Goya

that accepts the doctrines of anarchy, while

agnostics look upon him with pride as the man

who helped to kill the Inquisition with a graver’s

needle. Whether the enthusiastic partisans of

many cults are justified of their enthusiasms I do

not pretend to know, but the truth remains that

Goya’s work has certain qualities that appeal

to men of all shades of thought and tempera-

ment who have nothing in common except an

intelligent interest in the phenomena of life.

The pictures here reproduced are a striking

comment upon the artist’s versatility, upon his

strange power of presenting abstractions

through the medium of pictures, and

conveying an impression so powerful that

the ordinary gifts and graces we look for

from artists of a smaller power are never

missed. Goya, the Spanish apostle of Revo-

lution, turned deliberately from the schools

and the contemporary convention of art:

he looked straight before him, and set down

life as he saw it. Unlike many great painters,

his range of vision was unlimited and was

impersonal. Some men, whose work has

made a profound impression upon their

generation, whose paintings are better known

and more highly esteemed than Goya’s, have

limitations so curious and marked that the

student knows their canvases at sight—the

thoughts that inspired the picture, the

handling that gave it birth. The names of

Jean Frangois Millet, Puvis de Chavannes,

and Burne-Jones appear to me in this con-

nection as I write. They painted life not

as it is, but as they dreamed of it; vision-

aries all, they strove beautifully in their

working hours, and our gratitude is' their

imperishable reward. Goya, on the other

hand, had moods in which the gift of clear

vision lighted upon him as strength came

to Samson in the vineyards of Timnah. In

one mood the charm of childhood im-

presses itself upon him; he paints the por-

trait of his grandson, which now belongs to

the Marquis of Alcanices and is reproduced

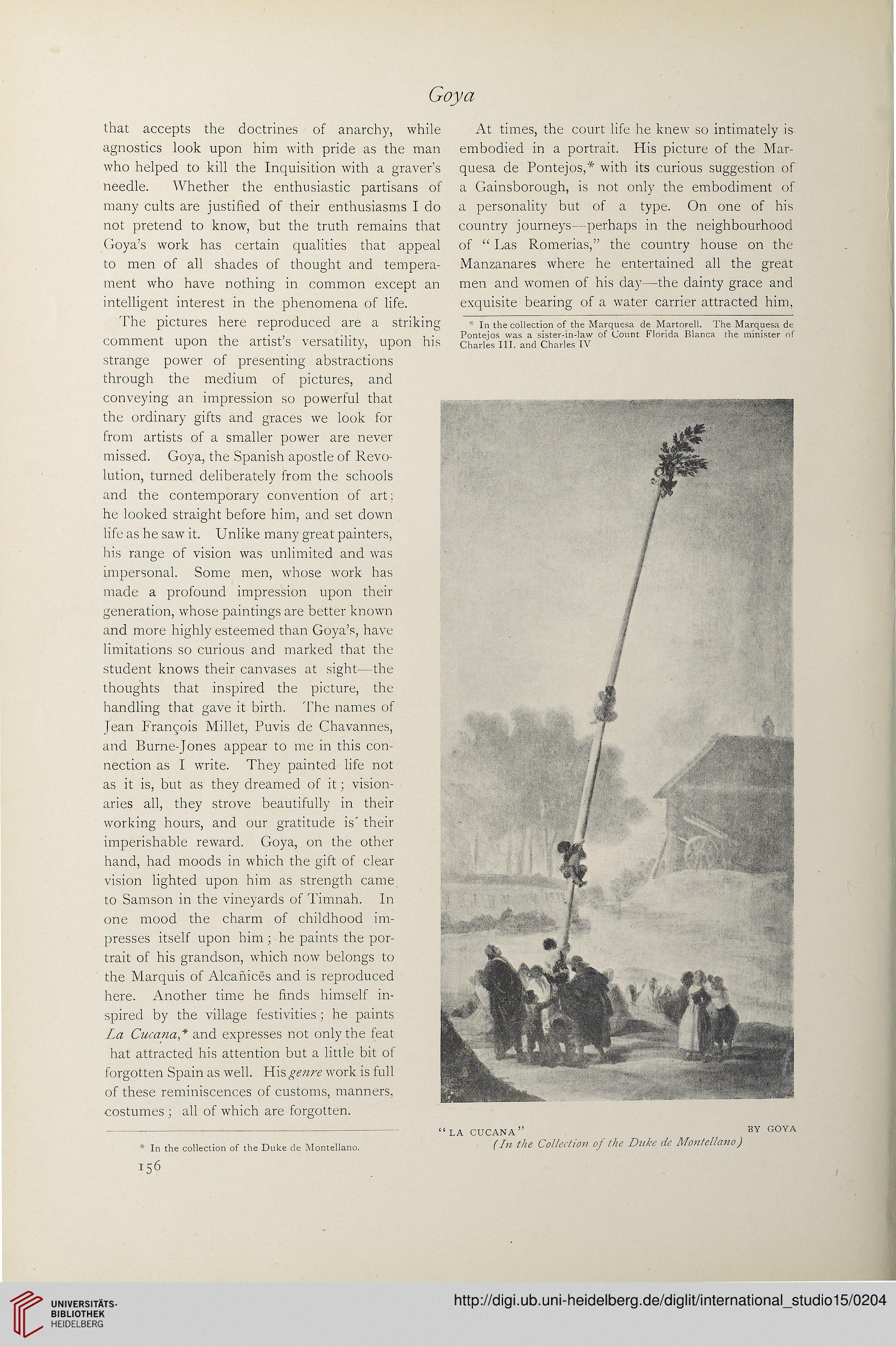

here. Another time he finds himself in-

spired by the village festivities; he paints

La Cucanaf and expresses not only the feat

hat attracted his attention but a little bit of

forgotten Spain as well. genre work is full

of these reminiscences of customs, manners,

costumes ; all of which are forgotten.

* In the collection of the Duke de Montellano.

J56

At times, the court life he knew so intimately is

embodied in a portrait. His picture of the Mar-

quesa de Pontejos,* with its curious suggestion of

a Gainsborough, is not only the embodiment of

a personality but of a type. On one of his

country journeys—perhaps in the neighbourhood

of “ Las Romerias,” the country house on the

Manzanares where he entertained all the great

men and women of his day—the dainty grace and

exquisite bearing of a water carrier attracted him,

* In the collection of the Marquesa de Martorell. The Marquesa de

Pontejos was a sister-in-law of Count Florida Blanca the minister of

Charles III. and Charles IV

“LA CUCANA” BY GOYA

