A. CUTLER, "PROBLEMS OF IVORY CARVING IN THE CHRISTIAN EAST (1ŻTH AND 13TH CENTURIES)" 28 1

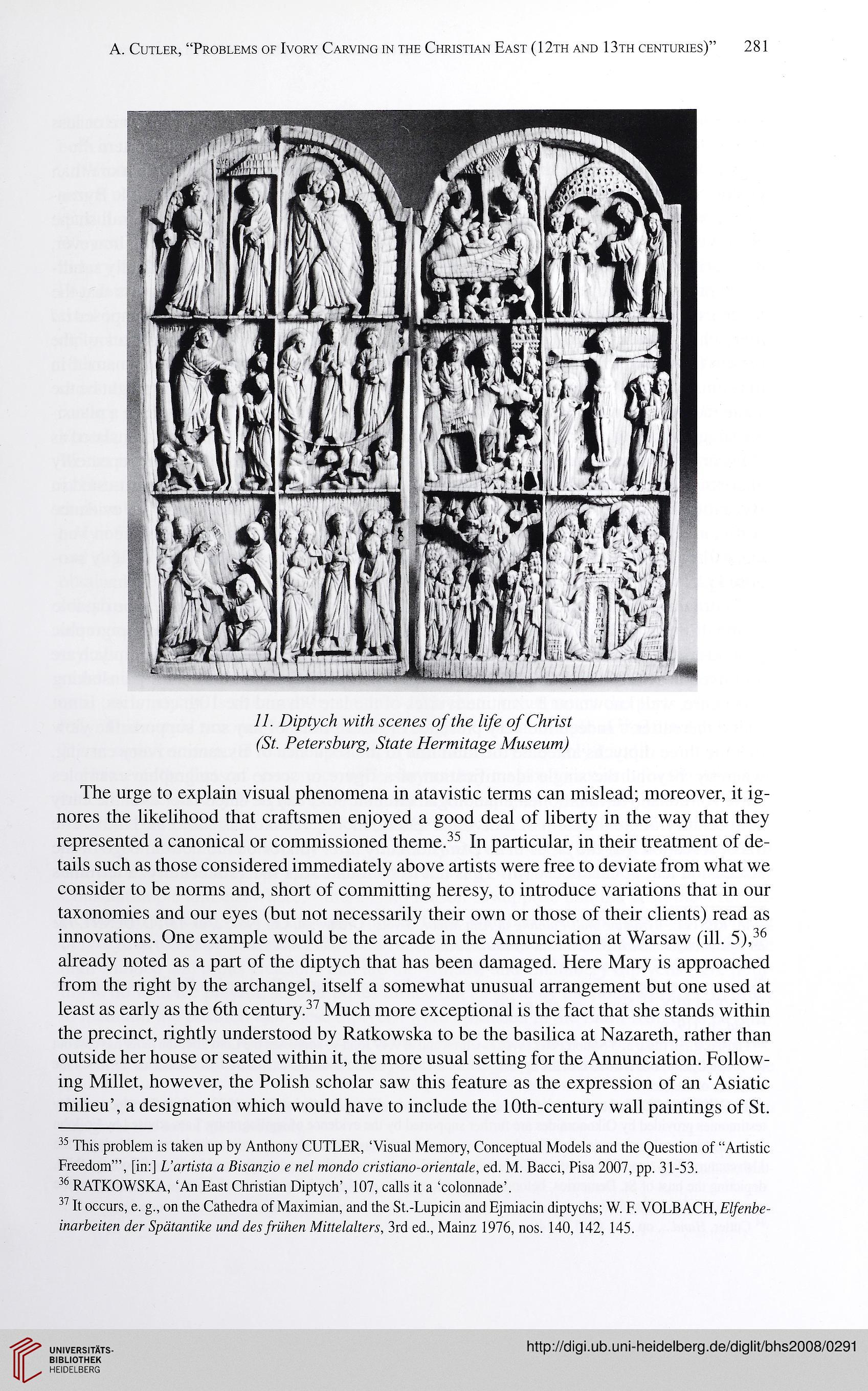

77. D/p7ycA wz'/A YCC/76A qA/Ac /i/e q/CArAf

(57. Pu/er.sAH/g, 5fa/c 7Vcrw//<rgc A7M,scMw)

