The JVork of Ernest Newton

the letter. Probably one of the most severe tests

that can be applied to any manner is whether it is

strong enough to stand the supreme flattery of

imitation. If it can, it deserves to be called a

" style j " if it cannot, it stands revealed as a mere

mannerism, that has but an accidental charm

which is rapidly diminished by every attempted

paraphrase. To copy literally and exactly the un-

related details of any style, and serve up the

mixture as an original design, is a secret of Punchi-

nello. The jerry builder will offer you a hideous

atrocity, whereof every window, every door, every

gable, every cornice, is a garbled replica of the

details of a master's work; as one might take

casts from masterpieces of the sculptor's art, a torso

here, a head there, arms from another, and legs

from a fourth, and produce not another master-

piece, but a monster. The parts may be more or

less right; the whole is absolutely wrong. Now, the

whole is greater than its parts, and a building must

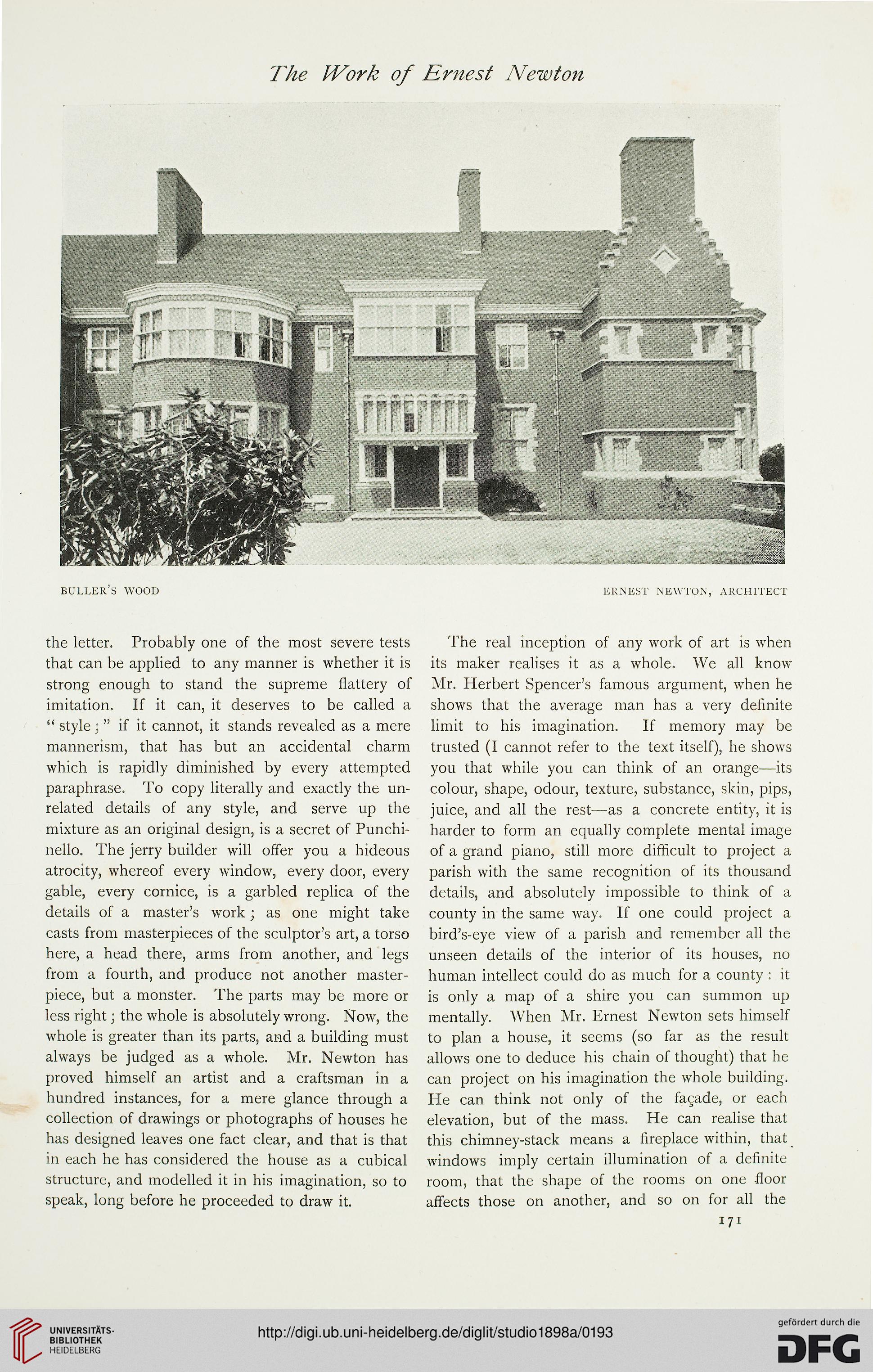

always be judged as a whole. Mr. Newton has

proved himself an artist and a craftsman in a

hundred instances, for a mere glance through a

collection of drawings or photographs of houses he

has designed leaves one fact clear, and that is that

in each he has considered the house as a cubical

structure, and modelled it in his imagination, so to

speak, long before he proceeded to draw it.

The real inception of any work of art is when

its maker realises it as a whole. We all know

Mr. Herbert Spencer's famous argument, when he

shows that the average man has a very definite

limit to his imagination. If memory may be

trusted (I cannot refer to the text itself), he shows

you that while you can think of an orange—its

colour, shape, odour, texture, substance, skin, pips,

juice, and all the rest—as a concrete entity, it is

harder to form an equally complete mental image

of a grand piano, still more difficult to project a

parish with the same recognition of its thousand

details, and absolutely impossible to think of a

county in the same way. If one could project a

bird's-eye view of a parish and remember all the

unseen details of the interior of its houses, no

human intellect could do as much for a county : it

is only a map of a shire you can summon up

mentally. When Mr. Ernest Newton sets himself

to plan a house, it seems (so far as the result

allows one to deduce his chain of thought) that he

can project on his imagination the whole building.

He can think not only of the facade, or each

elevation, but of the mass. He can realise that

this chimney-stack means a fireplace within, that

windows imply certain illumination of a definite

room, that the shape of the rooms on one floor

