Maori IVood Carving

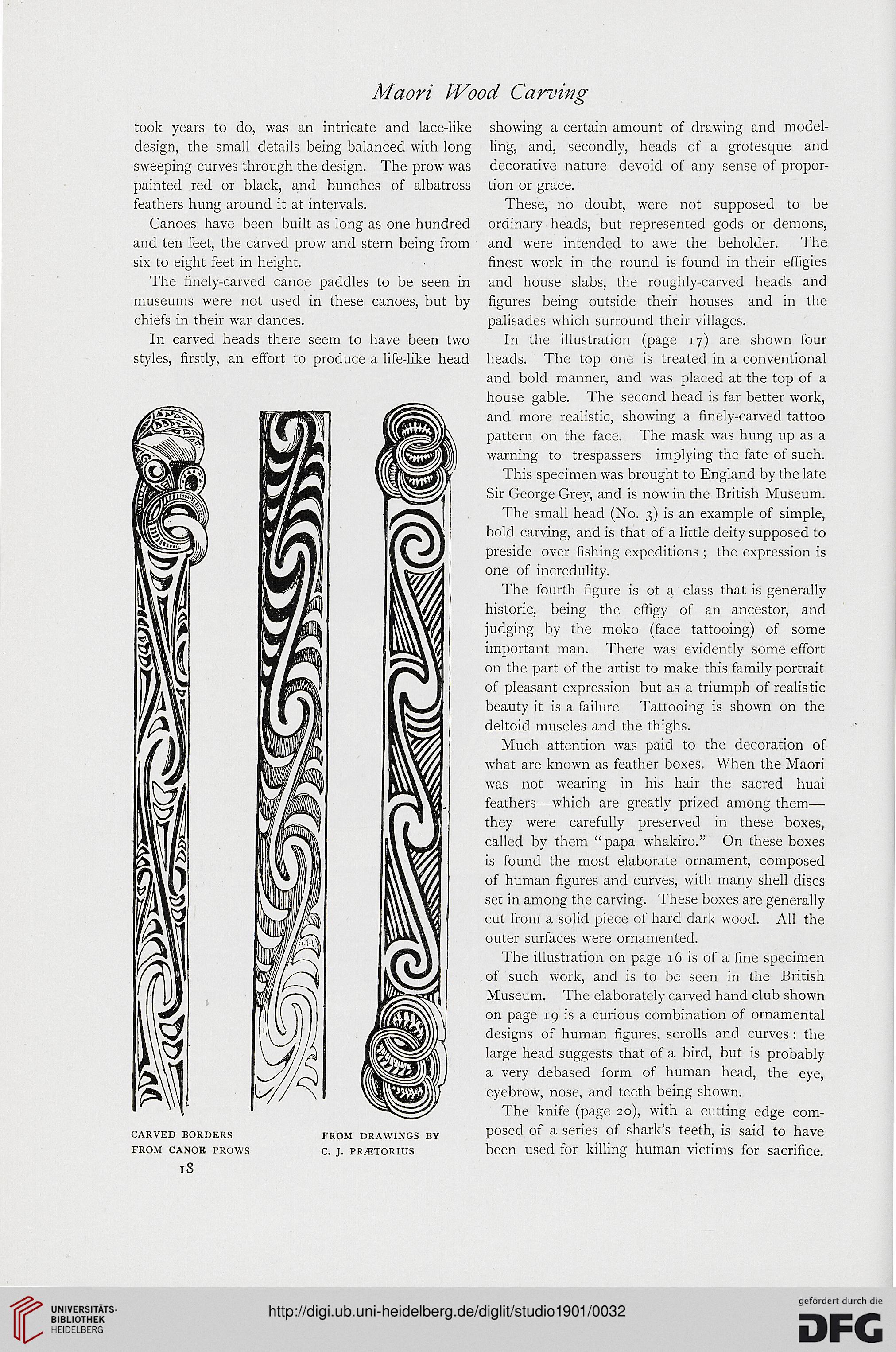

took years to do, was an intricate and lace-like

design, the small details being balanced with long

sweeping curves through the design. The prow was

painted red or black, and bunches of albatross

feathers hung around it at intervals.

Canoes have been built as long as one hundred

and ten feet, the carved prow and stern being from

six to eight feet in height.

The finely-carved canoe paddles to be seen in

museums were not used in these canoes, but by

chiefs in their war dances.

In carved heads there seem to have been two

styles, firstly, an effort to produce a life-like head

CARVED BORDERS FROM DRAWINGS BY

FROM CANOE PRuWS C. J. PR/F.TORIUS

tS

showing a certain amount of drawing and model-

ling, and, secondly, heads of a grotesque and

decorative nature devoid of any sense of propor-

tion or grace.

