/72<3?3<372 /%*/??/<3/ //

historical, and arch<eologicai interest, has attracted

so little attention from European This

is the more unfortunate because the destructive

agencies which are always at work in India are

continually narrowing the possibilities of investiga-

tion. In India itself

the very existence of

an indigenous school

of hne art is hardly

recognised, but appre-

ciation of the unique

artistic resources of the

empire has never been

a prominent virtue

either of the Anglo-

Indian administration

or of Indian patrons

of art. The earliest of

the existing examples

of Indian pictorial art

are the well - known

fresco paintings in the

Buddhist cave-temples

at Ajunta, in the Bom-

bay Presidency, which

date from the sixth

century. Though they

are the only extant ex-

amples of this period,

they are sufhcient to

show that the Indian

painter, when emanci-

pated from the restraint

imposed by the rigid

formalism of Hindu

artistic canons and

from the restrictions oi Mahomedan bigotry, can

interpret and enjoy to the full the inhnite poetical

suggestions of Indian life and Indian nature.

The painting of that period, besides being

strongly impressed by the humanising influence

of the teachings of Gautama, was greatly affected

by the artistic traditions of Greece, intro-

duced by the followers of Alexander's army

who settled in Northern India. When there

came the great religious revulsion which re-

stored the power of Hinduism throughout the

greater part of India, some of the Buddhist monks

who fled through the passes of the Himalayas into

Tibet and China brought their religion and their

art into Japan. This is the explanation of the

existence at the present day in some of the oldest

temples of Japan of paintings, treasured as the

most precious relics and rarely shown to Europeans,

26

which closely resemble the Grteco-Buddhist art

of India.

So the school of Ajunta carried its nature-

loving traditions into the congenial atmosphere

of far-off Japan, among a people whose artistic

sympathies were en-

tirely in the same direc-

tion. With the almost

total annihilation of the

Buddhist religion this

remarkable school of

painting became ex-

tinct in India. In the

Hindu caste system the

profession of a painter

ranks among the lowest

of all the artistic crafts.

For temple decoration

the Brahmin priesthood

always preferred the art

of the sculptor. The

scruples which kept the

low-caste painters out

of the temples also

prevented their em-

ployment in embellish-

ing the sacred writings

of the Hindus; so

after the disappearance

of the Buddhists there

is an interval of about

nine centuries before

painting as a hne art

took root again in

India. The Moguls

re-introduced fresco

painting, and brought with them Persian artists

to illuminate and illustrate their historical

writings, their classic literature, and their sacred

manuscripts. Down to the time of Akbar the

Great, or about the middle of the sixteenth

century, the works of these Persian painters fol-

lowed entirely the traditions of pure Persian art,

and bore little trace of their Indian environment.

