172

PlOTR Ł. GROTOWSKI

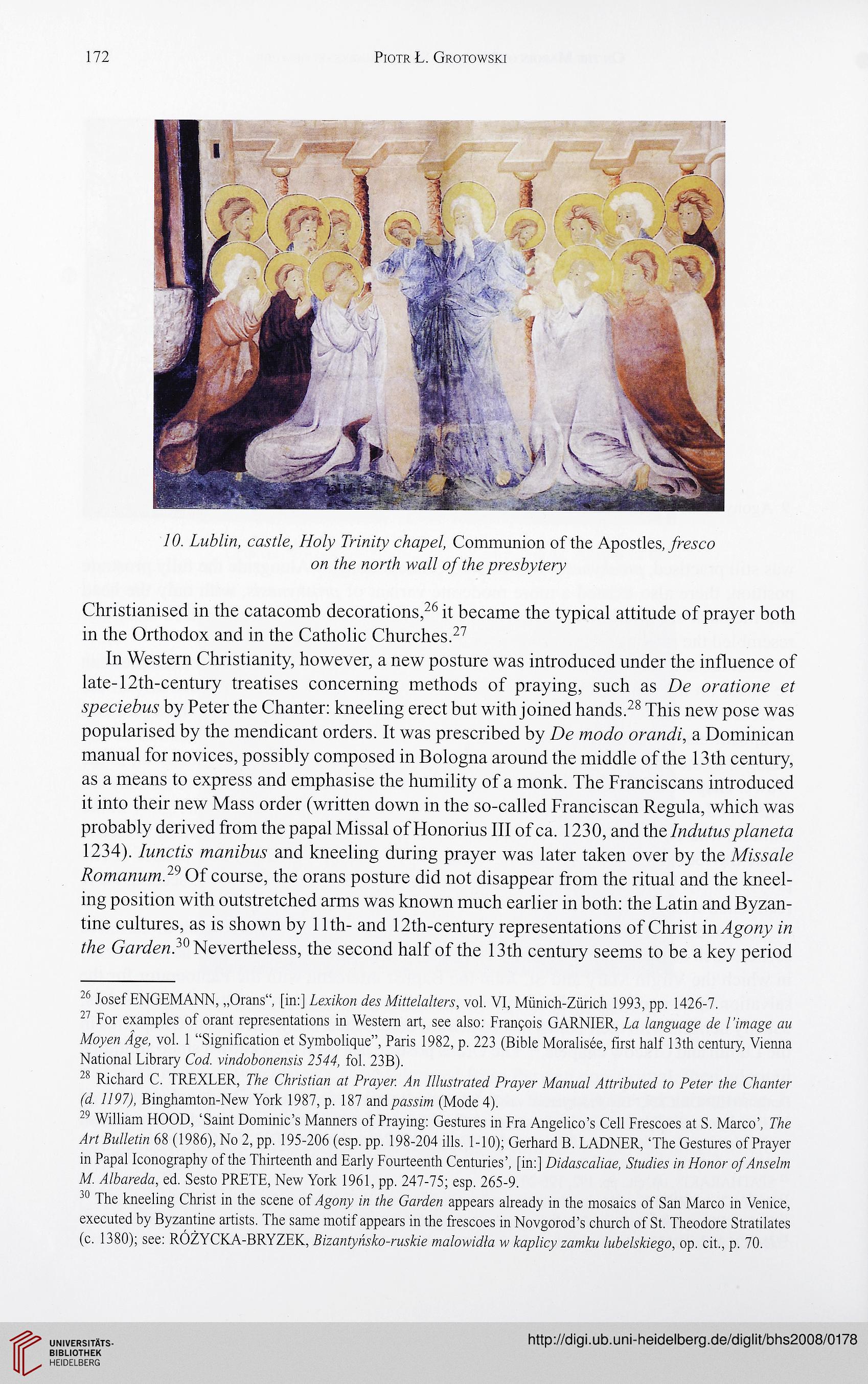

70. LzzA/zzz, erzv//e, Do/y Dzhz/y cAoye/, Communion of the Apostles, ypayco

ozz /Ae zzozvA uw// o/ /Ae yzv.s'Ay/o/y

Christianised in the catacomb decorations,^^ it became the typical attitude of prayer both

in the Orthodox and in the Catholic Churches.*^

In Western Christianity, however, a new posture was introduced under the influence of

late-12th-century treatises concerning methods of praying, such as De ozvz/zozzo e/

spec/gAzey by Peter the Chanter: kneeling erect but with joined hands.^ This new pose was

popularised by the mendicant orders. It was prescribed by De zzzoz/o eux?/?///, a Dominican

manual for novices, possibly composed in Bologna around the middle of the 13th century,

as a means to express and emphasise the humility of a monk. The Franciscans introduced

it into their new Mass order (written down in the so-called Franciscan Regula, which was

probably derived from the papal Missal of Honorius III of ca. 1230, and theZh/D/zeyy/ozzo/o

1234). /zzz/o/zN zrzoz/zAzz^ and kneeling during prayer was later taken over by the ADswo/o

/?0777<377M77z.^ Of course, the orans posture did not disappear from the ritual and the kneel-

ing position with outstretched arms was known much earlier in both: the Latin and Byzan-

tine cultures, as is shown by 11th- and 12th-century representations of Christ in Agoz/y zz?

