Garden-Making

naught, for he has made

that the whole which

should only be the part.

The perfect art may pre-

suppose the perfect culture

and make use of it, but it

must be for purposes out-

side the scientific perfec-

tion of growth. And so

with specimen trees and

evergreen shrubs, however

shapely may be the indi-

viduals, it does not follow

that the collection will be

sightly. The undisciplined

dotting of well-grown coni-

fers has ruined many a fair

garden lawn, and turned its

sunny spaciousness into the

aimlessness of a scrubby

wood.

So the art ot the

garden-maker is not con-

ditioned by scientific or

perfect growth, any more

than it is by the notions

of the landscape painter,

or by the formlessness of

Nature's wilderness. Its

one practical condition is

that of enclosure, the ac-

ceptation of the canvas

upon which the. artist can

exhibit himself. Here,

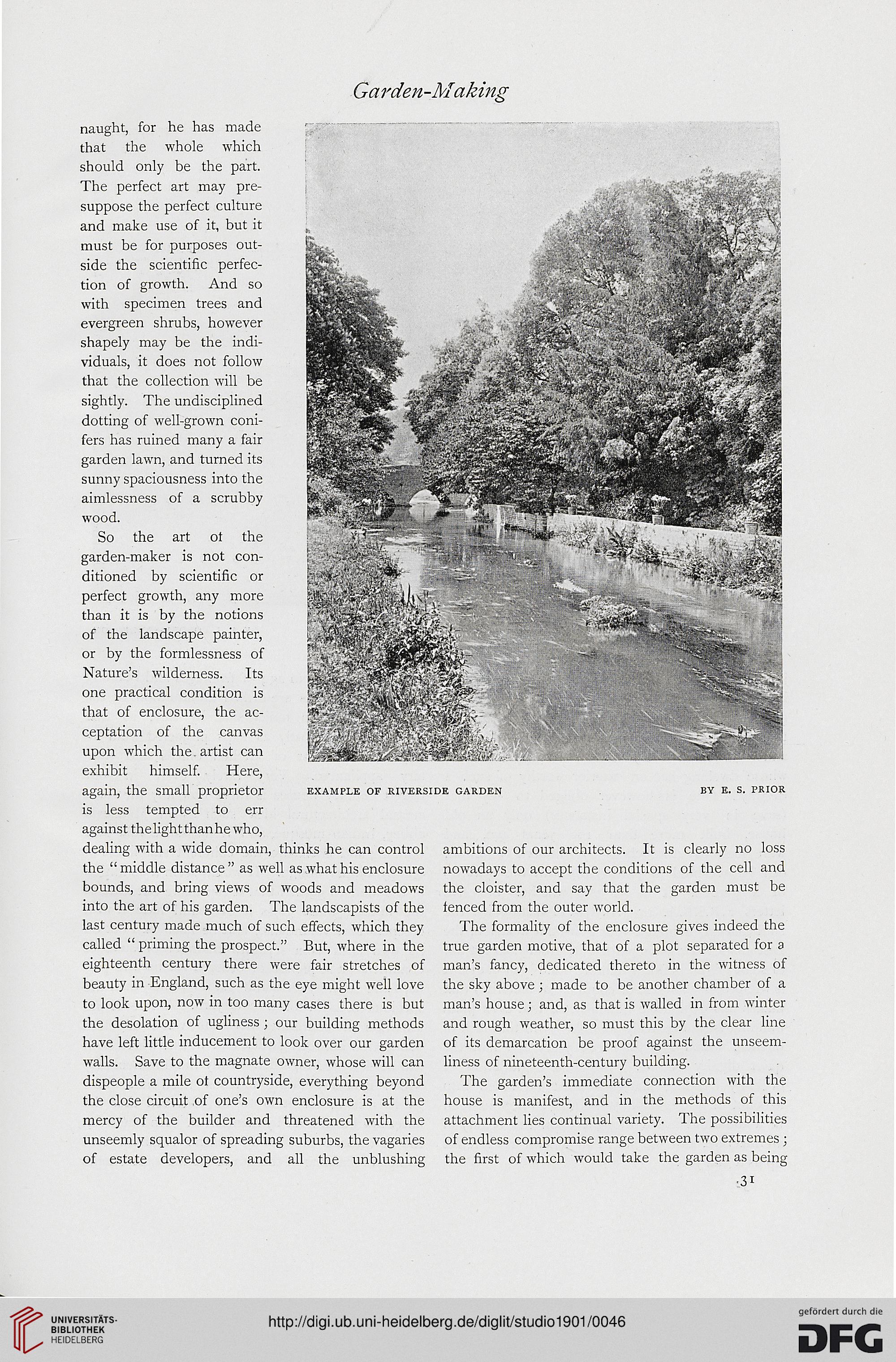

again, the small proprietor example of riverside garden by e. s. prior

is less tempted to err

against thelightthanhe who,

dealing with a wide domain, thinks he can control ambitions of our architects. It is clearly no loss

the "middle distance" as well as what his enclosure nowadays to accept the conditions of the cell and

bounds, and bring views of woods and meadows the cloister, and say that the garden must be

into the art of his garden. The landscapists of the fenced from the outer world.

last century made much of such effects, which they The formality of the enclosure gives indeed the

called " priming the prospect." But, where in the true garden motive, that of a plot separated for a

eighteenth century there were fair stretches of man's fancy, dedicated thereto in the witness of

beauty in England, such as the eye might well love the sky above ; made to be another chamber of a

to look upon, now in too many cases there is but man's house; and, as that is walled in from winter

the desolation of ugliness ; our building methods and rough weather, so must this by the clear line

have left little inducement to look over our garden of its demarcation be proof against the unseem-

walls. Save to the magnate owner, whose will can liness of nineteenth-century building,

dispeople a mile ot countryside, everything beyond The garden's immediate connection with the

the close circuit of one's own enclosure is at the house is manifest, and in the methods of this

mercy of the builder and threatened with the attachment lies continual variety. The possibilities

unseemly squalor of spreading suburbs, the vagaries of endless compromise range between two extremes ;

of estate developers, and all the unblushing the first of which would take the garden as being