These, no doubt, were not supposed to be

ordinary heads, but represented gods or demons,

and were intended to awe the beholder. The

finest work in the round is found in their effigies

and house slabs, the roughly-carved heads and

figures being outside their houses and in the

palisades which surround their villages.

In the illustration (page 17) are shown four

heads. The top one is treated in a conventional

and bold manner, and was placed at the top of a

house gable. The second head is far better work,

and more realistic, showing a finely-carved tattoo

pattern on the face. The mask was hung up as a

warning to trespassers implying the fate of such.

This specimen was brought to England by the late

Sir George Grey, and is now in the British Museum.

The small head (No. 3) is an example of simple,

bold carving, and is that of a little deity supposed to

preside over fishing expeditions ; the expression is

one of incredulity.

The fourth figure is ot a class that is generally

historic, being the effigy of an ancestor, and

judging by the moko (face tattooing) of some

important man. There was evidently some effort

on the part of the artist to make this family portrait

of pleasant expression but as a triumph of realistic

beauty it is a failure Tattooing is shown on the

deltoid muscles and the thighs.

Much attention was paid to the decoration of

what are known as feather boxes. When the Maori

was not wearing in his hair the sacred huai

feathers—which are greatly prized among them—

they were carefully preserved in these boxes,

called by them "papa whakiro." On these boxes

is found the most elaborate ornament, composed

of human figures and curves, with many shell discs

set in among the carving. These boxes are generally

cut from a solid piece of hard dark wood. All the

outer surfaces were ornamented.

The illustration on page 16 is of a fine specimen

of such work, and is to be seen in the British

Museum. The elaborately carved hand club shown

on page 19 is a curious combination of ornamental

designs of human figures, scrolls and curves : the

large head suggests that of a bird, but is probably

a very debased form of human head, the eye,

eyebrow, nose, and teeth being shown.

The knife (page 20), with a cutting edge com-

posed of a series of shark's teeth, is said to have

been used for killing human victims for sacrifice.

took years to do, was an intricate and lace-like

design, the small details being balanced with long

sweeping curves through the design. The prow was

painted red or black, and bunches of albatross

feathers hung around it at intervals.

Canoes have been built as long as one hundred

and ten feet, the carved prow and stern being from

six to eight feet in height.

The finely-carved canoe paddles to be seen in

museums were not used in these canoes, but by

chiefs in their war dances.

In carved heads there seem to have been two

styles, firstly, an effort to produce a life-like head

CARVED BORDERS FROM DRAWINGS BY

FROM CANOE PRuWS C. J. PR/F.TORIUS

tS

showing a certain amount of drawing and model-

ling, and, secondly, heads of a grotesque and

decorative nature devoid of any sense of propor-

tion or grace.

These, no doubt, were not supposed to be

ordinary heads, but represented gods or demons,

and were intended to awe the beholder. The

finest work in the round is found in their effigies

and house slabs, the roughly-carved heads and

figures being outside their houses and in the

palisades which surround their villages.

In the illustration (page 17) are shown four

heads. The top one is treated in a conventional

and bold manner, and was placed at the top of a

house gable. The second head is far better work,

and more realistic, showing a finely-carved tattoo

pattern on the face. The mask was hung up as a

warning to trespassers implying the fate of such.

This specimen was brought to England by the late

Sir George Grey, and is now in the British Museum.

The small head (No. 3) is an example of simple,

bold carving, and is that of a little deity supposed to

preside over fishing expeditions ; the expression is

one of incredulity.

The fourth figure is ot a class that is generally

historic, being the effigy of an ancestor, and

judging by the moko (face tattooing) of some

important man. There was evidently some effort

on the part of the artist to make this family portrait

of pleasant expression but as a triumph of realistic

beauty it is a failure Tattooing is shown on the

deltoid muscles and the thighs.

Much attention was paid to the decoration of

what are known as feather boxes. When the Maori

was not wearing in his hair the sacred huai

feathers—which are greatly prized among them—

they were carefully preserved in these boxes,

called by them "papa whakiro." On these boxes

is found the most elaborate ornament, composed

of human figures and curves, with many shell discs

set in among the carving. These boxes are generally

cut from a solid piece of hard dark wood. All the

outer surfaces were ornamented.

The illustration on page 16 is of a fine specimen

of such work, and is to be seen in the British

Museum. The elaborately carved hand club shown

on page 19 is a curious combination of ornamental

designs of human figures, scrolls and curves : the

large head suggests that of a bird, but is probably

a very debased form of human head, the eye,

eyebrow, nose, and teeth being shown.

The knife (page 20), with a cutting edge com-

posed of a series of shark's teeth, is said to have

been used for killing human victims for sacrifice.