restored to them, the Court artists were free to

exercise their talents under the most favourable

auspices.

Under these stimulating conditions a new and

characteristicahy Ind!an school of pictorial art

began to graft itseif upon

the traditions imported

from Persia. The early

work of Akbar's reign

follows to a great extent

the archaic and highiy

conventionalised style of

the old Persian schooi,

but towards the end of

his reign thegreatruier's

genius had impressed it-

seif upon the art in which

he took so eniightened

an interest. The new

school was realistic in

the sense that it went

direct to nature for in-

spiration, but it did not,

iike some modern Euro-

pean realists, Hing artistic

tradition to the winds.

The Mcgul artists added

to the wonderful tech-

nical qualities and the

strong decorative in-

stinct of the Persian

schooi a greater anato-

mical precision in the

drawing of the hgure,

and an almost Holbein-

esque power of dehneat-

ing character in their portraiture. Under Jehangir,

the son and successor of Akbar, who inherited

all his father's taste, these new ideas continued to

bear fruit, and gave fair promise of the deveiop-

ment of a reahy great school of Indian painting.

Though Shah Jehan's artistic interests inciined

more to architecture than to painting, there is

nothing to show that he activeiy discouraged the

artists whom his father and grandfather had

patronised so iiberaily. But the bigotry of

Aurungzebe, the successor of Shah Jehan, wrecked

the fair prospects of the Mogui schooi of painting.

He enforced again the strict observance of the

Mahomedan law, banished from his Court the

artists who had impiousiy disregarded it, and muti-

iated or defaced ail the sculpture and paintings

which were deemed to be irreiigious.

This was the beginning of a period which has

been most disastrous to aH art progress in India.

The traditions of the Mogui school were continued

by artists who settled at Deihi, Jeypore, Lahore,

Mysore, and elsewhere; but painting as a Hne art

never regained the position and dignity it enjoyed

under Akbar and

Jehangir. Nevertheless,

during the short period

of their prosperity, and

even afterwards under

the successive blight of

Mahomedan bigotry,

political anarchy, and

British philistinism, the

Mogul artists produced

a record of Indian life,

manners, and history

which has been almost

entirely ignored, even

by those who are in-

terested in the art and

archteology of the great

Indian empire.

This brief sketch of

the history of painting

in India is necessary for

the right understanding

of the work of Mr.

Abanindro Nath Ta-

gore, of Calcutta, which

I now introduce to the

readers ofTHE Si'UDio.

Mr. A. N. Tagore comes

of an old Indian family

distinguished for its

literary, musical, and

artistic talent. One of his brothers, Mr. Robindro

Nath Tagore, has won a great reputation as a

Bengali poet and dramatist. Another near relative,

Sir Sourindro Mohun Tagore, Mus. Doc., has

earned a European name as the chief authority on

Indian music.

It speaks much for Mr. Tagore's genuine artistic

instinct that he has not allowed his talent to be

misled by the many snares which beset the path of

the Indian art student. It is often made a reproach

against the present generation of Indians that so

few have shown any originality in artistic or literary

thought. The reproach should rather be levelled

against our educational systern; for if the system had

been expressly contrived for the stiHing and crush-

ing out of all originality, nothing could have been

better adapted for the purpose than what is called

" higher education " in India. Original artistic

29

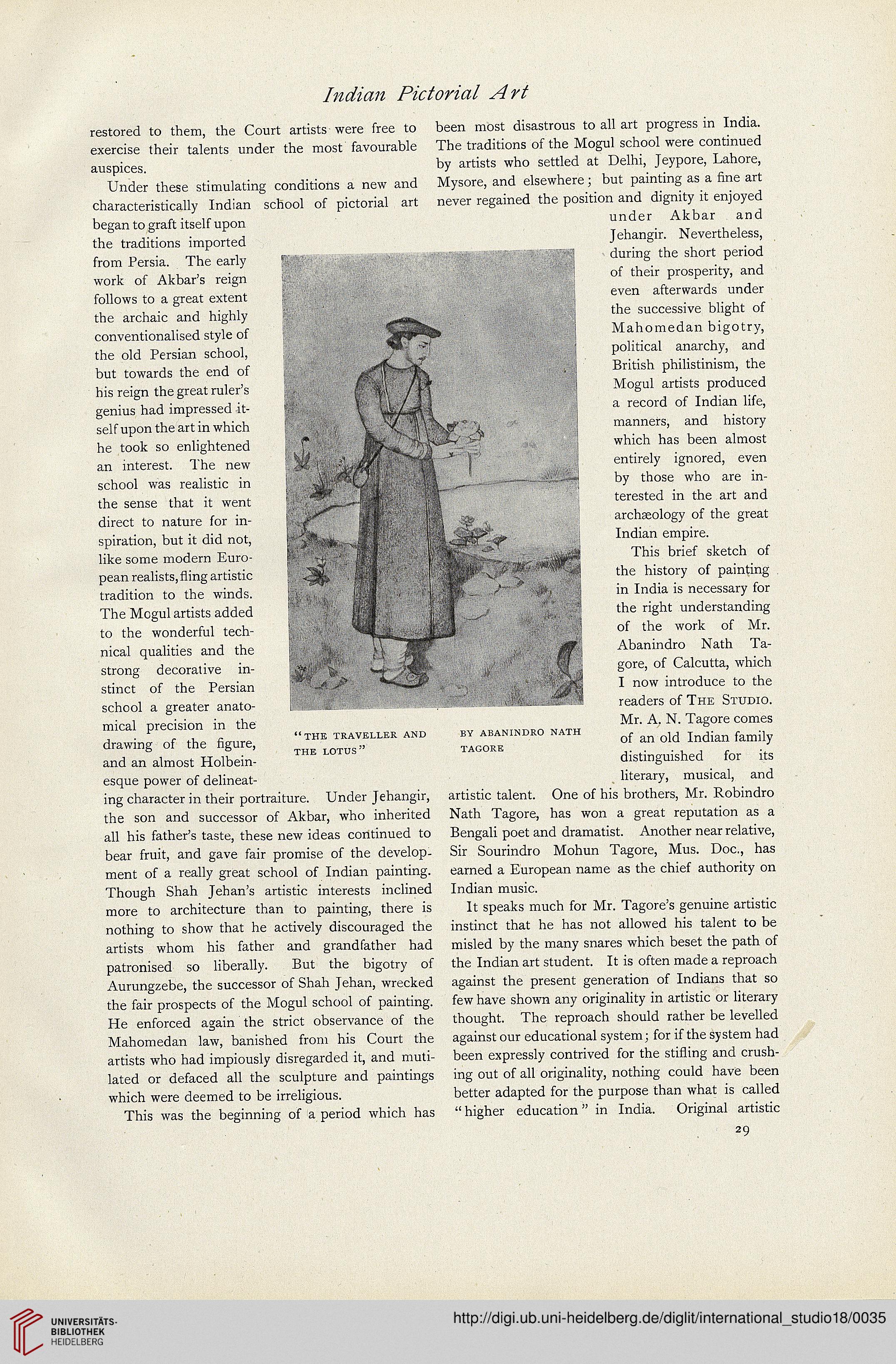

"THE TRAVELLER AND

THE LOTUS"

BY ABANINDRO NATH

TAGORE