The Darmstadt Artists Colony

of furniture, the response is a sigh. “ There

is no simple modern furniture,” he declares.

“ It is either beyond one’s means or doesn’t

fit into the home and the life of ordinary man.”

Those who thus relieve their feelings by sighs,

not always without cause, will, to judge by his

work in the Darmstadt Colony, find in Patriz

Huber a ready helper, and will derive from his

interiors the conviction that simple middle-class

furniture may be produced which will meet modern

art requirements. Middle-class — burgerlich — the

word is very expressive of a certain kind of interior

architecture. And if we seek for another signifi-

cant word, “ German ” soon suggests itself.

“ Middle class ” and “German”—this is indeed

the tendency in all the rooms of Habich’s house,

of Gliickert’s house, and in the bachelors’ dwellings

which have been designed by Huber in the Colony.

Now, the word “ German ”—in using which we have

to take in all shades of Germanism from the utmost

north to the extreme south, including Munich art,

for instance, but excluding that of the Viennese—

naturally comprises a great range of peculiarities,

of typical values. Essentially “ German ” is

Heinrich Vogeler, the painter and etcher of

Worpswede, who often designs furniture, in his

graceful yet angular manner. “ German,” too, was

the entire “ Biedermaier ” style. “ German,” too,

the fashion of richly - carved furniture; and

“ German ” the desire to live as the French and

Italians of former centuries lived. But when I

apply the epithets “ German ” and “middle-class ”

to Huber’s interiors much is expressed. In the

first place the artist is conscious of the fact that

he is raising dwellings and designing furniture

for ordinary men. He begins by excluding

extravagance in colour and outline. His aim is

comfort combined with agreeable effect. Of course

he is also endeavouring to found a new style.

