194

PUNCH, OR THE LONDON CHAiUVAPL [Apbil 29, 1882,

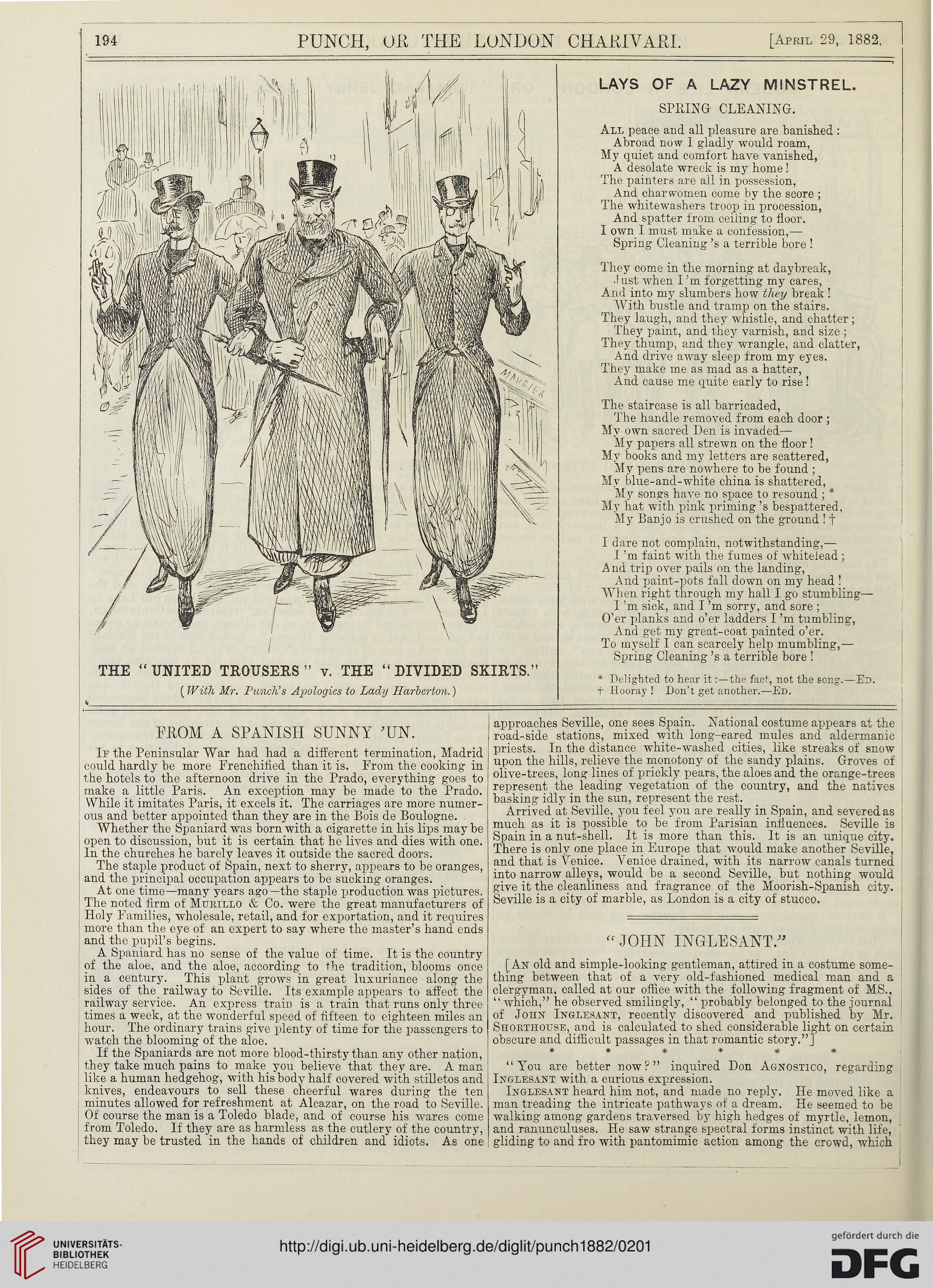

THE “UNITED TROUSERS ” v. THE “ DIVIDED SKIRTS.

