The New English Art Club

fr

K«v.

x ) o .&a/.

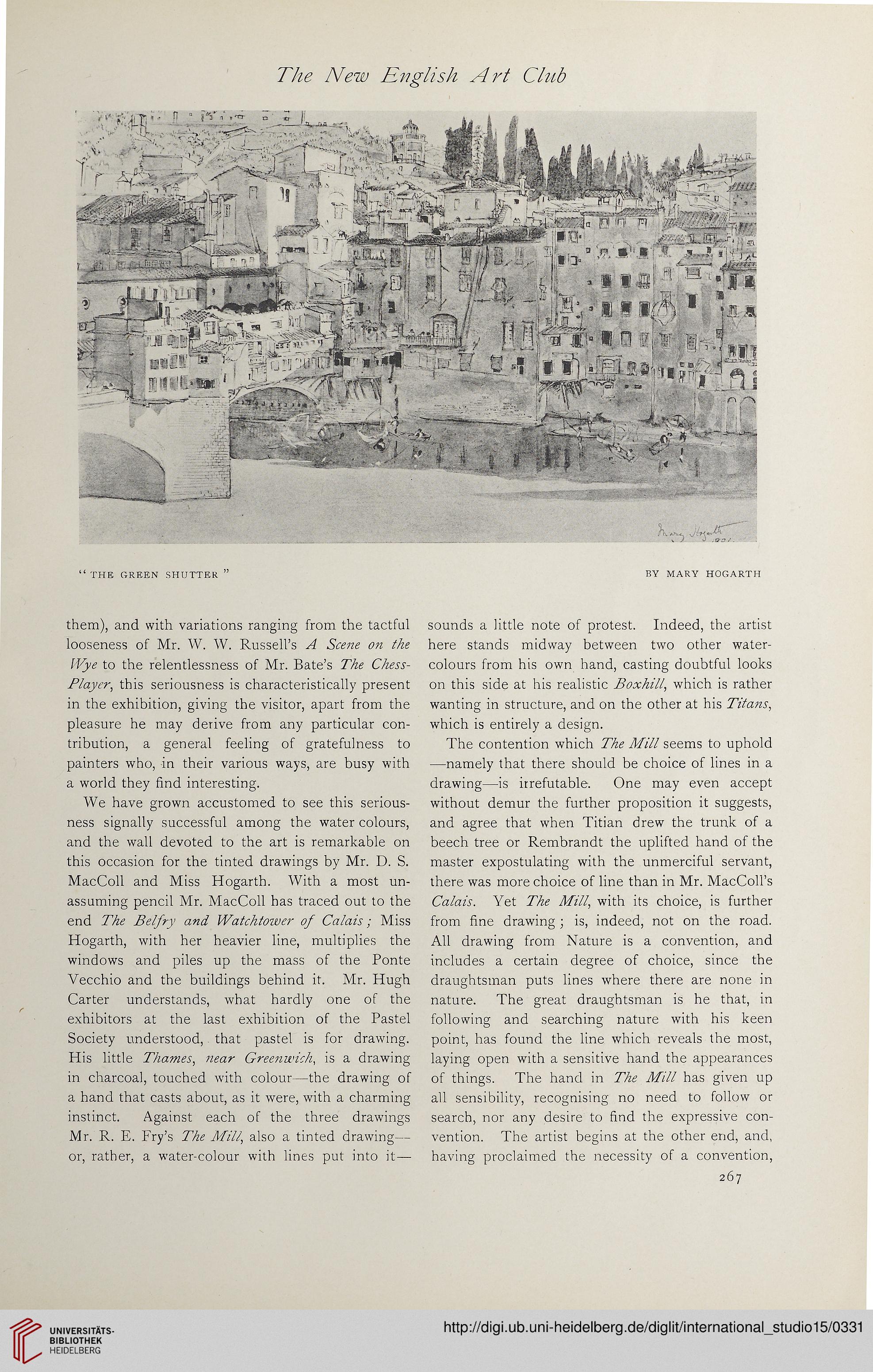

“ THE GREEN SHUTTER

BY MARY HOGARTH

them), and with variations ranging from the tactful

looseness of Mr. W. W. Russell’s A Scene on the

Wye to the relentlessness of Mr. Bate’s The Chess-

Player, this seriousness is characteristically present

in the exhibition, giving the visitor, apart from the

pleasure he may derive from any particular con-

tribution, a general feeling of gratefulness to

painters who, in their various ways, are busy with

a world they find interesting.