3i

naught, for he has made

that the whole which

should only be the part.

The perfect art may pre-

suppose the perfect culture

and make use of it, but it

must be for purposes out-

side the scientific perfec-

tion of growth. And so

with specimen trees and

evergreen shrubs, however

shapely may be the indi-

viduals, it does not follow

that the collection will be

sightly. The undisciplined

dotting of well-grown coni-

fers has ruined many a fair

garden lawn, and turned its

sunny spaciousness into the

aimlessness of a scrubby

wood.

So the art ot the

garden-maker is not con-

ditioned by scientific or

perfect growth, any more

than it is by the notions

of the landscape painter,

or by the formlessness of

Nature's wilderness. Its

one practical condition is

that of enclosure, the ac-

ceptation of the canvas

upon which the. artist can

exhibit himself. Here,

again, the small proprietor example of riverside garden by e. s. prior

is less tempted to err

against thelightthanhe who,

dealing with a wide domain, thinks he can control ambitions of our architects. It is clearly no loss

the "middle distance" as well as what his enclosure nowadays to accept the conditions of the cell and

bounds, and bring views of woods and meadows the cloister, and say that the garden must be

into the art of his garden. The landscapists of the fenced from the outer world.

last century made much of such effects, which they The formality of the enclosure gives indeed the

called " priming the prospect." But, where in the true garden motive, that of a plot separated for a

eighteenth century there were fair stretches of man's fancy, dedicated thereto in the witness of

beauty in England, such as the eye might well love the sky above ; made to be another chamber of a

to look upon, now in too many cases there is but man's house; and, as that is walled in from winter

the desolation of ugliness ; our building methods and rough weather, so must this by the clear line

have left little inducement to look over our garden of its demarcation be proof against the unseem-

walls. Save to the magnate owner, whose will can liness of nineteenth-century building,

dispeople a mile ot countryside, everything beyond The garden's immediate connection with the

the close circuit of one's own enclosure is at the house is manifest, and in the methods of this

mercy of the builder and threatened with the attachment lies continual variety. The possibilities

unseemly squalor of spreading suburbs, the vagaries of endless compromise range between two extremes ;

of estate developers, and all the unblushing the first of which would take the garden as being

3i