Saracenic art, which was established in Northern

India, was very largely inHuenced by the strict

letter of the Mahomedan precept, which forbade

the artistic representation of nearly all living crea-

tures, including humanity. Akbar, who took charge

of the spiritual as well as the temporal welfare of

his subjects, perceived with his keen artistic instinct

how such a restriction fettered all higher artistic

inspiration, and promptly swept the restriction

away. With the whole wide held of Nature thus

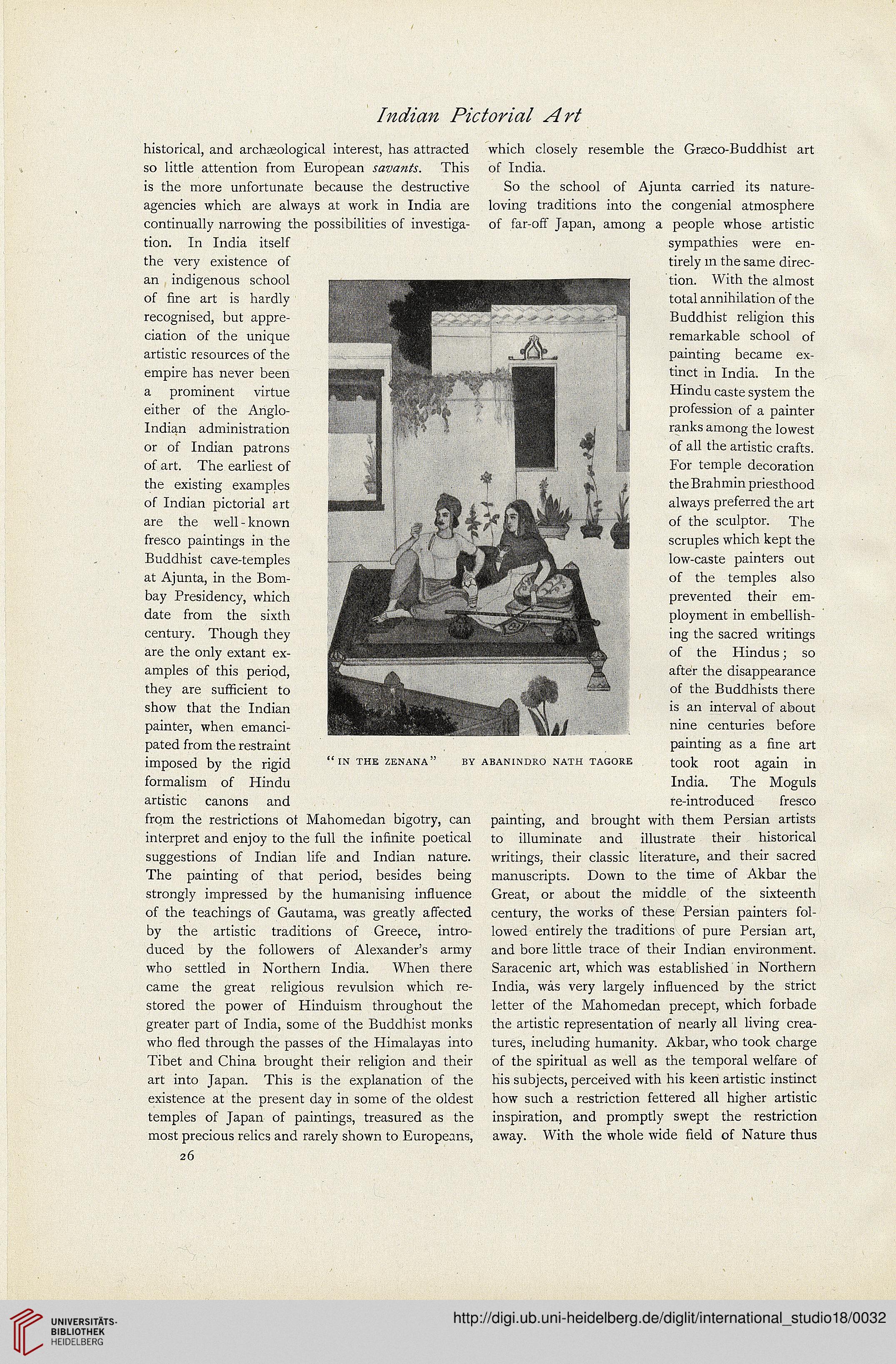

"tN THE ZENANA" liY ABANINDRO NATH TAGORE

historical, and arch<eologicai interest, has attracted

so little attention from European This

is the more unfortunate because the destructive

agencies which are always at work in India are

continually narrowing the possibilities of investiga-

tion. In India itself

the very existence of

an indigenous school

of hne art is hardly

recognised, but appre-

ciation of the unique

artistic resources of the

empire has never been

a prominent virtue

either of the Anglo-

Indian administration

or of Indian patrons

of art. The earliest of

the existing examples

of Indian pictorial art

are the well - known

fresco paintings in the

Buddhist cave-temples

at Ajunta, in the Bom-

bay Presidency, which

date from the sixth

century. Though they

are the only extant ex-

amples of this period,

they are sufhcient to

show that the Indian

painter, when emanci-

pated from the restraint

imposed by the rigid

formalism of Hindu

artistic canons and

from the restrictions oi Mahomedan bigotry, can

interpret and enjoy to the full the inhnite poetical

suggestions of Indian life and Indian nature.

The painting of that period, besides being

strongly impressed by the humanising influence

of the teachings of Gautama, was greatly affected

by the artistic traditions of Greece, intro-

duced by the followers of Alexander's army

who settled in Northern India. When there

came the great religious revulsion which re-

stored the power of Hinduism throughout the

greater part of India, some of the Buddhist monks

who fled through the passes of the Himalayas into

Tibet and China brought their religion and their

art into Japan. This is the explanation of the

existence at the present day in some of the oldest

temples of Japan of paintings, treasured as the

most precious relics and rarely shown to Europeans,

26

which closely resemble the Grteco-Buddhist art

of India.

So the school of Ajunta carried its nature-

loving traditions into the congenial atmosphere

of far-off Japan, among a people whose artistic

sympathies were en-

tirely in the same direc-

tion. With the almost

total annihilation of the

Buddhist religion this

remarkable school of

painting became ex-

tinct in India. In the

Hindu caste system the

profession of a painter

ranks among the lowest

of all the artistic crafts.

For temple decoration

the Brahmin priesthood

always preferred the art

of the sculptor. The

scruples which kept the

low-caste painters out

of the temples also

prevented their em-

ployment in embellish-

ing the sacred writings

of the Hindus; so

after the disappearance

of the Buddhists there

is an interval of about

nine centuries before

painting as a hne art

took root again in

India. The Moguls

re-introduced fresco

painting, and brought with them Persian artists

to illuminate and illustrate their historical

writings, their classic literature, and their sacred

manuscripts. Down to the time of Akbar the

Great, or about the middle of the sixteenth

century, the works of these Persian painters fol-

lowed entirely the traditions of pure Persian art,

and bore little trace of their Indian environment.

Saracenic art, which was established in Northern

India, was very largely inHuenced by the strict

letter of the Mahomedan precept, which forbade

the artistic representation of nearly all living crea-

tures, including humanity. Akbar, who took charge

of the spiritual as well as the temporal welfare of

his subjects, perceived with his keen artistic instinct

how such a restriction fettered all higher artistic

inspiration, and promptly swept the restriction

away. With the whole wide held of Nature thus

"tN THE ZENANA" liY ABANINDRO NATH TAGORE