Recenzje

663

which was then the altarpiece for the chapel at

Lorenzo de’ Medici’s villa at Careggi, in particular.

Filippino’s debt to northern art, shown also in the

landscapes of his early Adoration of the Magi

(London, National Gallery; 69) and in the landscape

vignette copied from Jan van Eyck that he supplied

to the Adoration (68), also in the National Gallery,

London, on which he collaborated with Botticelli, is

an example of the generał interest shown by

Florentine artists in the 1470s in Netherlandish art.

The parallel Yenetian debts to northern art were the

primary focus of the Palazzo Grassi exhibition, but

this was an aspect of Florentine art at the time that

was neglected in the London exhibition. This lack

was emphasised by the noteworthy absence of any

works by the young Domenico Ghirlandaio, whose

debt in his Ognissanti St Jerome to a van Eyckian

prototype (very probably the St Jerome now in

Detroit, included in the Palazzo Grassi exhibition) is

very evident. Despite this lacuna, however, this was

a fine exhibition, which unusually (for the National

Gallery) but necessarily brought together works in

many media, illustrated all facets of ‘the art of the

1470s’, one of the most enterprising and inventive

decades in early-Renaissance Florentine art.

The huge exhibition on the theme of U Rinascimento

a Venezia e la pittura del Nord ‘ai tempi di Bellini,

Diirer, Tiziano’, on display at the Palazzo Grassi,

Venice was principally of paintings, with a few smali

rooms devoted to drawings and engravings. There

were morę than two hundred works on display, and it

is clearly not possible to do justice here to all the

effective juxtapositions that were madę. The

exhibition covered a much wider chronological span

than the London exhibition, and sought to

demonstrate the interdependence of Venice and its

neighbours - especially its trading partners north of

the Alps - throughout the Renaissance period.

However, it became gradually less coherent as it

moved further into the 16th century, with various

paintings that appeared to have little morę to do than

fili spaces on the walls. This review will therefore

concentrate on the earlier rooms, in which paintings

belonging to the same era as those in the London

exhibition were displayed.