The urge to explain visual phenomena in atavistic terms can mislead; moreover, it ig-

nores the likelihood that craftsmen enjoyed a good deal of liberty in the way that they

represented a canonical or commissioned theme.^ In particular, in their treatment of de-

tails such as those considered immediately above artists were free to deviate from what we

consider to be norms and, short of committing heresy, to introduce variations that in our

taxonomies and our eyes (but not necessarily their own or those of their clients) read as

innovations. One example would be the arcade in the Annunciation at Warsaw (ill. 5),^

already noted as a part of the diptych that has been damaged. Here Mary is approached

from the right by the archangel, itself a somewhat unusual arrangement but one used at

least as early as the 6th century.^ Much more exceptional is the fact that she stands within

the precinct, rightly understood by Ratkowska to be the basilica at Nazareth, rather than

outside her house or seated within it, the more usual setting for the Annunciation. Follow-

ing Millet, however, the Polish scholar saw this feature as the expression of an 'Asiatic

milieu', a designation which would have to include the 10th-century wall paintings of St.

^ This problem is taken up by Anthony CUTLER, 'Visual Memory, Conceptual Models and the Question of "Artistic

Freedom"', [in:] L'artETa a ß&mzio e ne/ mon<7o cr/xfmno-or/enm/e, ed. M. Bacci, Pisa 2007, pp. 31-53.

^ RATKOWSKA, 'An East Christian Diptych', 107, calls it a 'colonnade'.

^ It occurs, e. g., on the Cathedra of Maximian, and the St.-Lupicin and Ejmiacin diptychs; W. F. VOLBACH, E//en&-

iTmrAe/ten &r Spd'mmAe mi<7 <7e,s/rń/ien Mńfe/a/fen, 3rd ed., Mainz 1976, nos. 140, 142, 145.

77. D/p7ycA wz'/A YCC/76A qA/Ac /i/e q/CArAf

(57. Pu/er.sAH/g, 5fa/c 7Vcrw//<rgc A7M,scMw)

The urge to explain visual phenomena in atavistic terms can mislead; moreover, it ig-

nores the likelihood that craftsmen enjoyed a good deal of liberty in the way that they

represented a canonical or commissioned theme.^ In particular, in their treatment of de-

tails such as those considered immediately above artists were free to deviate from what we

consider to be norms and, short of committing heresy, to introduce variations that in our

taxonomies and our eyes (but not necessarily their own or those of their clients) read as

innovations. One example would be the arcade in the Annunciation at Warsaw (ill. 5),^

already noted as a part of the diptych that has been damaged. Here Mary is approached

from the right by the archangel, itself a somewhat unusual arrangement but one used at

least as early as the 6th century.^ Much more exceptional is the fact that she stands within

the precinct, rightly understood by Ratkowska to be the basilica at Nazareth, rather than

outside her house or seated within it, the more usual setting for the Annunciation. Follow-

ing Millet, however, the Polish scholar saw this feature as the expression of an 'Asiatic

milieu', a designation which would have to include the 10th-century wall paintings of St.

^ This problem is taken up by Anthony CUTLER, 'Visual Memory, Conceptual Models and the Question of "Artistic

Freedom"', [in:] L'artETa a ß&mzio e ne/ mon<7o cr/xfmno-or/enm/e, ed. M. Bacci, Pisa 2007, pp. 31-53.

^ RATKOWSKA, 'An East Christian Diptych', 107, calls it a 'colonnade'.

^ It occurs, e. g., on the Cathedra of Maximian, and the St.-Lupicin and Ejmiacin diptychs; W. F. VOLBACH, E//en&-

iTmrAe/ten &r Spd'mmAe mi<7 <7e,s/rń/ien Mńfe/a/fen, 3rd ed., Mainz 1976, nos. 140, 142, 145.