We have grown accustomed to see this serious-

ness signally successful among the water colours,

and the wall devoted to the art is remarkable on

this occasion for the tinted drawings by Mr. D. S.

MacColl and Miss Hogarth. With a most un-

assuming pencil Mr. MacColl has traced out to the

end The Belfry and Watchtower of Calais; Miss

Hogarth, with her heavier line, multiplies the

windows and piles up the mass of the Ponte

Vecchio and the buildings behind it. Mr. Hugh

Carter understands, what hardly one of the

exhibitors at the last exhibition of the Pastel

Society understood, that pastel is for drawing.

His little Thames, near Greenwich, is a drawing

in charcoal, touched with colour—the drawing of

a hand that casts about, as it were, with a charming

instinct. Against each of the three drawings

Mr. R. E. Fry’s The Mill, also a tinted drawing—

or, rather, a water-colour with lines put into it —

sounds a little note of protest. Indeed, the artist

here stands midway between two other water-

colours from his own hand, casting doubtful looks

on this side at his realistic Boxhill, which is rather

wanting in structure, and on the other at his Titans,

which is entirely a design.

The contention which The Mill seems to uphold

—namely that there should be choice of lines in a

drawing—is irrefutable. One may even accept

without demur the further proposition it suggests,

and agree that when Titian drew the trunk of a

beech tree or Rembrandt the uplifted hand of the

master expostulating with the unmerciful servant,

there was more choice of line than in Mr. MacColl’s

Calais. Yet The Mill, with its choice, is further

from fine drawing; is, indeed, not on the road.

All drawing from Nature is a convention, and

includes a certain degree of choice, since the

draughtsman puts lines where there are none in

nature. The great draughtsman is he that, in

following and searching nature with his keen

point, has found the line which reveals the most,

laying open with a sensitive hand the appearances

of things. The hand in The Mill has given up

all sensibility, recognising no need to follow or

search, nor any desire to find the expressive con-

vention. The artist begins at the other end, and,

having proclaimed the necessity of a convention,

267

fr

K«v.

x ) o .&a/.

“ THE GREEN SHUTTER

BY MARY HOGARTH

them), and with variations ranging from the tactful

looseness of Mr. W. W. Russell’s A Scene on the

Wye to the relentlessness of Mr. Bate’s The Chess-

Player, this seriousness is characteristically present

in the exhibition, giving the visitor, apart from the

pleasure he may derive from any particular con-

tribution, a general feeling of gratefulness to

painters who, in their various ways, are busy with

a world they find interesting.

We have grown accustomed to see this serious-

ness signally successful among the water colours,

and the wall devoted to the art is remarkable on

this occasion for the tinted drawings by Mr. D. S.

MacColl and Miss Hogarth. With a most un-

assuming pencil Mr. MacColl has traced out to the

end The Belfry and Watchtower of Calais; Miss

Hogarth, with her heavier line, multiplies the

windows and piles up the mass of the Ponte

Vecchio and the buildings behind it. Mr. Hugh

Carter understands, what hardly one of the

exhibitors at the last exhibition of the Pastel

Society understood, that pastel is for drawing.

His little Thames, near Greenwich, is a drawing

in charcoal, touched with colour—the drawing of

a hand that casts about, as it were, with a charming

instinct. Against each of the three drawings

Mr. R. E. Fry’s The Mill, also a tinted drawing—

or, rather, a water-colour with lines put into it —

sounds a little note of protest. Indeed, the artist

here stands midway between two other water-

colours from his own hand, casting doubtful looks

on this side at his realistic Boxhill, which is rather

wanting in structure, and on the other at his Titans,

which is entirely a design.

The contention which The Mill seems to uphold

—namely that there should be choice of lines in a

drawing—is irrefutable. One may even accept

without demur the further proposition it suggests,

and agree that when Titian drew the trunk of a

beech tree or Rembrandt the uplifted hand of the

master expostulating with the unmerciful servant,

there was more choice of line than in Mr. MacColl’s

Calais. Yet The Mill, with its choice, is further

from fine drawing; is, indeed, not on the road.

All drawing from Nature is a convention, and

includes a certain degree of choice, since the

draughtsman puts lines where there are none in

nature. The great draughtsman is he that, in

following and searching nature with his keen

point, has found the line which reveals the most,

laying open with a sensitive hand the appearances

of things. The hand in The Mill has given up

all sensibility, recognising no need to follow or

search, nor any desire to find the expressive con-

vention. The artist begins at the other end, and,

having proclaimed the necessity of a convention,

267