77/r I fork of Ernest Newton

detail reconsidered anew. Hut the simile is mot

quite happy, for here it is a certain austerity and

stern attempt to repress mere ornament, which

gives the New Queen Anne (as it was first called)

its real claim to be taken seriously, whereas English

Gothic grew more and more ornate, until it was

smothered by its superfluous decoration.

The reason for the renewed vitality imparted to

architecture to-day is not far to seek. As Mr.

Ernest Newton wrote in his contribution to a

notable volume (" Architecture a Profession or an

Of practical building if funds allow, but is

either present or absent from the first."' That is

the text of his writings, and it is also the test

whereby one may judge his work. And because

it is so, the difficulty of writing an appreciation

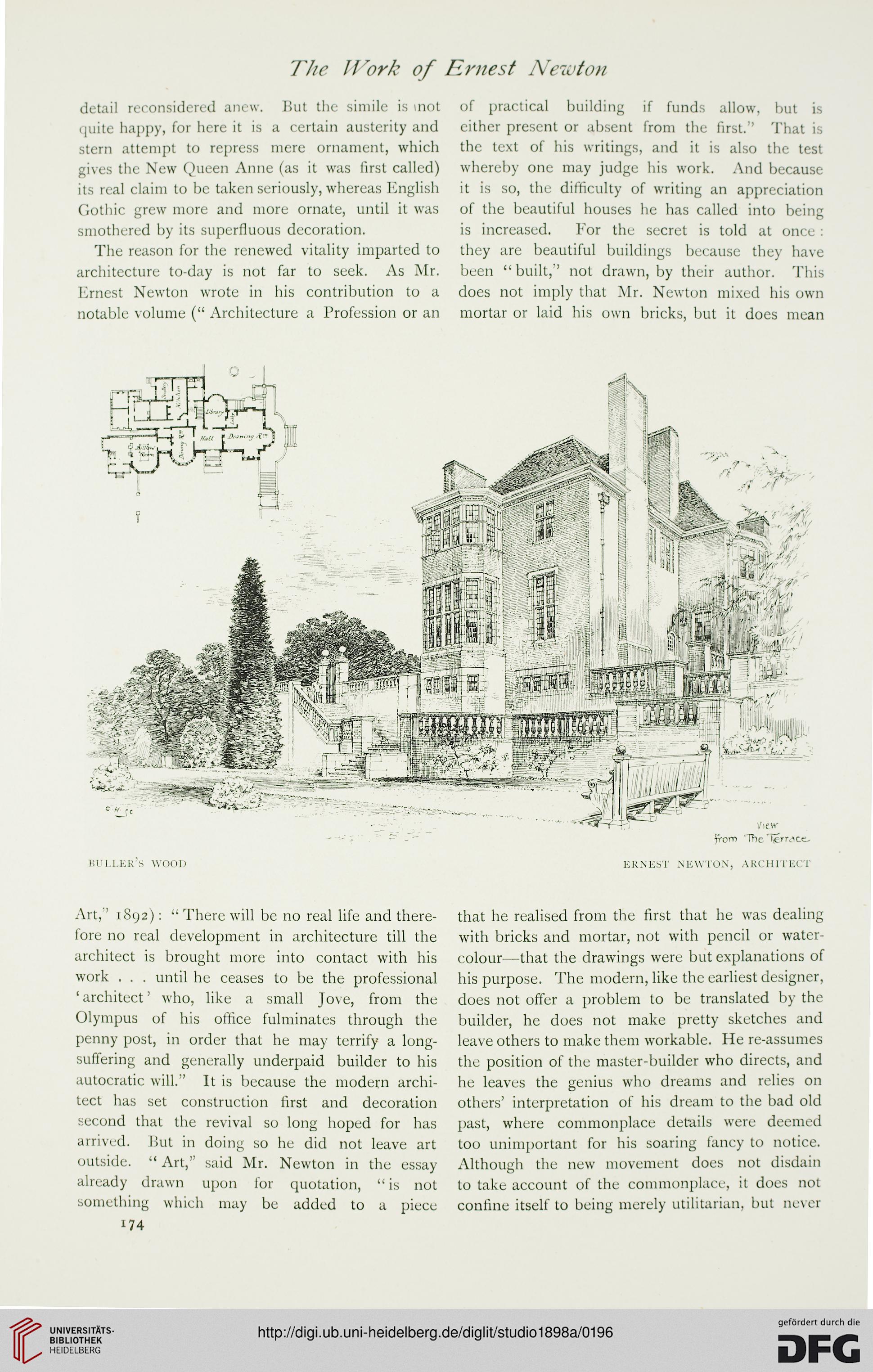

of the beautiful houses he has called into being

is increased. For the secret is told at once :

they are beautiful buildings because they have

been "built,"' not drawn, by their author. This

does not imply that Mr. Newton mixed his own

mortar or laid his own bricks, but it does mean

Art,' 1892): " There will be no real life and there-

fore no real development in architecture till the

architect is brought more into contact with his

work . . . until he ceases to be the professional

'architect' who, like a small Jove, from the

Olympus of his office fulminates through the

penny post, in order that he may terrify a long-

suffering and generally underpaid builder to his

autocratic will."' It is because the modern archi-

tect has set construction first and decoration

second that the revival so long hoped for has

arrived, but in doing so he did not leave art

outside. " Art," said Mr. Newton in the essay

already drawn upon for quotation, ki is not

something which may be added to a piece

174

that he realised from the first that he was dealing

with bricks and mortar, not with pencil or water-

colour—that the drawings were but explanations of

his purpose. The modern, like the earliest designer,

does not offer a problem to be translated by the

builder, he does not make pretty sketches and

leave others to make them workable. He re-assumes

the position of the master-builder who directs, and

he leaves the genius who dreams and relies on

others' interpretation of his dream to the bad old

past, where commonplace derails were deemed

too unimportant for his soaring fancy to notice.

Although the new movement does not disdain

to take account of the commonplace, it does not

