yi%6W3t7.y

Thames sketches ittustrated in this articie, and the

fact wiii be borne in upon you. Monet, one feeis

quite sure, after seeing the out-door impressions

just named, wiii weicome Girtin as a precursor.

Girtin's tones, as I have said, are quiet; they make

no attempt to vie with the wondrous grey briiiiancy

of Nature's hues; they translate, they interpret,

theydo not imitate; but the effects produced by

their deiightfui harmonies in a iow key are yet

quite wonderfuliy real at their best, when unharmed

by "foxey" tints of decomposed indigoand Roman

ochre, two vicious colours much used in Girtin's

time.

In his most fortunate efforts there are two

quaiities that cannot be praised too highiy; the

one is weight of styie, the other is an unfaiiing

sense of structure expressed in boid draughtsman-

ship. Suppose we examine these quaiities carefuiiy,

under separate headings.

i. —Girtin drew so weli that

his hand and eye worked together as by some secret

spontaneous impuise, unerringly, and with consum-

mate ease, hrmness, huency, truthfulness, and

precision. With equal skiil and daring he wili

draw for you a ruined abbey or a vast prospect, a

noble cathedral or a busy, crowded street, a carter

with his team of horses, a coid dawn breaking over

a stretch of mooriand, a storm in the mountairs

a waterfaii, a view of oid Paris, a simpie Engiish

viiiage, or a great line of huddled old houses seen in

rapid perspective across a river. His every touch

is quick with vitality, fuii of meaning, fuli of know-

iedge; there is nothing slovenly or haphazard in

his most rapid suggestions of form by biots of coiour.