(With Mr. Punch’s Apologies to Lccdy Harberton.)

LAYS OF A LAZY MINSTREL.

SPKING- CLEANINGr.

All peaee and all pleasure are banished :

Abroad now I gladl y would roam,

My quiet and comfort bave vanisbed,

A desolate wreek is my bome !

The painters are all in possession,

And charwomen come by tbe score ;

The whitewashers troop in procession,

And spatter from ceiling to fioor.

I own I must make a confession,—

Spring Cleaning ’s a terrible bore !

They come in the morning at daybreak,

.! ust when I !m forgetting my cares,

And into my slumbers how they break!

With bustle and tramp on the stairs.

They laugh, and they whistle, and chatter;

They paint, and they varnish, and size ;

They thump, and they wrangle, and clatter,

And drive away sleep from my eyes.

They make me as mad as a hatter,

And cause me quite early to rise !

The staircase is all barricaded,

The handle removed from each door ;

Mv own sacred Den is invaded—

My papers all strewn on the floor!

My books and my letters are scattered,

My pens are nowhere to be found ;

My blue-and-white china is shattered,

My songs have no space to resound ; *

My hat with pink priming ’s bespattered,

My Banjo is crushed on the ground ! t

I dare not complain, notwithstanding,—

I ’m faint with the f umes of whitefead ;

And trip over pails on the landing,

And paint-pots fall down on my head !

When right through my hall I go stumbling—

I ’m sick, and I ’m sorry, and sore ;

O’er planks and o’er ladders I ’m tumbling,

And get my great-coat painted o’er.

To tnyself I can scarcely help mumbling,—

Spring Cleaning ’s a terrible bore !

* Delighted to hear itthe fact, not the song.—En.

t Hooray ! Don’t get anotker.—Ed.

TBOM A SPANISIi SUNNY ’UN.

If the Peninsular War had had a different termination, Madrid

could hardly be more Frenchified than it is. From the cooking in

the hotels to the afternoon drive in the Prado, everything goes to

make a little Paris. An exception may be made to the Prado.

While it imitates Paris, it excels it. The carriages are more numer-

ous and better appointed than they are in the Bois de Boulogne.

Whether the Spaniard was born with a cigarette in his lips may be

open to discussion, but it is certain that he lives and dies with one.

In the churches he barely leaves it outside the sacred doors.

The staple product of Spain, next to sherry, appears to be oranges,

and the principal occupation appears to be sucking oranges.

At one time—many years ago—-the staple production was pictures.

The noted firm of' Murillo & Co. were the great manufacturers of

Holy Families, wholesale, retail, and for exportation, and it requires

more than the eye of an expert to say where the master’s hand ends

and the pupil’s begins.

A Spaniard has no sense of the value of time. It is the country

of the aloe, and the aloe, according to the tradition, blooms once

in a century. This plaut grows in great luxuriance along the

sides of the_ railway to Sevilie. Its example appears to affect the

railway service. An express traiD is a train that runs only three

times a week, at the wonderful speed of fifteen to eighteen miles an

hour. The ordinary trains give plenty of time for the passengers to

watch the blooming of the aloe.

If the Spaniards are not more blood-thirsty than any other nation,

they take much pains to make you believe that they are. A man

like a human hedgehog, with his body half covered with stilletos and

knives, endeavours to sell these cheerful wares during the ten

minutes allowed for refreshment at Alcazar, on the road to Seville.

Of course the man is a Toledo blade, and of course his wares come

from Toledo. If they are as harmless as the cutlery of the country,

they may be trusted in the hands of children and idiots. As one

approaches Seville, one sees Spain. National costume appears at the i

road-side stations, mixed with long-eared mules and aldermanic

priests. In the distance white-washed cities, like streaks of snow

upon the hills, relieve the monotony of the sandy plains. Groves of

olive-trees, long lines of prickly pears, the aloes and the orange-trees

represent the leading vegetation of the country, and the natives

basking idly in the sun, represent the rest.

