98

PUNCH, OR THE LONDON CHARIVARI.

[September 7, 1878.

THE RISE AND FALL OF THE JACK SPRATTS.

A Tale of Modem Art and Fashion.

Part I.

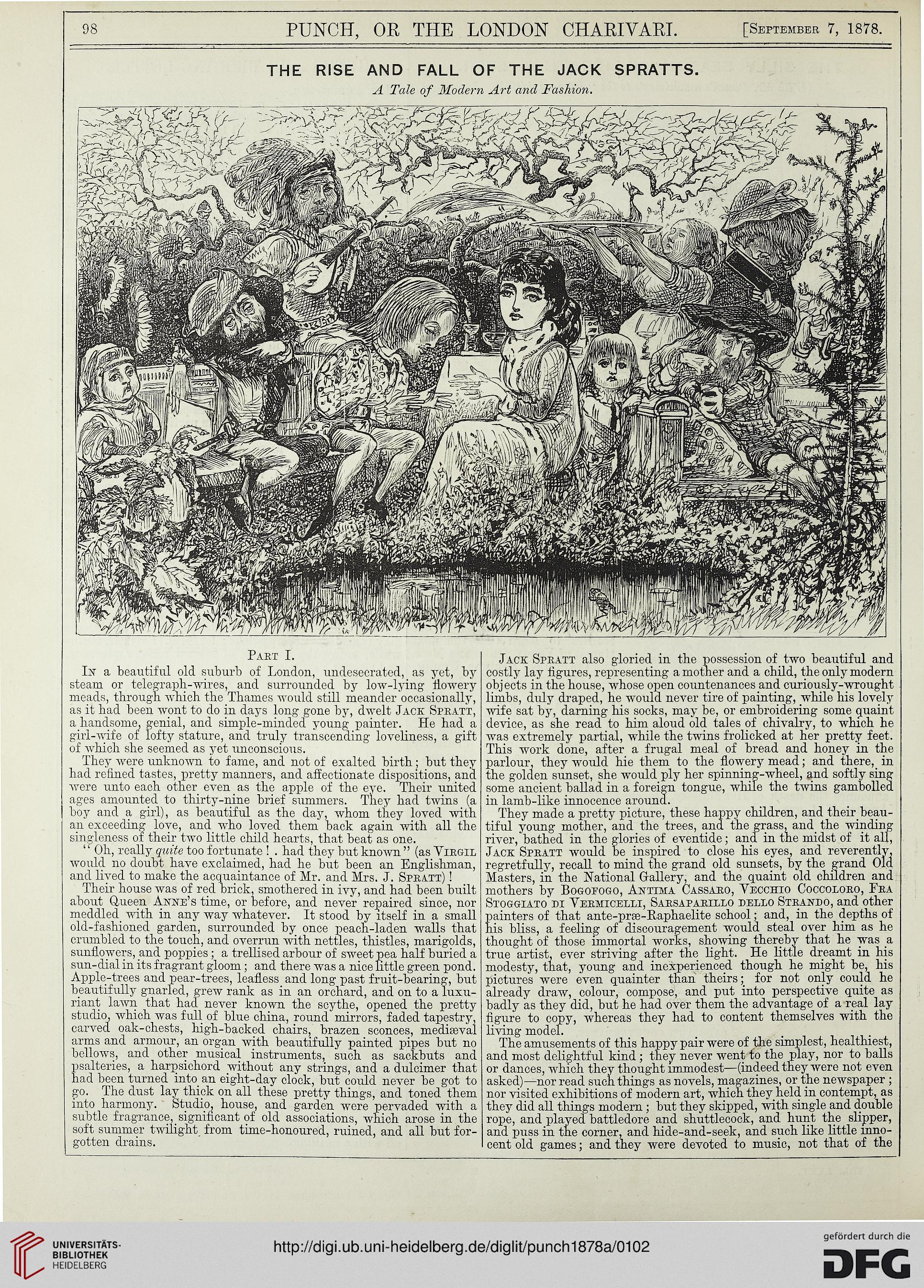

In a beautiful old suburb of London, undesecrated, as yet, by

steam or telegraph-wires, and surrounded by low-lying flowery

meads, through which the Thames would still meander occasionally,

as it had been wont to do in days long gone by, dwelt Jack Spratt,

a handsome, genial, and simple-minded young painter. He had a

girl-wife of lofty stature, and truly transcending loveliness, a gift

of which she seemed as yet unconscious.

