Constantin Mauiici

social reformers; her mission has happily nothing terically. It is a very different grief that Meunier

in common with Exeter Hall and the cant of shows us. The husband he keeps out of sight, and

humanitarianism. Vet we are told that (Jon- the wife, bending awkwardly forward, her arms

stantin Meunier is "a saviour of society," and that dangling weakly by her side, seems the Niobe of

his art is eminently fitted to make us all set about Toil, turned into bronze by the sudden horror of

the task of turning the collier into a man of means. the catastrophe.

That Meunier has been a true friend to the The noble reticence of feeling in this work, as

(-oilier I do not for a moment doubt. At the time in Ecce Homo, is not a Flemish quality as a rule,

when he began drawing his inspiration from the Perhaps it is the result of the artist's own sufferings.

Belgian Black Country, no laws of State regulated We meet with it again, as with the rest of Meunier's

the working of the mines. The coal trade was qualities, in another masterpiece in bronze, An Old

then, in Belgium, a horrible child-sweating industry, Colliery Horse, which I should describe on my

by which young girls were brutalised and lads de- own account, were it not that M. Octave Mirbeau

formed. All this M. Meunier painted; and his has made the pleasant task unnecessary. M. Mir-

pictures not only provoked remark, they stimulated beau's description has been thus done into English

reform. But the real point is this: that his methods by Miss Florence Simmonds:

were all honestly artistic \ they had no affinity with " How weary he is, this poor old colliery horse !

those which the late Mrs. Beecher

Stowe made so popular, when calling

attention to another and less de-

graded kind of " black " slavery. In

other words, M. Meunier has never

been a man with a mission—a Millet,

half-poet unwittingly, and wittingly

half-preacher. The ethical and

socialistic interests of his work,

about which so much nonsense has

been talked, owe their origin to an

impressive truthfulness to nature,

and not to a highly self-conscious

kind of humanitarian teaching.

Meunier understands the life of the

mining poor in Belgium; he works

because he has something to say,

and that something he gives expres-

sion to in a style all his own, rugged,

masculine, reticent, and filled with

an uncouth dignity and pathos.

Michel Angelo might have painted

thus if he had been at heart a

collier.