The first work to meet the visitor’s eyes was the

huge triptych on canvas of the Madonna and Child

with the Church Fathers, painted by Giovanni

d’ Alemagna and Antonio Vivarini originally for the

Scuola della Carita, which looked decidedly

cramped in its smali space. Nevertheless, it madę the

point that as early as the 1440s there was an

important German painter working in Venice, even

if (as is suggested in the catalogue entry) his

contribution to the workshop output was principally

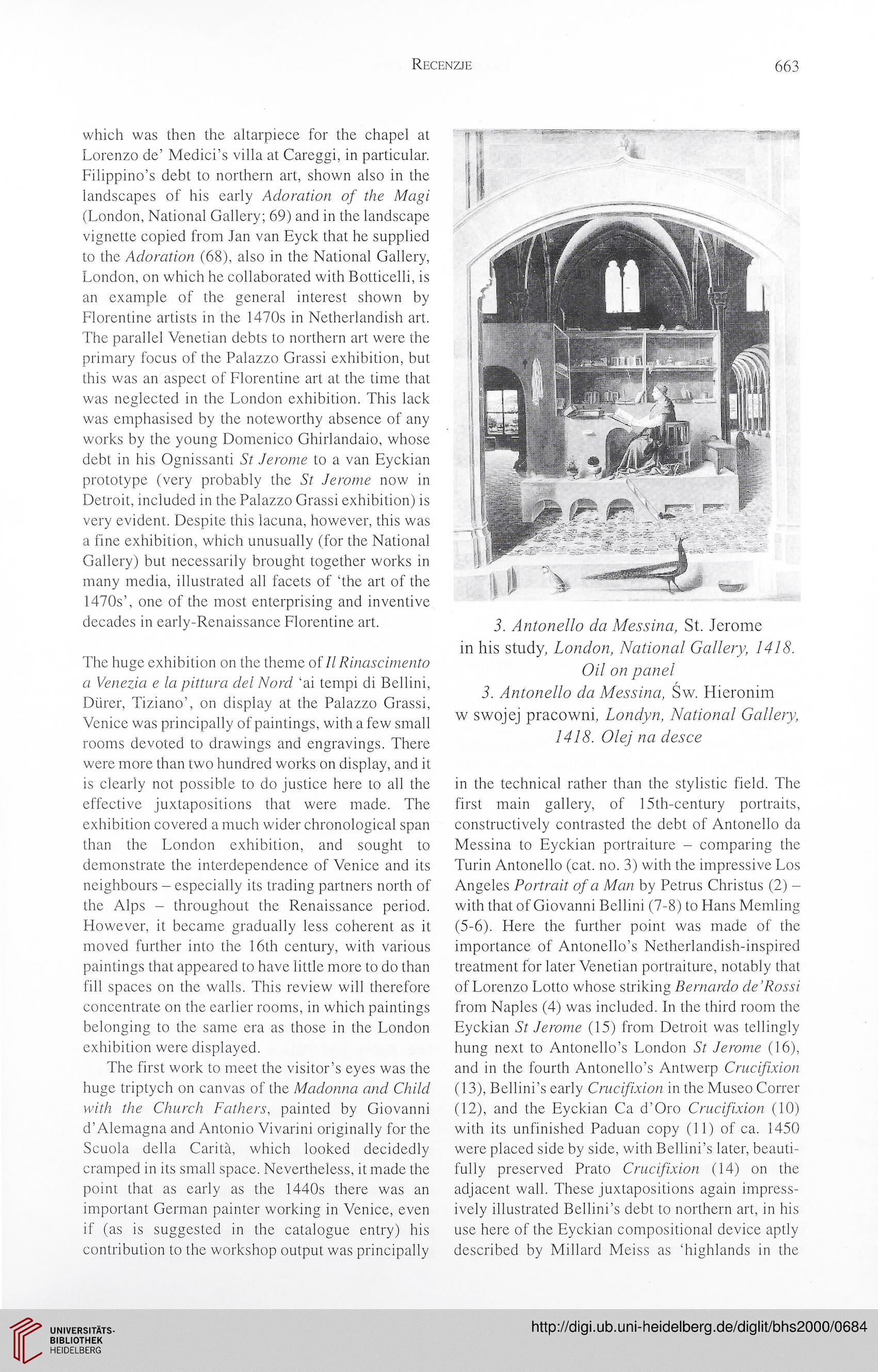

3. Antonello da Messina, St. Jerome

in his study, London, National Gallery, 1418.

Oil on panel

3. Antonello da Messina, Św. Hieronim

w swojej pracowni, Londyn, National Gallery,

1418. Olej na desce

in the technical rather than the stylistic field. The

first main gallery, of 15th-century portraits,

constructively contrasted the debt of Antonello da

Messina to Eyckian portraiture - comparing the

Turin Antonello (cat. no. 3) with the impressive Los

Angeles Portrait of a Man by Petrus Christus (2) -

with that of Giovanni Bellini (7-8) to Hans Memling

(5-6). Here the further point was madę of the

importance of Antonello’s Netherlandish-inspired

treatment for later Venetian portraiture, notably that

of Lorenzo Lotto whose striking Bernarda de’Rossi

from Naples (4) was included. In the third room the

Eyckian St Jerome (15) from Detroit was tellingly

hung next to Antonello’s London St Jerome (16),

and in the fourth Antonello’s Antwerp Crucifixion

(13), Bellini’s early Crucifixion in the Museo Correr

(12), and the Eyckian Ca d’Oro Crucifixion (10)

with its unfinished Paduan copy (11) of ca. 1450

were placed side by side, with Bellini’s later, beauti-

fully preserved Prato Crucifixion (14) on the

adjacent wali. These juxtapositions again impress-

ively illustrated Bellini’s debt to northern art, in his

use here of the Eyckian compositional device aptly

described by Miliard Meiss as ‘highlands in the

663

which was then the altarpiece for the chapel at

Lorenzo de’ Medici’s villa at Careggi, in particular.

