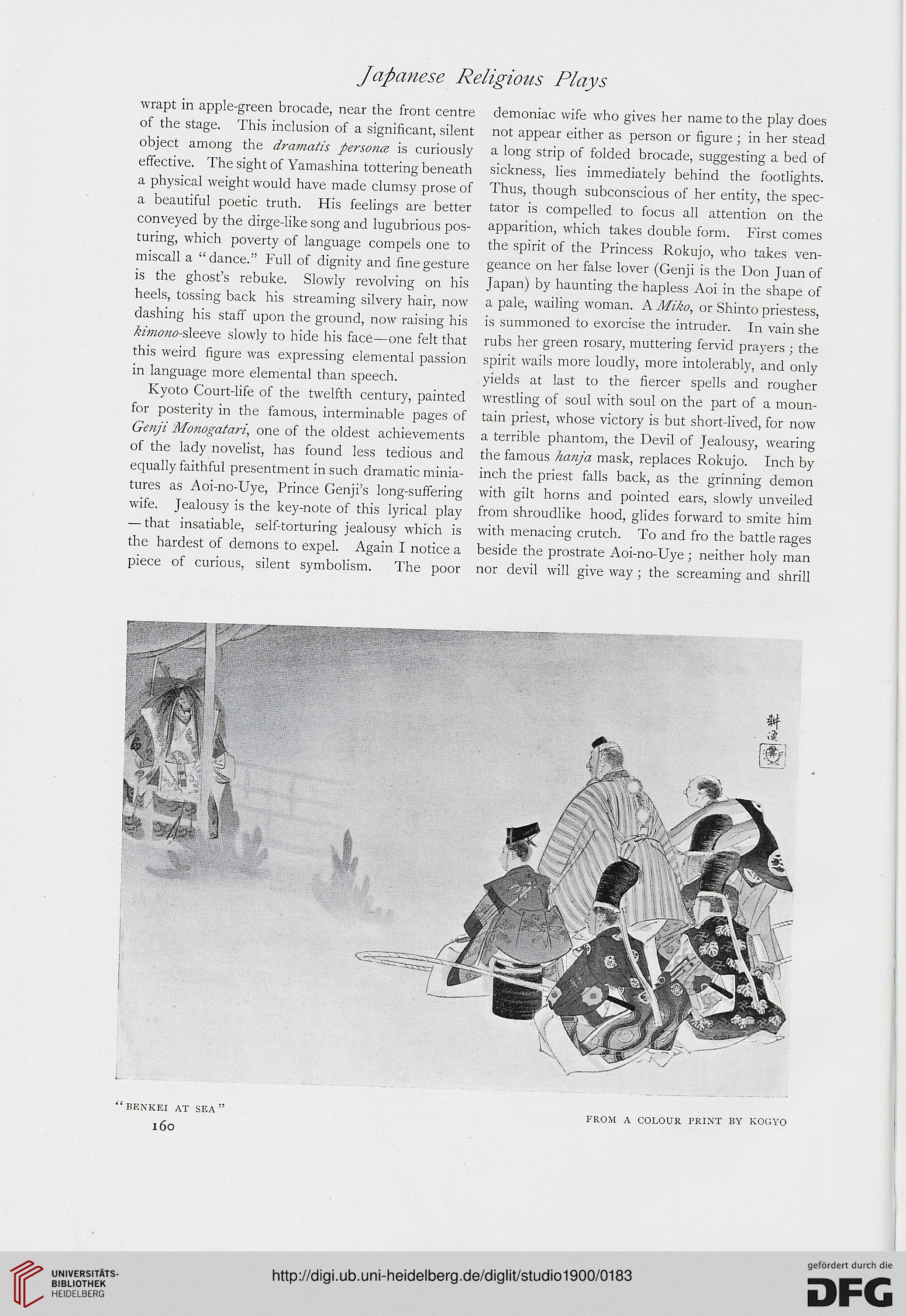

Japanese Religions Plays

wrapt in apple-green brocade, near the front centre

of the stage. This inclusion of a significant, silent

object among the dramatis persona; is curiously

effective. The sight of Yamashina tottering beneath

a physical weight would have made clumsy prose of

a beautiful poetic truth. His feelings are better

conveyed by the dirge-like song and lugubrious pos-

turing, which poverty of language compels one to

miscall a " dance." Full of dignity and fine gesture

is the ghost's rebuke. Slowly revolving on his

heels, tossing back his streaming silvery hair, now

dashing his staff upon the ground, now raising his

Aimcmo-sleeve slowly to hide his face—one felt that

this weird figure was expressing elemental passion

in language more elemental than speech.

