of A

Warrior’ in the British Museum; 63) and engraving,

to Verrocchio’s lost marble reliefs of Alexander and

Darius, given by Lorenzo the Magnificent de’

Medici to King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary.

Eąually impressive was the collection of works by

Antonio Pollaiuolo and his circle. With the

exception of the National Gallery’s own Martyrdom

ofSt Sebastian (43), which was the focus of the long

vista through the main gallery, the hanging of this

section of the exhibition was somewhat congested.

Nevertheless, once again the juxtaposition of this

altarpiece and the New Haven Hercules, Nessus and

Deianeira (46), with a series of ‘heroic’ drawings

and engravings of the małe nudę (44, 47, 50-51,53-

57) by Antonio Pollaiuolo, madę for telling

comparisons.

Most remarkable in the display of ‘Sacred

Beauty’ was a little-known Pieta (72) by Filippino

Lippi, loaned from Cherbourg and specially cleaned

for this exhibition. This exquisite painting showed

the intensity of Filippino’s debt to Netherlandish

painting in generał at the beginning of his career, and

to Rogier van der Weyden’s Uffizi Entombment,