77^ 77^ zj/, 77S'.^7.

and the two, finding they had much in sympathy,

painted a couple of pictures together, Z%g ZVzzM'y and

ZXg 272 2l& ^rzy?. But even before both were

completed, the artists were going different ways,

were developing on diverse lines, and so the

artistic partnership was short-lived. The large

canvas—it is some six feet square—called ZXg

Z?7*2222&, is a curiously interesting.

It was in 1893 that Henry stayed in Japan, a

stay that was to have momentous results on his

art both as a decorator and a portrait painter. He

found himself a visitor to a highly cultured race;

a race of artists who had evolved in their isola-

tion an art alien from, but as complete as,

that of the West. He was quick to observe the

Japanese sense of colour; he saw that their finest

things were almost monochromes, subtly and

infinitely varied schemes of tertiaries and sub-

tertiaries, with notes of pure colour used as

sparingly and as effectively as jewels. And this

artistic convention—the result ot centuries of

elimination of the vulgar and the meretricious—

appealed at once to Henry as delightful, beautiful,

and true. There is no doubt that the use of pure

colour, thus sparsely employed amid a delicate

environment, results in an effect of preciousness ;

and, carrying this idea a step farther, Henry

applied it to portraiture. What should be the

most precious thing in a portrait? Undoubtedly

the face of the sitter. There the interest of the

picture is focussed, there the artist- has most to

express, there he succeeds or he fails; and no dis-

traction of extraneous details, or emphasis of

colour elsewhere on the canvas, should be per-

mitted to interfere with the aspect of beauty or of

character in the countenance depicted. Henry

does not for a moment claim to have been the first

to feel this. Whistler, Rembrandt, and Velasquez,

to name no others, have worked along similar lines,

treating the face as the jewel of the composition,

the rest being but set-

ting ; but it was the art of

Japan that helped him

to observe the analogy, to

formulate the idea, and to

put it into practice.

But before passing to

Henry's portraits, allusion

must be made to one of

the most interesting and

most characteristic phases

of his art, which is

exemplified in such pic-

tures as These

canvases are frankly and

beautifully decorative; they

are works in which the

artist seeks to express the

sentiment of his subject,

not by inventing a story

to depict, but by the

arrangement of colour and

line; they are pictures

which exist simply as lovely

things. For a short time

the art of Rossetti appealed

to George Henry, at any

rate so far as his richness

of colour and power of

sumptuously decorative

treatment are concerned.