affects those on another, and so on for all the

171

the letter. Probably one of the most severe tests

that can be applied to any manner is whether it is

strong enough to stand the supreme flattery of

imitation. If it can, it deserves to be called a

" style j " if it cannot, it stands revealed as a mere

mannerism, that has but an accidental charm

which is rapidly diminished by every attempted

paraphrase. To copy literally and exactly the un-

related details of any style, and serve up the

mixture as an original design, is a secret of Punchi-

nello. The jerry builder will offer you a hideous

atrocity, whereof every window, every door, every

gable, every cornice, is a garbled replica of the

details of a master's work; as one might take

casts from masterpieces of the sculptor's art, a torso

here, a head there, arms from another, and legs

from a fourth, and produce not another master-

piece, but a monster. The parts may be more or

less right; the whole is absolutely wrong. Now, the

whole is greater than its parts, and a building must

always be judged as a whole. Mr. Newton has

proved himself an artist and a craftsman in a

hundred instances, for a mere glance through a

collection of drawings or photographs of houses he

has designed leaves one fact clear, and that is that

in each he has considered the house as a cubical

structure, and modelled it in his imagination, so to

speak, long before he proceeded to draw it.

The real inception of any work of art is when

its maker realises it as a whole. We all know

Mr. Herbert Spencer's famous argument, when he

shows that the average man has a very definite

limit to his imagination. If memory may be

trusted (I cannot refer to the text itself), he shows

you that while you can think of an orange—its

colour, shape, odour, texture, substance, skin, pips,

juice, and all the rest—as a concrete entity, it is

harder to form an equally complete mental image

of a grand piano, still more difficult to project a

parish with the same recognition of its thousand

details, and absolutely impossible to think of a

county in the same way. If one could project a

bird's-eye view of a parish and remember all the

unseen details of the interior of its houses, no

human intellect could do as much for a county : it

is only a map of a shire you can summon up

mentally. When Mr. Ernest Newton sets himself

to plan a house, it seems (so far as the result

allows one to deduce his chain of thought) that he

can project on his imagination the whole building.

He can think not only of the facade, or each

elevation, but of the mass. He can realise that

this chimney-stack means a fireplace within, that

windows imply certain illumination of a definite

room, that the shape of the rooms on one floor

affects those on another, and so on for all the

171