fine work by an unadvertised man be hung in an

obscure gallery, or in a bad roorn or bad place at

the Academy, iet us say, the betting is a hundred to

one that nearly every critic wiil pass it by unnoticed.

A knowledge of these elementary facts, and the

repugnance a sincere critic must feei increasingly

to the business of art criticism as a business, with

all its pedantry and superfrne insincerity, tends, as

years advance, to render him inarticulate; inarticu-

iate, that is to say, to this extent: he is more

and more inciined to accept or reject the art of his

day and generation without comment, or if with

comment, with comment of the kind the connois-

seur, dealer, and amateur—the modest amateur, be

it understood—empioy. Either a work of art is

good or it is bad ; so far as the real art-Iover is

concerned, art must be very good not to be bad.

He cares nothing at all for your middling per-

formance, nothing at all for

a picture—to confine these

remarks to pictures, though

of course, the critic, using

the word in its highest sense,

of any kind of artistic,

musical or literary work is

in a like case—which does

not possess in the flrst

instance two essential

qualities. It must have in-

dividuality; that is to say, it

must be expressive of a

powerful and distinct per-

sonality; it must have style,

to put it another way: and

it must be executed with

consummate technical

skill. In other words, the

man behind the picture

must be sharply differen-

tiated from other men,

and that difference must

take the form of accent-

uated power, accentuated

virility; a remarkable ap-

preciation of what is

essentially beautiful, and

a perfected command

over the technicalities of

his craft. To say this is

not merely to say that the

great painter must be a

fine colourist and draughts-

man, though the general

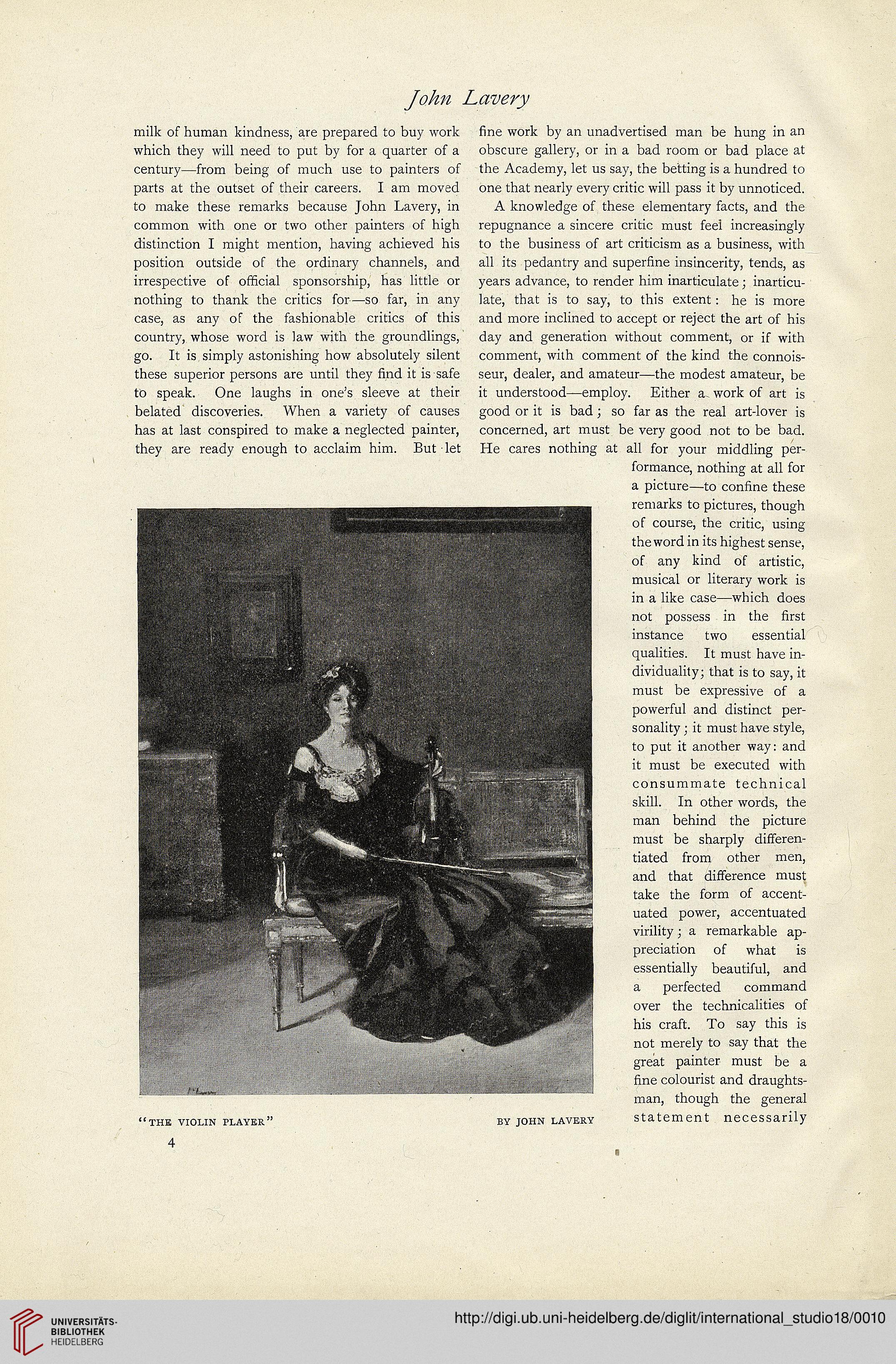

"THE vionN PLAYER" BY joHN LAVERY statement necessarily

milk of human kindness, are prepared to buy work

which they will need to put by for a quarter of a

century—from being of much use to painters of

parts at the outset of their careers. I am moved

to make these remarks because John Lavery, in

common with one or two other painters of high

distinction I might mention, having achieved his

position outside of the ordinary channels, and

irrespective of ofBcial sponsorship, has little or

nothing to thank the critics for—so far, in any

case, as any of the fashionable critics of this

country, whose word is law with the groundlings,

go. It is simply astonishing how absolutely silent

these superior persons are until they find it is safe

to speak. One laughs in one's sleeve at their

belated discoveries. When a variety of causes

has at last conspired to make a neglected painter,

they are ready enough to acclaim him. But let

4