Filippino’s debt to northern art, shown also in the

landscapes of his early Adoration of the Magi

(London, National Gallery; 69) and in the landscape

vignette copied from Jan van Eyck that he supplied

to the Adoration (68), also in the National Gallery,

London, on which he collaborated with Botticelli, is

an example of the generał interest shown by

Florentine artists in the 1470s in Netherlandish art.

The parallel Yenetian debts to northern art were the

primary focus of the Palazzo Grassi exhibition, but

this was an aspect of Florentine art at the time that

was neglected in the London exhibition. This lack

was emphasised by the noteworthy absence of any

works by the young Domenico Ghirlandaio, whose

debt in his Ognissanti St Jerome to a van Eyckian

prototype (very probably the St Jerome now in

Detroit, included in the Palazzo Grassi exhibition) is

very evident. Despite this lacuna, however, this was

a fine exhibition, which unusually (for the National

Gallery) but necessarily brought together works in

many media, illustrated all facets of ‘the art of the

1470s’, one of the most enterprising and inventive

decades in early-Renaissance Florentine art.

The huge exhibition on the theme of U Rinascimento

a Venezia e la pittura del Nord ‘ai tempi di Bellini,

Diirer, Tiziano’, on display at the Palazzo Grassi,

Venice was principally of paintings, with a few smali

rooms devoted to drawings and engravings. There

were morę than two hundred works on display, and it

is clearly not possible to do justice here to all the

effective juxtapositions that were madę. The

exhibition covered a much wider chronological span

than the London exhibition, and sought to

demonstrate the interdependence of Venice and its

neighbours - especially its trading partners north of

the Alps - throughout the Renaissance period.

However, it became gradually less coherent as it

moved further into the 16th century, with various

paintings that appeared to have little morę to do than

fili spaces on the walls. This review will therefore

concentrate on the earlier rooms, in which paintings

belonging to the same era as those in the London

exhibition were displayed.

The first work to meet the visitor’s eyes was the

huge triptych on canvas of the Madonna and Child

with the Church Fathers, painted by Giovanni

d’ Alemagna and Antonio Vivarini originally for the

Scuola della Carita, which looked decidedly

cramped in its smali space. Nevertheless, it madę the

point that as early as the 1440s there was an

important German painter working in Venice, even

if (as is suggested in the catalogue entry) his

contribution to the workshop output was principally

3. Antonello da Messina, St. Jerome

in his study, London, National Gallery, 1418.

Oil on panel

3. Antonello da Messina, Św. Hieronim

w swojej pracowni, Londyn, National Gallery,

1418. Olej na desce

in the technical rather than the stylistic field. The

first main gallery, of 15th-century portraits,

constructively contrasted the debt of Antonello da

Messina to Eyckian portraiture - comparing the

Turin Antonello (cat. no. 3) with the impressive Los

Angeles Portrait of a Man by Petrus Christus (2) -

with that of Giovanni Bellini (7-8) to Hans Memling

(5-6). Here the further point was madę of the

importance of Antonello’s Netherlandish-inspired

treatment for later Venetian portraiture, notably that

of Lorenzo Lotto whose striking Bernarda de’Rossi

from Naples (4) was included. In the third room the

Eyckian St Jerome (15) from Detroit was tellingly

hung next to Antonello’s London St Jerome (16),

and in the fourth Antonello’s Antwerp Crucifixion

(13), Bellini’s early Crucifixion in the Museo Correr

(12), and the Eyckian Ca d’Oro Crucifixion (10)

with its unfinished Paduan copy (11) of ca. 1450

were placed side by side, with Bellini’s later, beauti-

fully preserved Prato Crucifixion (14) on the

adjacent wali. These juxtapositions again impress-

ively illustrated Bellini’s debt to northern art, in his

use here of the Eyckian compositional device aptly

described by Miliard Meiss as ‘highlands in the