No wonder that his friends loved to watch him at

work, and delighted to taik together about the

" sword-play " of his enchanted brush. Remember

aiso how Cotman as weli as Turner, how Dewint

and R. P. Bonington, not to speak of many lesser

men, came under his sway and profited much by

fohowing his exampie. Mr. Roget does not ex-

aggerate when he says that a group of rising painters

sprang up around Girtin, and became, under his

inftuence, the school of water-colour that Hourished

in Great Britain during the hrst haif of the nine-

teenth century. And another fact of equal impor-

tance comes to mind. Leslie, in his "Memoirs

of Constable," shows that Girtin's ascendency

over young men of genius was not conhned to the

painters in water-colour. Constable himself, the great

hope of the landscapists in oils, altered the whole

course of his practice after studying about thirty of

Girtin's works that Sir George Beaumont brought to

his notice as examples of breadth and truth. Yet

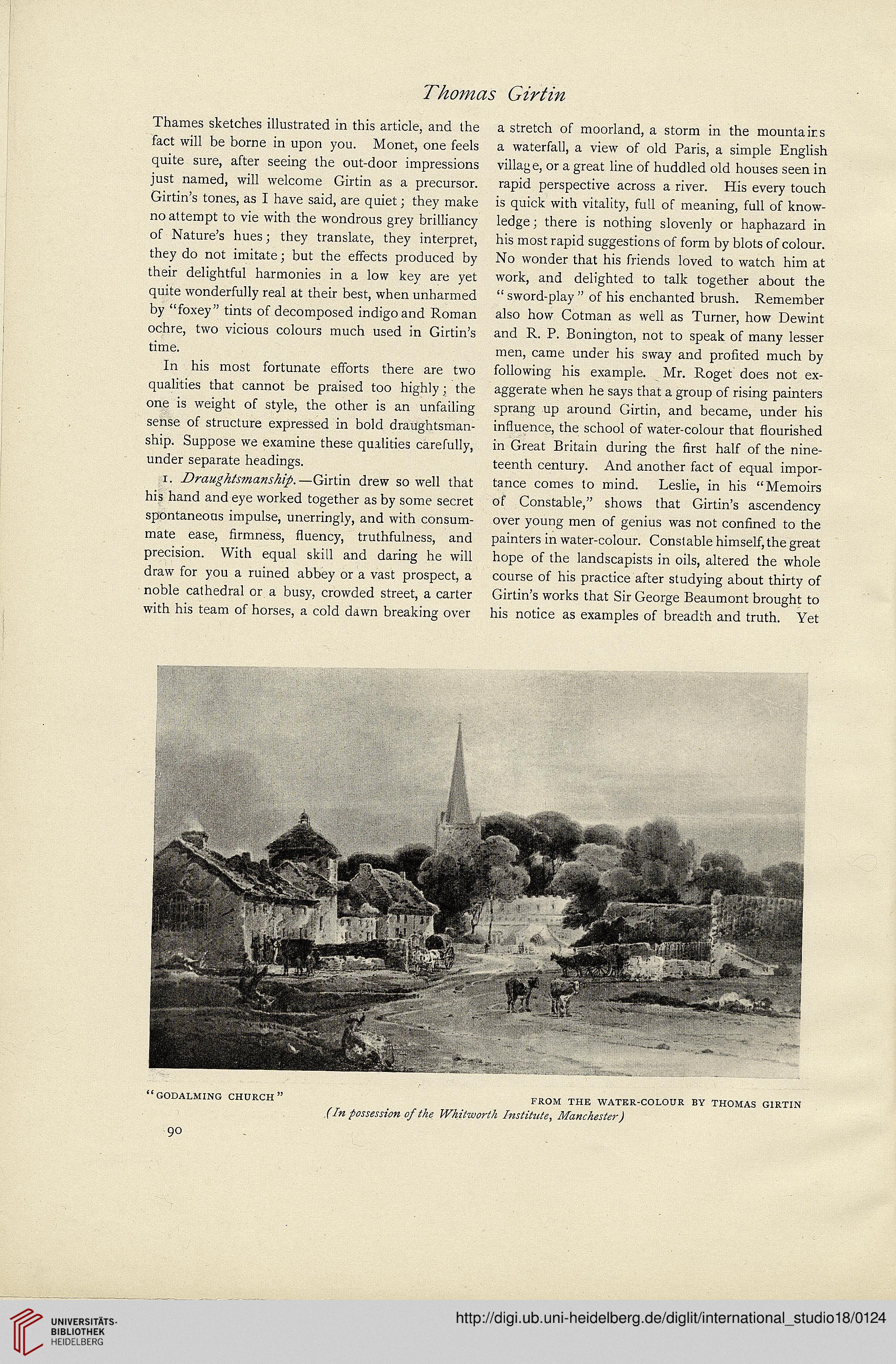

"GODALMtNG CHURCH" FROM THE WATER-COLOUR BY THOMAS GIRTtN

90

Thames sketches ittustrated in this articie, and the

fact wiii be borne in upon you. Monet, one feeis

quite sure, after seeing the out-door impressions

just named, wiii weicome Girtin as a precursor.

Girtin's tones, as I have said, are quiet; they make

no attempt to vie with the wondrous grey briiiiancy

of Nature's hues; they translate, they interpret,

theydo not imitate; but the effects produced by

their deiightfui harmonies in a iow key are yet

quite wonderfuliy real at their best, when unharmed

by "foxey" tints of decomposed indigoand Roman

ochre, two vicious colours much used in Girtin's

time.

In his most fortunate efforts there are two

quaiities that cannot be praised too highiy; the

one is weight of styie, the other is an unfaiiing

sense of structure expressed in boid draughtsman-

ship. Suppose we examine these quaiities carefuiiy,

under separate headings.

i. —Girtin drew so weli that

his hand and eye worked together as by some secret

spontaneous impuise, unerringly, and with consum-

mate ease, hrmness, huency, truthfulness, and

precision. With equal skiil and daring he wili

draw for you a ruined abbey or a vast prospect, a

noble cathedral or a busy, crowded street, a carter

with his team of horses, a coid dawn breaking over

a stretch of mooriand, a storm in the mountairs

a waterfaii, a view of oid Paris, a simpie Engiish

viiiage, or a great line of huddled old houses seen in

rapid perspective across a river. His every touch

is quick with vitality, fuii of meaning, fuli of know-

iedge; there is nothing slovenly or haphazard in

his most rapid suggestions of form by biots of coiour.

No wonder that his friends loved to watch him at

work, and delighted to taik together about the

" sword-play " of his enchanted brush. Remember

aiso how Cotman as weli as Turner, how Dewint

and R. P. Bonington, not to speak of many lesser

men, came under his sway and profited much by

fohowing his exampie. Mr. Roget does not ex-

aggerate when he says that a group of rising painters

sprang up around Girtin, and became, under his

inftuence, the school of water-colour that Hourished

in Great Britain during the hrst haif of the nine-

teenth century. And another fact of equal impor-

tance comes to mind. Leslie, in his "Memoirs

of Constable," shows that Girtin's ascendency

over young men of genius was not conhned to the

painters in water-colour. Constable himself, the great

hope of the landscapists in oils, altered the whole

course of his practice after studying about thirty of

Girtin's works that Sir George Beaumont brought to

his notice as examples of breadth and truth. Yet

"GODALMtNG CHURCH" FROM THE WATER-COLOUR BY THOMAS GIRTtN

90