Kyoto Court-life of the twelfth century, painted

for posterity in the famous, interminable pages of

Genji Monogatari, one of the oldest achievements

of the lady novelist, has found less tedious and

equally faithful presentment in such dramatic minia-

tures as Aoi-no-Uye, Prince Genji's long-suffering

wife. Jealousy is the key-note of this lyrical play

— that insatiable, self-torturing jealousy which is

the hardest of demons to expel. Again I notice a

piece of curious, silent symbolism. The poor

demoniac wife who gives her name to the play does

not appear either as person or figure ; in her stead

a long strip of folded brocade, suggesting a bed of

sickness, lies immediately behind the footlights.

Thus, though subconscious of her entity, the spec-

tator is compelled to focus all attention on the

apparition, which takes double form. First comes

the spirit of the Princess Rokujo, who takes ven-

geance on her false lover (Genji is the Don Juan of

Japan) by haunting the hapless Aoi in the shape of

a pale, wailing woman. KMiko, or Shinto priestess,

is summoned to exorcise the intruder. In vain she

rubs her green rosary, muttering fervid prayers • the

spirit wails more loudly, more intolerably, and only

yields at last to the fiercer spells and rougher

wrestling of soul with soul on the part of a moun-

tain priest, whose victory is but short-lived, for now

a terrible phantom, the Devil of Jealousy, wearing

the famous hanja mask, replaces Rokujo. Inch by

inch the priest falls back, as the grinning demon

with gilt horns and pointed ears, slowly unveiled

from shroudlike hood, glides forward to smite him

with menacing crutch. To and fro the battle rages

beside the prostrate Aoi-no-Uye; neither holy man

nor devil will give way ; the screaming and shrill

wrapt in apple-green brocade, near the front centre

of the stage. This inclusion of a significant, silent

object among the dramatis persona; is curiously

effective. The sight of Yamashina tottering beneath

a physical weight would have made clumsy prose of

a beautiful poetic truth. His feelings are better

conveyed by the dirge-like song and lugubrious pos-

turing, which poverty of language compels one to

miscall a " dance." Full of dignity and fine gesture

is the ghost's rebuke. Slowly revolving on his

heels, tossing back his streaming silvery hair, now

dashing his staff upon the ground, now raising his

Aimcmo-sleeve slowly to hide his face—one felt that

this weird figure was expressing elemental passion

in language more elemental than speech.

Kyoto Court-life of the twelfth century, painted

for posterity in the famous, interminable pages of

Genji Monogatari, one of the oldest achievements

of the lady novelist, has found less tedious and

equally faithful presentment in such dramatic minia-

tures as Aoi-no-Uye, Prince Genji's long-suffering

wife. Jealousy is the key-note of this lyrical play

— that insatiable, self-torturing jealousy which is

the hardest of demons to expel. Again I notice a

piece of curious, silent symbolism. The poor

demoniac wife who gives her name to the play does

not appear either as person or figure ; in her stead

a long strip of folded brocade, suggesting a bed of

sickness, lies immediately behind the footlights.

Thus, though subconscious of her entity, the spec-

tator is compelled to focus all attention on the

apparition, which takes double form. First comes

the spirit of the Princess Rokujo, who takes ven-

geance on her false lover (Genji is the Don Juan of

Japan) by haunting the hapless Aoi in the shape of

a pale, wailing woman. KMiko, or Shinto priestess,

is summoned to exorcise the intruder. In vain she

rubs her green rosary, muttering fervid prayers • the

spirit wails more loudly, more intolerably, and only

yields at last to the fiercer spells and rougher

wrestling of soul with soul on the part of a moun-

tain priest, whose victory is but short-lived, for now

a terrible phantom, the Devil of Jealousy, wearing

the famous hanja mask, replaces Rokujo. Inch by

inch the priest falls back, as the grinning demon

with gilt horns and pointed ears, slowly unveiled

from shroudlike hood, glides forward to smite him

with menacing crutch. To and fro the battle rages

beside the prostrate Aoi-no-Uye; neither holy man

nor devil will give way ; the screaming and shrill