Garden-Making

of endless craft. The field is as wide as the

canvas of the painter for light and shade, form and

colour, texture and style, mass and proportion,

which are the materials of garden design.

Also in the maintenance and stocking of the

garden as in its laying out, lies a pure art, leaning

neither on the associations of literary expression

nor on any dexterities of imitative realism. Its

strength is in its own true realism, in its partnership

with the great forces of the universe. Gardening,

of all the arts, has these forces most conveniently

at hand ready to be summoned to do its will.

But falsely conjured they will come only to spoil

and destroy : for it is in response to sense and

feeling that Nature makes our gardens, to man's

sense of what is order and fitness, to man's

feeling for the beautiful, which is the inherited

perception of this same order and fitness, as

witnessed by generations of ancestors in the course

of the universe.

Thus gardening can only be natural when it has that

formality which implies the mastery of " Nature's "

forms, and says distinctly, So far shall growth go to

my bidding, and here it shall be stayed. The

answer is complete to those who complain of the

clipping of a tree in a garden as a " perversion Oi

Nature." If you cut grass, because, when so cut,

Nature gives its growth a neatness and an order

which man thinks fitting, why not for the same end

cut your trees and shrubs ? If paths are to be kept

and beds to be weeded, why must not trees be

shaped and trimmed ? If the apple be pruned for

its purpose of fruitage, why not the yew for its

purpose of shapeliness ? And it is to be observed

that besides weak logic, there is a perverted in-

stinct of sentimentality lying at the back of the

rejection of order in the garden; in the craving

after irregular shapes and untidy growths. The

garden idea naturally associates itself in man's

mind with smooth lawns and with trimmed shrubs,

because for long centuries such clearing meant

safety and home to him, while the wild wood

meant danger and distress. It is unnatural taste

and contrary to man's hereditary ideas of beauty to

create the picturesqueness of untended growth

about his house. In fact the ridicule of the formal

garden is a highly wrought squeamishness, that is

merely capricious in its likes and dislikes, and in

its selection of what it calls graceful form in

"Nature," is as eclectic as any Dutchman.