(In the Collection of the Duke de Montellano)

that accepts the doctrines of anarchy, while

agnostics look upon him with pride as the man

who helped to kill the Inquisition with a graver’s

needle. Whether the enthusiastic partisans of

many cults are justified of their enthusiasms I do

not pretend to know, but the truth remains that

Goya’s work has certain qualities that appeal

to men of all shades of thought and tempera-

ment who have nothing in common except an

intelligent interest in the phenomena of life.

The pictures here reproduced are a striking

comment upon the artist’s versatility, upon his

strange power of presenting abstractions

through the medium of pictures, and

conveying an impression so powerful that

the ordinary gifts and graces we look for

from artists of a smaller power are never

missed. Goya, the Spanish apostle of Revo-

lution, turned deliberately from the schools

and the contemporary convention of art:

he looked straight before him, and set down

life as he saw it. Unlike many great painters,

his range of vision was unlimited and was

impersonal. Some men, whose work has

made a profound impression upon their

generation, whose paintings are better known

and more highly esteemed than Goya’s, have

limitations so curious and marked that the

student knows their canvases at sight—the

thoughts that inspired the picture, the

handling that gave it birth. The names of

Jean Frangois Millet, Puvis de Chavannes,

and Burne-Jones appear to me in this con-

nection as I write. They painted life not

as it is, but as they dreamed of it; vision-

aries all, they strove beautifully in their

working hours, and our gratitude is' their

imperishable reward. Goya, on the other

hand, had moods in which the gift of clear

vision lighted upon him as strength came

to Samson in the vineyards of Timnah. In

one mood the charm of childhood im-

presses itself upon him; he paints the por-

trait of his grandson, which now belongs to

the Marquis of Alcanices and is reproduced

here. Another time he finds himself in-

spired by the village festivities; he paints

La Cucanaf and expresses not only the feat

hat attracted his attention but a little bit of

forgotten Spain as well. genre work is full

of these reminiscences of customs, manners,

costumes ; all of which are forgotten.

* In the collection of the Duke de Montellano.

J56

At times, the court life he knew so intimately is

embodied in a portrait. His picture of the Mar-

quesa de Pontejos,* with its curious suggestion of

a Gainsborough, is not only the embodiment of

a personality but of a type. On one of his

country journeys—perhaps in the neighbourhood

of “ Las Romerias,” the country house on the

Manzanares where he entertained all the great

men and women of his day—the dainty grace and

exquisite bearing of a water carrier attracted him,

* In the collection of the Marquesa de Martorell. The Marquesa de

Pontejos was a sister-in-law of Count Florida Blanca the minister of

Charles III. and Charles IV

“LA CUCANA” BY GOYA

(In the Collection of the Duke de Montellano)