In Fire Damp, a bronze group in

the Brussels Museum, Constantin

Meunier has made real for us the

dazed terror of a collier's wife when

she first beholds her husband's dead

body. Here, indeed, is a subject to

make any inferior artist melo-drama-

tic. Guido Mazzoni, for instance,

who has left us some very curious

Good Friday religious dramas in

coloured clay, would have repre-

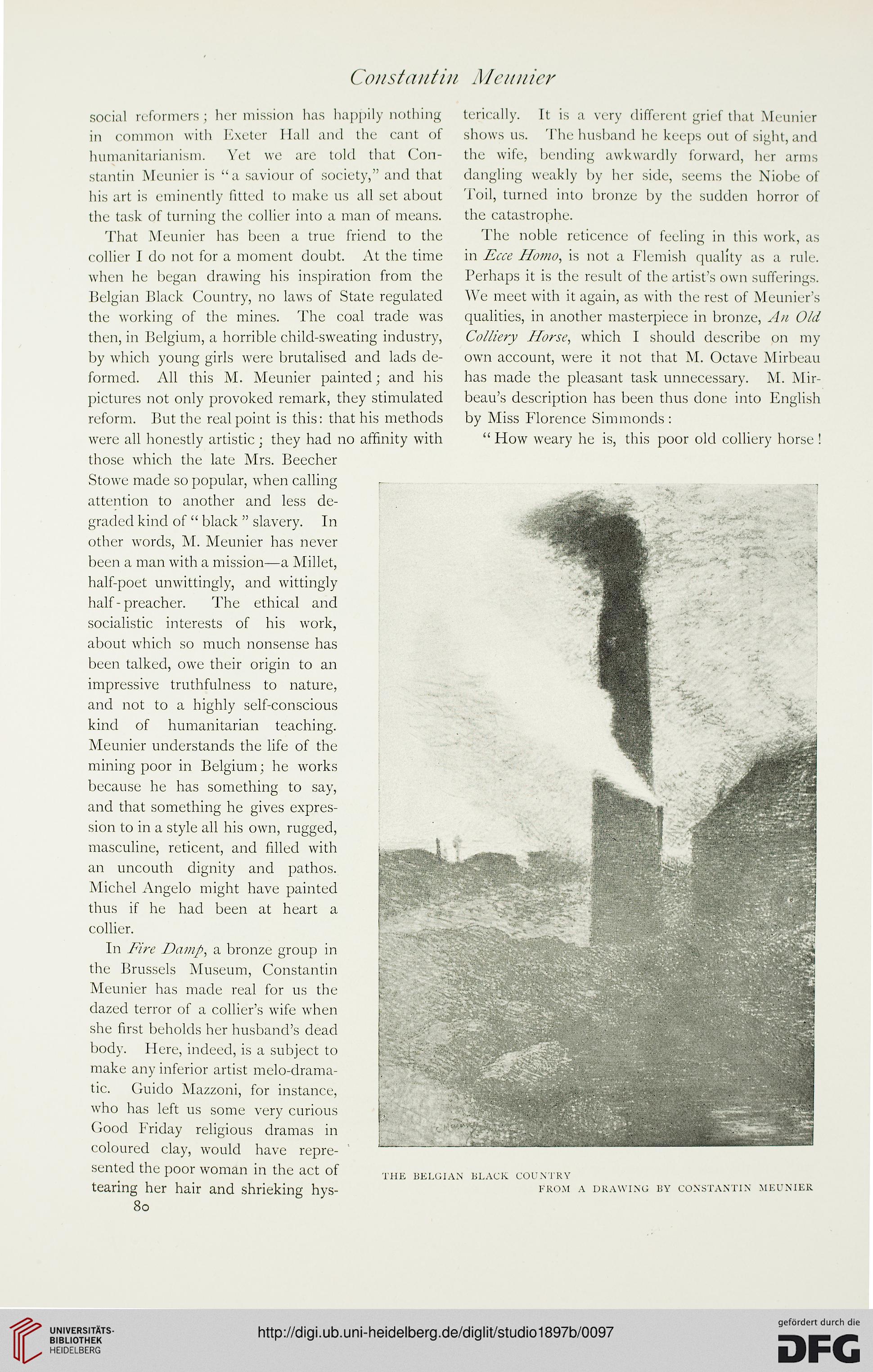

sented the poor woman in the act of the Belgian black country

tearing her hair and shrieking hys- from a drawing by constantin meunier

80

social reformers; her mission has happily nothing terically. It is a very different grief that Meunier

in common with Exeter Hall and the cant of shows us. The husband he keeps out of sight, and

humanitarianism. Vet we are told that (Jon- the wife, bending awkwardly forward, her arms

stantin Meunier is "a saviour of society," and that dangling weakly by her side, seems the Niobe of

his art is eminently fitted to make us all set about Toil, turned into bronze by the sudden horror of

the task of turning the collier into a man of means. the catastrophe.

That Meunier has been a true friend to the The noble reticence of feeling in this work, as

(-oilier I do not for a moment doubt. At the time in Ecce Homo, is not a Flemish quality as a rule,

when he began drawing his inspiration from the Perhaps it is the result of the artist's own sufferings.

Belgian Black Country, no laws of State regulated We meet with it again, as with the rest of Meunier's

the working of the mines. The coal trade was qualities, in another masterpiece in bronze, An Old

then, in Belgium, a horrible child-sweating industry, Colliery Horse, which I should describe on my

by which young girls were brutalised and lads de- own account, were it not that M. Octave Mirbeau

formed. All this M. Meunier painted; and his has made the pleasant task unnecessary. M. Mir-

pictures not only provoked remark, they stimulated beau's description has been thus done into English

reform. But the real point is this: that his methods by Miss Florence Simmonds:

were all honestly artistic \ they had no affinity with " How weary he is, this poor old colliery horse !

those which the late Mrs. Beecher

Stowe made so popular, when calling

attention to another and less de-

graded kind of " black " slavery. In

other words, M. Meunier has never

been a man with a mission—a Millet,

half-poet unwittingly, and wittingly

half-preacher. The ethical and

socialistic interests of his work,

about which so much nonsense has

been talked, owe their origin to an

impressive truthfulness to nature,

and not to a highly self-conscious

kind of humanitarian teaching.

Meunier understands the life of the

mining poor in Belgium; he works

because he has something to say,

and that something he gives expres-

sion to in a style all his own, rugged,

masculine, reticent, and filled with

an uncouth dignity and pathos.

Michel Angelo might have painted

thus if he had been at heart a

collier.

In Fire Damp, a bronze group in

the Brussels Museum, Constantin

Meunier has made real for us the

dazed terror of a collier's wife when

she first beholds her husband's dead

body. Here, indeed, is a subject to

make any inferior artist melo-drama-

tic. Guido Mazzoni, for instance,

who has left us some very curious

Good Friday religious dramas in

coloured clay, would have repre-

sented the poor woman in the act of the Belgian black country

tearing her hair and shrieking hys- from a drawing by constantin meunier

80