But though directed to no futile imitation ot

heaths and coppices, yet the stocking and main-

tenance of the English garden should be on the

native lines. However avowed its art, it does not

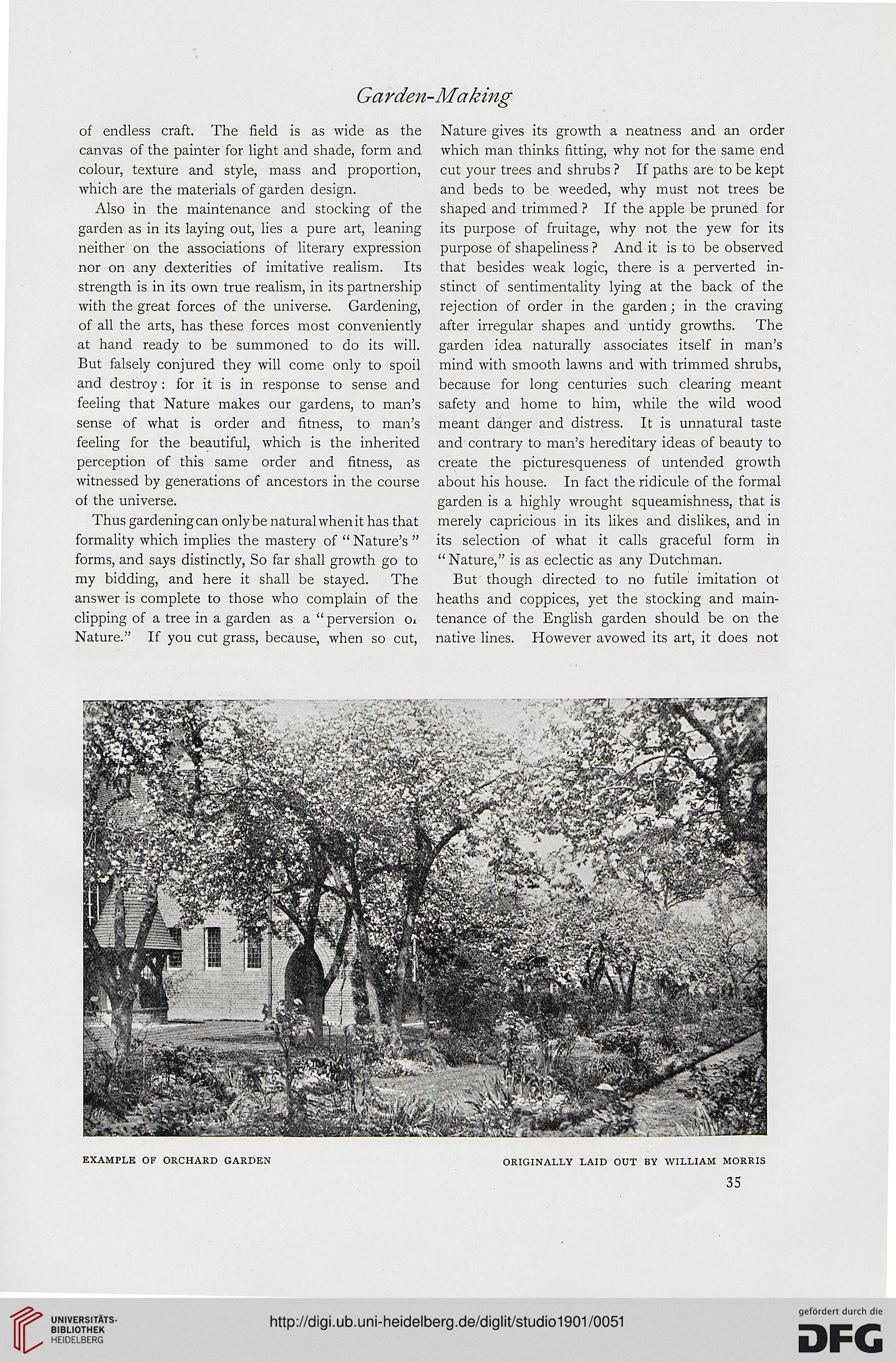

EXAMPLE OF ORCHARD GARDEN

ORIGINALLY LAID OUT BY WILLIAM MORRIS

35

of endless craft. The field is as wide as the

canvas of the painter for light and shade, form and

colour, texture and style, mass and proportion,

which are the materials of garden design.

Also in the maintenance and stocking of the

garden as in its laying out, lies a pure art, leaning

neither on the associations of literary expression

nor on any dexterities of imitative realism. Its

strength is in its own true realism, in its partnership

with the great forces of the universe. Gardening,

of all the arts, has these forces most conveniently

at hand ready to be summoned to do its will.

But falsely conjured they will come only to spoil

and destroy : for it is in response to sense and

feeling that Nature makes our gardens, to man's

sense of what is order and fitness, to man's

feeling for the beautiful, which is the inherited

perception of this same order and fitness, as

witnessed by generations of ancestors in the course

of the universe.

Thus gardening can only be natural when it has that

formality which implies the mastery of " Nature's "

forms, and says distinctly, So far shall growth go to

my bidding, and here it shall be stayed. The

answer is complete to those who complain of the

clipping of a tree in a garden as a " perversion Oi

Nature." If you cut grass, because, when so cut,

Nature gives its growth a neatness and an order

which man thinks fitting, why not for the same end

cut your trees and shrubs ? If paths are to be kept

and beds to be weeded, why must not trees be

shaped and trimmed ? If the apple be pruned for

its purpose of fruitage, why not the yew for its

purpose of shapeliness ? And it is to be observed

that besides weak logic, there is a perverted in-

stinct of sentimentality lying at the back of the

rejection of order in the garden; in the craving

after irregular shapes and untidy growths. The

garden idea naturally associates itself in man's

mind with smooth lawns and with trimmed shrubs,

because for long centuries such clearing meant

safety and home to him, while the wild wood

meant danger and distress. It is unnatural taste

and contrary to man's hereditary ideas of beauty to

create the picturesqueness of untended growth

about his house. In fact the ridicule of the formal

garden is a highly wrought squeamishness, that is

merely capricious in its likes and dislikes, and in

its selection of what it calls graceful form in

"Nature," is as eclectic as any Dutchman.

But though directed to no futile imitation ot

heaths and coppices, yet the stocking and main-

tenance of the English garden should be on the

native lines. However avowed its art, it does not

EXAMPLE OF ORCHARD GARDEN

ORIGINALLY LAID OUT BY WILLIAM MORRIS

35