They were unknown to fame, and not of exalted birth ; but they

had refined tastes, pretty manners, and affectionate dispositions, and

were unto each other even as the apple of the eve. Their united

ages amounted to thirty-nine brief summers. They had twins (a

boy and a girl), as beautiful as the day, whom they loved with

an exceeding love, and who loved them back again with all the

singleness of their two little child hearts, that beat as one.

' Oh, really quite too fortunate ! . had they but known " (as Virgil

would no doubt have exclaimed, had he but been an Englishman,

and lived to make the acquaintance of Mr. and Mrs. J. Spratt) !

Their house was of red brick, smothered in ivy, and had been built

about Queen Anne's time, or before, and never repaired since, nor

meddled^ with in any way whatever. It stood by itself in a small

old-fashioned garden, surrounded by once peach-laden walls that

crumbled to the touch, and overrun with nettles, thistles, marigolds,

sunflowers, and poppies ; a trellised arbour of sweet pea half buried a

sun-dial in its fragrant gloom; and there was a nice little green pond.

Apple-trees and pear-trees, leafless and long past fruit-bearing, but

beautifully gnarled, grew rank as in an orchard, and on to a luxu-

riant lawn that had never known the scythe, opened the pretty

studio, which was full of blue china, round mirrors, faded tapestry,

carved oak-chests, high-backed chairs, brazen sconces, medheval

arms and armour, an organ with beautifully painted pipes but no

bellows, and other musical instruments, such as sackbuts and

psalteries, a harpsichord without any strings, and a dulcimer that

had been turned into an eight-day clock, but could never be got to

go. The dust lay thick on all these pretty things, and toned them

into harmony. Studio, house, and garden were pervaded with a

subtle fragrance, significant of old associations, which arose in the

soft summer twilight from time-honoured, ruined, and all but for-

gotten drains.

Jack Spratt also gloried in the possession of two beautiful and

costly lay figures, representing a mother and a child, the only modern

objects in the house, whose open countenances and curiously-wrought

limbs, duly draped, he would never tire of painting, while his lovely

wife sat by, darning his socks, may be, or embroidering some quaint

device, as she read to him aloud old tales of chivalry, to which he

was extremely partial, while the twins frolicked at her pretty feet.

This work done, after a frugal meal of bread and honey in the

parlour, they would hie them to the flowery mead; and there,_ in

the golden sunset, she would ply her spinning-wheel, and softly sing

some ancient ballad in a foreign tongue, while the twins gambolled

in lamb-like innocence around.

They made a pretty picture, these happy children, and their beau-

tiful young mother, and the trees, and the grass, and the winding

river, bathed in the glories of eventide; and in the midst of it all,

Jack Spratt would be inspired to close his eyes, and reverently,

regretfully, recall to mind the grand old sunsets, by the grand Old

Masters, in the National Gallery, and the quaint old children and

mothers by Bogofogo, Antima Cassaro, Vecchio Coccoloro, Fra

Stoggiato di Vermicelli, Sarsaparillo dello Strando, and other

painters of that ante-pra3-Raphaelite school; and, in the depths of

his bliss, a feeling of discouragement would steal over him as he

thought of those immortal works, showing thereby that he was a

true artist, ever striving after the fight. He little dreamt in his

modesty, that, young and inexperienced though he might be, his

pictures were even quainter than theirs; for not only could he

already draw, colour, compose, and put into perspective quite as

badly as they did, but he had over them the advantage of a real lay

figure to copy, whereas they had to content themselves with the

living model.

The amusements of this happy pair were of the simplest, healthiest,

and most delightful kind ; they never went to the play, nor to balls

or dances, which they thought immodest—(indeed they were not even

asked)—nor read such things as novels, magazines, or the newspaper ;

nor visited exhibitions of modern art, which they held in contempt, as

they did all things modern ; but they skipped, with single and double

rope, and played battledore and shuttlecock, and hunt the slipper,

and puss in the corner, and hide-and-seek, and such like little inno-

cent old games; and they were devoted to music, not that of the

PUNCH, OR THE LONDON CHARIVARI.

[September 7, 1878.

THE RISE AND FALL OF THE JACK SPRATTS.

A Tale of Modem Art and Fashion.

Part I.