But this was modified

by what he learnt in

Japan; and while in the

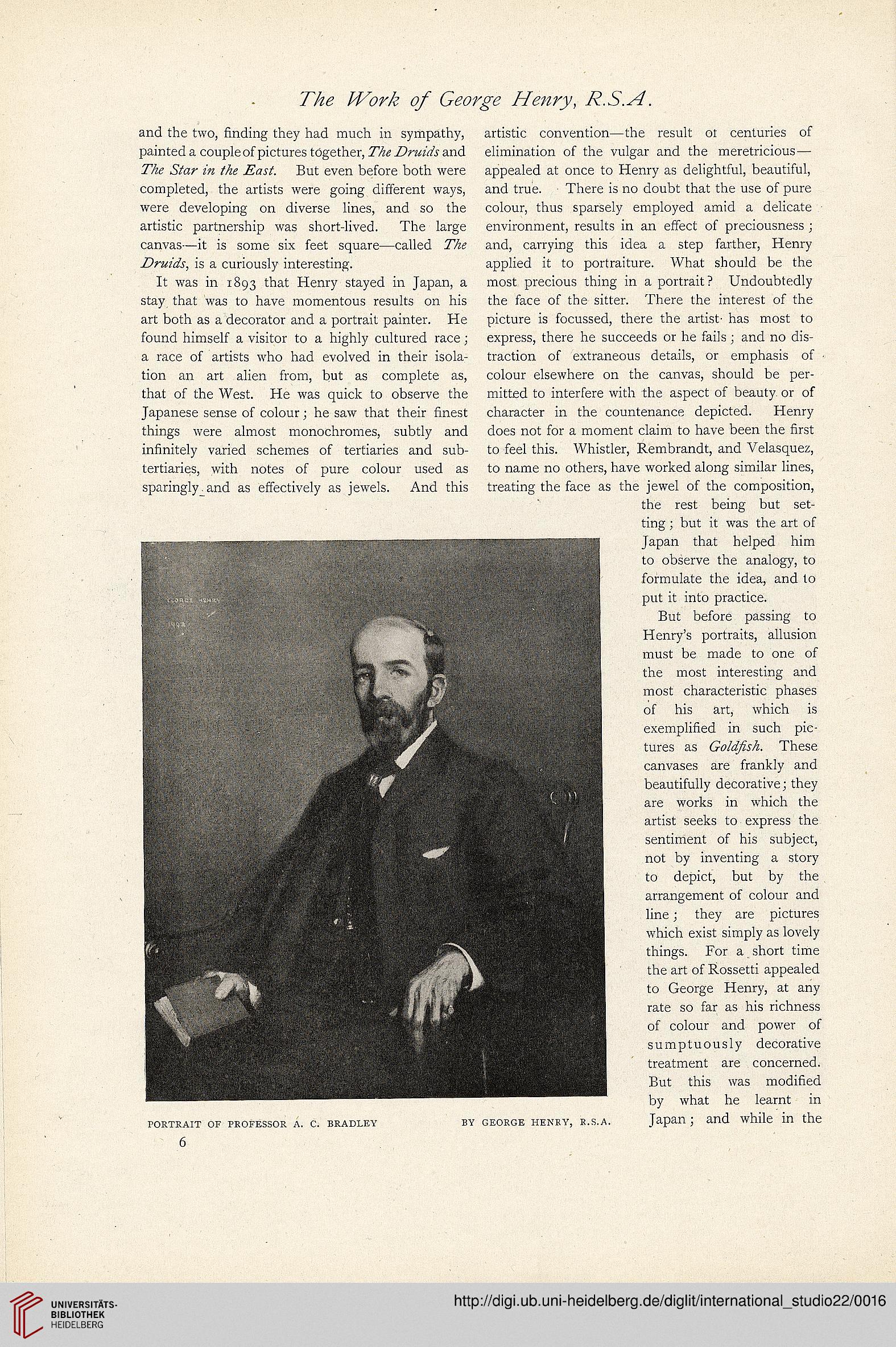

PORTRAtT OF PROFESSOR A. C. BRADLEY BY GEORGE HENRY, R.S.A.

and the two, finding they had much in sympathy,

painted a couple of pictures together, Z%g ZVzzM'y and

ZXg 272 2l& ^rzy?. But even before both were

completed, the artists were going different ways,

were developing on diverse lines, and so the

artistic partnership was short-lived. The large

canvas—it is some six feet square—called ZXg

Z?7*2222&, is a curiously interesting.

It was in 1893 that Henry stayed in Japan, a

stay that was to have momentous results on his

art both as a decorator and a portrait painter. He

found himself a visitor to a highly cultured race;

a race of artists who had evolved in their isola-

tion an art alien from, but as complete as,

that of the West. He was quick to observe the

Japanese sense of colour; he saw that their finest

things were almost monochromes, subtly and

infinitely varied schemes of tertiaries and sub-

tertiaries, with notes of pure colour used as

sparingly and as effectively as jewels. And this

artistic convention—the result ot centuries of

elimination of the vulgar and the meretricious—

appealed at once to Henry as delightful, beautiful,

and true. There is no doubt that the use of pure

colour, thus sparsely employed amid a delicate

environment, results in an effect of preciousness ;

and, carrying this idea a step farther, Henry

applied it to portraiture. What should be the

most precious thing in a portrait? Undoubtedly

the face of the sitter. There the interest of the

picture is focussed, there the artist- has most to

express, there he succeeds or he fails; and no dis-

traction of extraneous details, or emphasis of

colour elsewhere on the canvas, should be per-

mitted to interfere with the aspect of beauty or of

character in the countenance depicted. Henry

does not for a moment claim to have been the first

to feel this. Whistler, Rembrandt, and Velasquez,

to name no others, have worked along similar lines,

treating the face as the jewel of the composition,

the rest being but set-

ting ; but it was the art of

Japan that helped him

to observe the analogy, to

formulate the idea, and to

put it into practice.

But before passing to

Henry's portraits, allusion

must be made to one of

the most interesting and

most characteristic phases

of his art, which is

exemplified in such pic-

tures as These

canvases are frankly and

beautifully decorative; they

are works in which the

artist seeks to express the

sentiment of his subject,

not by inventing a story

to depict, but by the

arrangement of colour and

line; they are pictures

which exist simply as lovely

things. For a short time

the art of Rossetti appealed

to George Henry, at any

rate so far as his richness

of colour and power of

sumptuously decorative

treatment are concerned.

But this was modified

by what he learnt in

Japan; and while in the

PORTRAtT OF PROFESSOR A. C. BRADLEY BY GEORGE HENRY, R.S.A.