Only he seeks his effects less by designing rooms

strongly individual—individual, that is, as regards

the inmates—than by inventing new forms for typical

furniture. Any number of people could live in

Gluckert’s house; even Habich’s house, which has

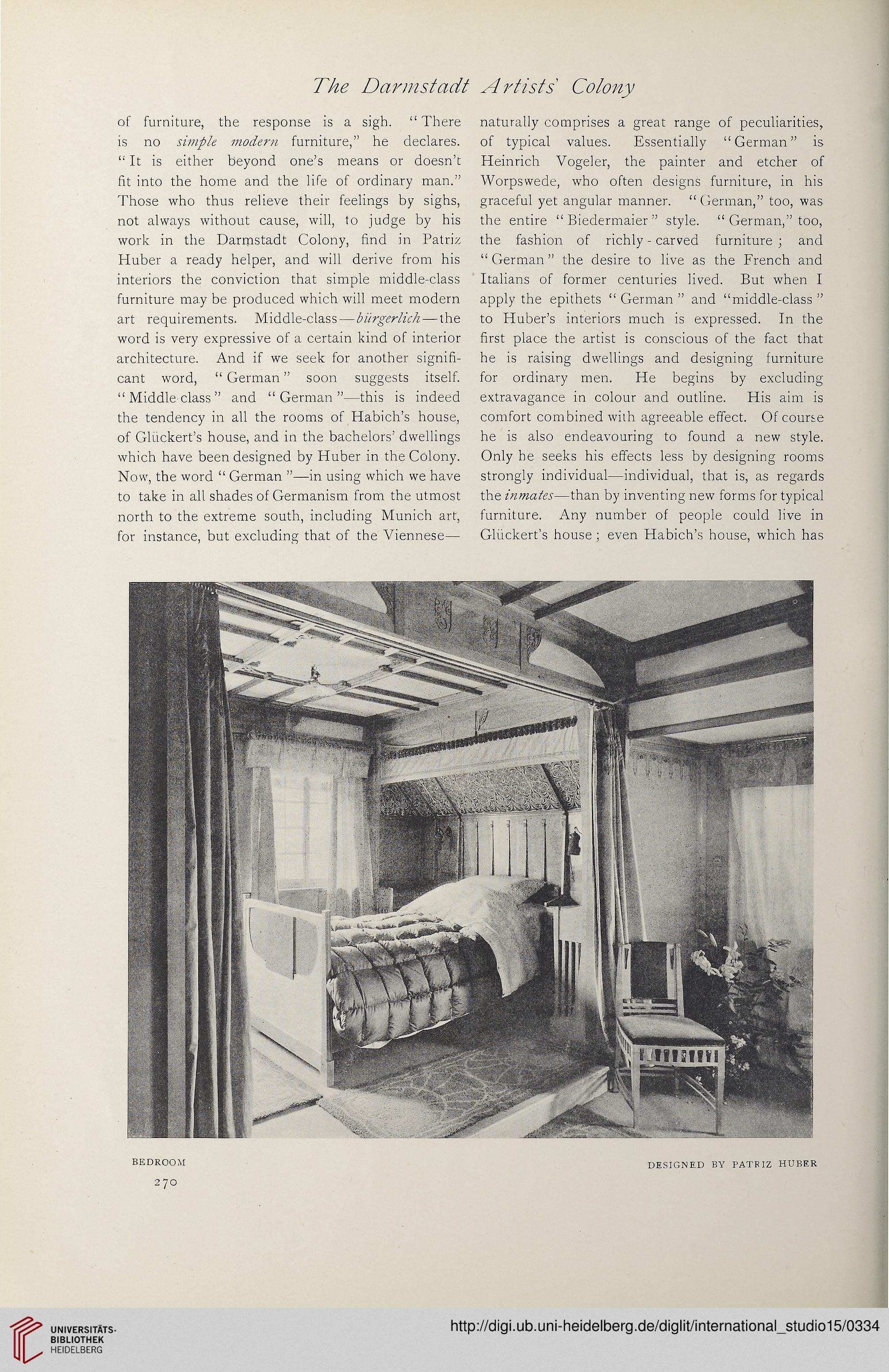

BEDROOM

270

DESIGNED BY PATEIZ HUBER

of furniture, the response is a sigh. “ There

is no simple modern furniture,” he declares.

“ It is either beyond one’s means or doesn’t

fit into the home and the life of ordinary man.”

Those who thus relieve their feelings by sighs,

not always without cause, will, to judge by his

work in the Darmstadt Colony, find in Patriz

Huber a ready helper, and will derive from his

interiors the conviction that simple middle-class

furniture may be produced which will meet modern

art requirements. Middle-class — burgerlich — the

word is very expressive of a certain kind of interior

architecture. And if we seek for another signifi-

cant word, “ German ” soon suggests itself.

“ Middle class ” and “German”—this is indeed

the tendency in all the rooms of Habich’s house,

of Gliickert’s house, and in the bachelors’ dwellings

which have been designed by Huber in the Colony.

Now, the word “ German ”—in using which we have

to take in all shades of Germanism from the utmost

north to the extreme south, including Munich art,

for instance, but excluding that of the Viennese—

naturally comprises a great range of peculiarities,

of typical values. Essentially “ German ” is

Heinrich Vogeler, the painter and etcher of

Worpswede, who often designs furniture, in his

graceful yet angular manner. “ German,” too, was

the entire “ Biedermaier ” style. “ German,” too,

the fashion of richly - carved furniture; and

“ German ” the desire to live as the French and

Italians of former centuries lived. But when I

apply the epithets “ German ” and “middle-class ”

to Huber’s interiors much is expressed. In the

first place the artist is conscious of the fact that

he is raising dwellings and designing furniture

for ordinary men. He begins by excluding

extravagance in colour and outline. His aim is

comfort combined with agreeable effect. Of course

he is also endeavouring to found a new style.

Only he seeks his effects less by designing rooms

strongly individual—individual, that is, as regards

the inmates—than by inventing new forms for typical

furniture. Any number of people could live in

Gluckert’s house; even Habich’s house, which has

BEDROOM

270

DESIGNED BY PATEIZ HUBER