C. H. Shannons Lithographs

for the artist’s delight, and they are corrected

by the straight lines of the perpendicular mirror.

One feels that that mirror was placed there

for that reason, the best of artistic reasons,

and one hopes that Mr. Shannon put so many

screws on the smaller instrument and so few

on the large viol, not out of any knowledge of such

things, and he may have much, but because they

came thus under his hand, part of the picture as he

mentally foreshadowed it. It is obvious from this

drawing that the study of such things sometimes

tells, but for the moment it is to be believed that

their placing was instinctive, and as much a matter of

inspiration as the design of the drapery and the

balance given by the shadows thrown faintly on the

wall. Amendment and detail may follow his first

impulse, in rapid afterthoughts, but his drawings

half decided gestures are

arrested, their conversa-

tions are interrupted, and

their business ends for our

desire. Moving towards a

strange doorway, by the

light of an unfamiliar

lamp, they whispered of

strange things, or they

were going down to the

sea; they were playing with

little babies, bathing them

in cool stone baths when

the artist surprised them,

or they were listening

where the echoes of their

music died within the still-

ness of the room. In the

drawing called The Cellist

where the girls rest, with

instruments in their hands,

in white dresses folded

against the white wall, all

that the artist has delicately

hinted to our imagination

by a gift of which he is the

possessor, is carried un-

consciously to completion

by ourselves. We colourthe

hair of the languid girls, the

gold of their hair and the

brown violins; in the suave

lines of the robes we

are aware of texture as

though we touched the

folds with our hands.

Those lines came there

28

photographic restrictions, though often arriving

at the truest definition through its more elastic

and sensitive observation.

As a sonnet, just a few lines grouped to a spell of

music or to realise in expression a momentary mood,

so are these lithographs ; they are here for their own

sake, not insisting on any shape too much, not

asserting anything—simply flowers, having their

root in the obedience of hand to form and a

memory for form, and in an indefinite and beautiful

imagination. There is revealed to us by this art, if

only for a moment, how freighted are the hours with

beauty—and how indifferently we let them pass.