confine itself to being merely utilitarian, but never

detail reconsidered anew. Hut the simile is mot

quite happy, for here it is a certain austerity and

stern attempt to repress mere ornament, which

gives the New Queen Anne (as it was first called)

its real claim to be taken seriously, whereas English

Gothic grew more and more ornate, until it was

smothered by its superfluous decoration.

The reason for the renewed vitality imparted to

architecture to-day is not far to seek. As Mr.

Ernest Newton wrote in his contribution to a

notable volume (" Architecture a Profession or an

Of practical building if funds allow, but is

either present or absent from the first."' That is

the text of his writings, and it is also the test

whereby one may judge his work. And because

it is so, the difficulty of writing an appreciation

of the beautiful houses he has called into being

is increased. For the secret is told at once :

they are beautiful buildings because they have

been "built,"' not drawn, by their author. This

does not imply that Mr. Newton mixed his own

mortar or laid his own bricks, but it does mean

Art,' 1892): " There will be no real life and there-

fore no real development in architecture till the

architect is brought more into contact with his

work . . . until he ceases to be the professional

'architect' who, like a small Jove, from the

Olympus of his office fulminates through the

penny post, in order that he may terrify a long-

suffering and generally underpaid builder to his

autocratic will."' It is because the modern archi-

tect has set construction first and decoration

second that the revival so long hoped for has

arrived, but in doing so he did not leave art

outside. " Art," said Mr. Newton in the essay

already drawn upon for quotation, ki is not

something which may be added to a piece

174

that he realised from the first that he was dealing

with bricks and mortar, not with pencil or water-

colour—that the drawings were but explanations of

his purpose. The modern, like the earliest designer,

does not offer a problem to be translated by the

builder, he does not make pretty sketches and

leave others to make them workable. He re-assumes

the position of the master-builder who directs, and

he leaves the genius who dreams and relies on

others' interpretation of his dream to the bad old

past, where commonplace derails were deemed

too unimportant for his soaring fancy to notice.

Although the new movement does not disdain

to take account of the commonplace, it does not

confine itself to being merely utilitarian, but never