In a beautiful old suburb of London, undesecrated, as yet, by

steam or telegraph-wires, and surrounded by low-lying flowery

meads, through which the Thames would still meander occasionally,

as it had been wont to do in days long gone by, dwelt Jack Spratt,

a handsome, genial, and simple-minded young painter. He had a

girl-wife of lofty stature, and truly transcending loveliness, a gift

of which she seemed as yet unconscious.

They were unknown to fame, and not of exalted birth ; but they

had refined tastes, pretty manners, and affectionate dispositions, and

were unto each other even as the apple of the eve. Their united

ages amounted to thirty-nine brief summers. They had twins (a

boy and a girl), as beautiful as the day, whom they loved with

an exceeding love, and who loved them back again with all the

singleness of their two little child hearts, that beat as one.

' Oh, really quite too fortunate ! . had they but known " (as Virgil

would no doubt have exclaimed, had he but been an Englishman,

and lived to make the acquaintance of Mr. and Mrs. J. Spratt) !

Their house was of red brick, smothered in ivy, and had been built

about Queen Anne's time, or before, and never repaired since, nor

meddled^ with in any way whatever. It stood by itself in a small

old-fashioned garden, surrounded by once peach-laden walls that

crumbled to the touch, and overrun with nettles, thistles, marigolds,

sunflowers, and poppies ; a trellised arbour of sweet pea half buried a

sun-dial in its fragrant gloom; and there was a nice little green pond.

Apple-trees and pear-trees, leafless and long past fruit-bearing, but

beautifully gnarled, grew rank as in an orchard, and on to a luxu-

riant lawn that had never known the scythe, opened the pretty

studio, which was full of blue china, round mirrors, faded tapestry,

carved oak-chests, high-backed chairs, brazen sconces, medheval

arms and armour, an organ with beautifully painted pipes but no

bellows, and other musical instruments, such as sackbuts and

psalteries, a harpsichord without any strings, and a dulcimer that

had been turned into an eight-day clock, but could never be got to

go. The dust lay thick on all these pretty things, and toned them

into harmony. Studio, house, and garden were pervaded with a

subtle fragrance, significant of old associations, which arose in the

soft summer twilight from time-honoured, ruined, and all but for-

gotten drains.

Jack Spratt also gloried in the possession of two beautiful and

costly lay figures, representing a mother and a child, the only modern

objects in the house, whose open countenances and curiously-wrought

limbs, duly draped, he would never tire of painting, while his lovely

wife sat by, darning his socks, may be, or embroidering some quaint

device, as she read to him aloud old tales of chivalry, to which he

was extremely partial, while the twins frolicked at her pretty feet.

This work done, after a frugal meal of bread and honey in the

parlour, they would hie them to the flowery mead; and there,_ in

the golden sunset, she would ply her spinning-wheel, and softly sing

some ancient ballad in a foreign tongue, while the twins gambolled

in lamb-like innocence around.

They made a pretty picture, these happy children, and their beau-

tiful young mother, and the trees, and the grass, and the winding

river, bathed in the glories of eventide; and in the midst of it all,

Jack Spratt would be inspired to close his eyes, and reverently,

regretfully, recall to mind the grand old sunsets, by the grand Old

Masters, in the National Gallery, and the quaint old children and

mothers by Bogofogo, Antima Cassaro, Vecchio Coccoloro, Fra

Stoggiato di Vermicelli, Sarsaparillo dello Strando, and other

painters of that ante-pra3-Raphaelite school; and, in the depths of

his bliss, a feeling of discouragement would steal over him as he

thought of those immortal works, showing thereby that he was a

true artist, ever striving after the fight. He little dreamt in his

modesty, that, young and inexperienced though he might be, his

pictures were even quainter than theirs; for not only could he

already draw, colour, compose, and put into perspective quite as

badly as they did, but he had over them the advantage of a real lay

figure to copy, whereas they had to content themselves with the

living model.

The amusements of this happy pair were of the simplest, healthiest,

and most delightful kind ; they never went to the play, nor to balls

or dances, which they thought immodest—(indeed they were not even

asked)—nor read such things as novels, magazines, or the newspaper ;

nor visited exhibitions of modern art, which they held in contempt, as

they did all things modern ; but they skipped, with single and double

rope, and played battledore and shuttlecock, and hunt the slipper,

and puss in the corner, and hide-and-seek, and such like little inno-

cent old games; and they were devoted to music, not that of the