We are aware of figures coming and going, glowing

and fading under the artist’s hand; their thoughts

are turned inward to their own pleasures, and they

are on their way from a dream to a dream. Their

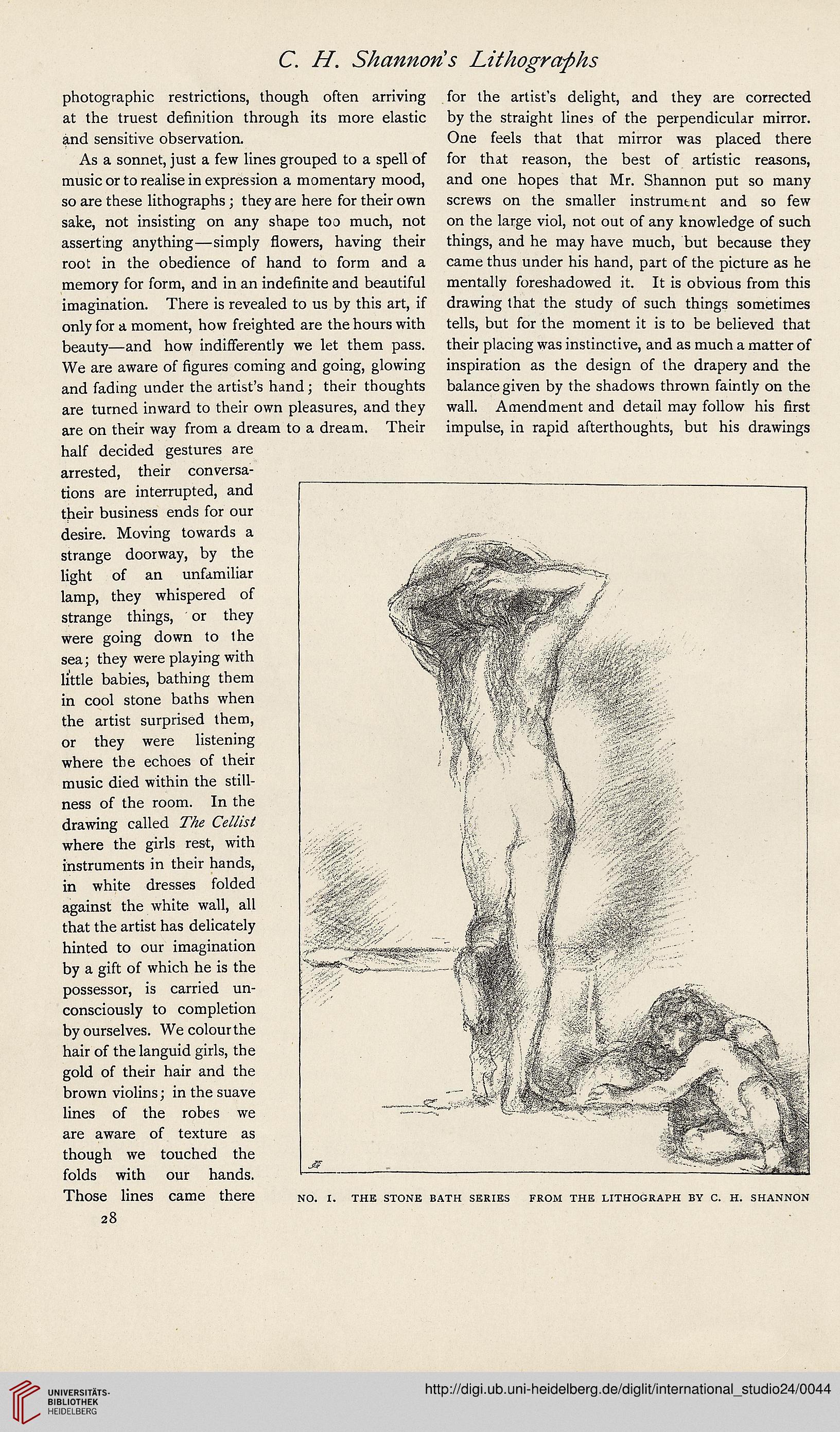

NO. I. THE STONE BATH SERIES FROM THE LITHOGRAPH BY C. H. SHANNON

for the artist’s delight, and they are corrected

by the straight lines of the perpendicular mirror.

One feels that that mirror was placed there

for that reason, the best of artistic reasons,

and one hopes that Mr. Shannon put so many

screws on the smaller instrument and so few

on the large viol, not out of any knowledge of such

things, and he may have much, but because they

came thus under his hand, part of the picture as he

mentally foreshadowed it. It is obvious from this

drawing that the study of such things sometimes

tells, but for the moment it is to be believed that

their placing was instinctive, and as much a matter of

inspiration as the design of the drapery and the

balance given by the shadows thrown faintly on the

wall. Amendment and detail may follow his first

impulse, in rapid afterthoughts, but his drawings

half decided gestures are

arrested, their conversa-

tions are interrupted, and

their business ends for our

desire. Moving towards a

strange doorway, by the

light of an unfamiliar

lamp, they whispered of

strange things, or they

were going down to the

sea; they were playing with

little babies, bathing them

in cool stone baths when

the artist surprised them,

or they were listening

where the echoes of their

music died within the still-

ness of the room. In the

drawing called The Cellist

where the girls rest, with

instruments in their hands,

in white dresses folded

against the white wall, all

that the artist has delicately

hinted to our imagination

by a gift of which he is the

possessor, is carried un-

consciously to completion

by ourselves. We colourthe

hair of the languid girls, the

gold of their hair and the

brown violins; in the suave

lines of the robes we

are aware of texture as

though we touched the

folds with our hands.

Those lines came there

28

photographic restrictions, though often arriving

at the truest definition through its more elastic

and sensitive observation.

As a sonnet, just a few lines grouped to a spell of

music or to realise in expression a momentary mood,

so are these lithographs ; they are here for their own

sake, not insisting on any shape too much, not

asserting anything—simply flowers, having their

root in the obedience of hand to form and a

memory for form, and in an indefinite and beautiful

imagination. There is revealed to us by this art, if

only for a moment, how freighted are the hours with

beauty—and how indifferently we let them pass.

We are aware of figures coming and going, glowing

and fading under the artist’s hand; their thoughts

are turned inward to their own pleasures, and they

are on their way from a dream to a dream. Their

NO. I. THE STONE BATH SERIES FROM THE LITHOGRAPH BY C. H. SHANNON