/A<? GozDoz/T^ Nevertheless, the second half of the 13th century seems to be a key period

Josef ENGEMANN, „Orans", [in:] Agx/Aou <7gy A4ZZZg/a/Zgz*y, vol. VI, Münich-Zürich 1993, pp. 1426-7.

22 For examples of orant representations in Western art, see also: François GARNIER, Aa /angaagg & /7wagg aa

AAqygu Agg, vol. 1 "Signification et Symbolique", Paris 1982, p. 223 (Bible Moralisee, Erst half 13th century, Vienna

National Library Cor/. v/aAoAoagay/y 2344, fol. 23B).

2^ Richard C. TREXLER, 77?g C/aAZ/'aa at /Yayg/i Au A/a.sZraZgA Rraygr A4aaaa/ AzZn'AaZgA Zo PgZgr Z/?g CAaaZgr

D 7/97), Binghamton-New York 1987, p. 187 and /zayy/ui (Mode 4).

26 William HOOD, 'Saint Dominic's Manners of Praying: Gestures in Fra Angelico's Cell Frescoes at S. Marco', 77?g

Arz Aa//gZZu 68 (1986), No 2, pp. 195-206 (esp. pp. 198-204 ills. 1-10); Gerhard B. LADNER, 'The Gestures of Prayer

in Papal Iconography of the Thirteenth and Early Fourteenth Centuries', [in:] D/AaygaA'ag, AzaA/gy tu 77oaoz^

44. A/Aargr/a, ed. Sesto PRETE, New York 1961, pp. 247-75; esp. 265-9.

'6 The kneeling Christ in the scene of Agouy à? z/?g Gazr/ga appears already in the mosaics of San Marco in Venice,

executed by Byzantine artists. The same motif appears in the frescoes in Novgorod's church of St. Theodore Stratilates

(c. 1380); see: RÓŻYCKA-BRYZEK. A/zaaZyayAa-rayA/g /aa/oua'A/a w AapA'cy za/aAa /aAg/yA/ggo, op. cit., p. 70.

PlOTR Ł. GROTOWSKI

70. LzzA/zzz, erzv//e, Do/y Dzhz/y cAoye/, Communion of the Apostles, ypayco

ozz /Ae zzozvA uw// o/ /Ae yzv.s'Ay/o/y

Christianised in the catacomb decorations,^^ it became the typical attitude of prayer both

in the Orthodox and in the Catholic Churches.*^

In Western Christianity, however, a new posture was introduced under the influence of

late-12th-century treatises concerning methods of praying, such as De ozvz/zozzo e/

spec/gAzey by Peter the Chanter: kneeling erect but with joined hands.^ This new pose was

popularised by the mendicant orders. It was prescribed by De zzzoz/o eux?/?///, a Dominican

manual for novices, possibly composed in Bologna around the middle of the 13th century,

as a means to express and emphasise the humility of a monk. The Franciscans introduced

it into their new Mass order (written down in the so-called Franciscan Regula, which was

probably derived from the papal Missal of Honorius III of ca. 1230, and theZh/D/zeyy/ozzo/o

1234). /zzz/o/zN zrzoz/zAzz^ and kneeling during prayer was later taken over by the ADswo/o

/?0777<377M77z.^ Of course, the orans posture did not disappear from the ritual and the kneel-

ing position with outstretched arms was known much earlier in both: the Latin and Byzan-

tine cultures, as is shown by 11th- and 12th-century representations of Christ in Agoz/y zz?

/A<? GozDoz/T^ Nevertheless, the second half of the 13th century seems to be a key period

Josef ENGEMANN, „Orans", [in:] Agx/Aou <7gy A4ZZZg/a/Zgz*y, vol. VI, Münich-Zürich 1993, pp. 1426-7.

22 For examples of orant representations in Western art, see also: François GARNIER, Aa /angaagg & /7wagg aa

AAqygu Agg, vol. 1 "Signification et Symbolique", Paris 1982, p. 223 (Bible Moralisee, Erst half 13th century, Vienna

National Library Cor/. v/aAoAoagay/y 2344, fol. 23B).

2^ Richard C. TREXLER, 77?g C/aAZ/'aa at /Yayg/i Au A/a.sZraZgA Rraygr A4aaaa/ AzZn'AaZgA Zo PgZgr Z/?g CAaaZgr

D 7/97), Binghamton-New York 1987, p. 187 and /zayy/ui (Mode 4).

26 William HOOD, 'Saint Dominic's Manners of Praying: Gestures in Fra Angelico's Cell Frescoes at S. Marco', 77?g

Arz Aa//gZZu 68 (1986), No 2, pp. 195-206 (esp. pp. 198-204 ills. 1-10); Gerhard B. LADNER, 'The Gestures of Prayer

in Papal Iconography of the Thirteenth and Early Fourteenth Centuries', [in:] D/AaygaA'ag, AzaA/gy tu 77oaoz^

44. A/Aargr/a, ed. Sesto PRETE, New York 1961, pp. 247-75; esp. 265-9.

'6 The kneeling Christ in the scene of Agouy à? z/?g Gazr/ga appears already in the mosaics of San Marco in Venice,

executed by Byzantine artists. The same motif appears in the frescoes in Novgorod's church of St. Theodore Stratilates

(c. 1380); see: RÓŻYCKA-BRYZEK. A/zaaZyayAa-rayA/g /aa/oua'A/a w AapA'cy za/aAa /aAg/yA/ggo, op. cit., p. 70.