Arrived at Seville, you feel you are really in Spain, and severedas

much as it is possible to be from Parisian influences. Seville is

Spain in a nut-shell. It is more than this. It is an unique city.

There is only one place in Europe that would make another Seville,

and that is Yenice. ’Venice drained, with its narrow eanals turned

into narrow alleys, would be a second Seville, but nothing would

give it the cleanliness and fragrance of the Moorish-Spanish city.

Seville is a city of marble, as London is a city of stucco.

“ JOHN INGLESANT.”

[An old and simple-looking gentleman, attired in a costume some-

thing between that of a very old-fashioned medical man and a

clergyman, called at our office with the following fragment of MS.,

“ which,” he observed smiliagly, “ probably beionged to the journal

of John Inglesant, recently discovered and published 'by Mr.

Shorthouse, and is calculated to shed considerable light on certain

obscure and difficult passages in that romantic story.”]

******

“ You are better now?” inquired Don Agnostico, regarding

Inglesant with a curious expression.

Inglesant heard him not, and made no reply. He moved like a

man treading the intricate pathways of' a dream. He seemed to be

walking among gardens traversed by high hedges of myrtle, lemon,

and ranunculuses. He saw strange spectral forms instinct with life,

gliding to and fro with pantomimic action among the crowd, whieh

i

PUNCH, OR THE LONDON CHAiUVAPL [Apbil 29, 1882,

THE “UNITED TROUSERS ” v. THE “ DIVIDED SKIRTS.

(With Mr. Punch’s Apologies to Lccdy Harberton.)

LAYS OF A LAZY MINSTREL.

SPKING- CLEANINGr.

All peaee and all pleasure are banished :

Abroad now I gladl y would roam,

My quiet and comfort bave vanisbed,

A desolate wreek is my bome !

The painters are all in possession,

And charwomen come by tbe score ;

The whitewashers troop in procession,

And spatter from ceiling to fioor.

I own I must make a confession,—

Spring Cleaning ’s a terrible bore !

They come in the morning at daybreak,

.! ust when I !m forgetting my cares,

And into my slumbers how they break!

With bustle and tramp on the stairs.

They laugh, and they whistle, and chatter;

They paint, and they varnish, and size ;

They thump, and they wrangle, and clatter,

And drive away sleep from my eyes.

They make me as mad as a hatter,

And cause me quite early to rise !

The staircase is all barricaded,

The handle removed from each door ;

Mv own sacred Den is invaded—

My papers all strewn on the floor!

My books and my letters are scattered,

My pens are nowhere to be found ;

My blue-and-white china is shattered,

My songs have no space to resound ; *

My hat with pink priming ’s bespattered,

My Banjo is crushed on the ground ! t

I dare not complain, notwithstanding,—

I ’m faint with the f umes of whitefead ;

And trip over pails on the landing,

And paint-pots fall down on my head !

When right through my hall I go stumbling—

I ’m sick, and I ’m sorry, and sore ;

O’er planks and o’er ladders I ’m tumbling,

And get my great-coat painted o’er.

To tnyself I can scarcely help mumbling,—

Spring Cleaning ’s a terrible bore !

* Delighted to hear itthe fact, not the song.—En.

t Hooray ! Don’t get anotker.—Ed.

TBOM A SPANISIi SUNNY ’UN.

If the Peninsular War had had a different termination, Madrid

could hardly be more Frenchified than it is. From the cooking in

the hotels to the afternoon drive in the Prado, everything goes to

make a little Paris. An exception may be made to the Prado.

While it imitates Paris, it excels it. The carriages are more numer-

ous and better appointed than they are in the Bois de Boulogne.

Whether the Spaniard was born with a cigarette in his lips may be

open to discussion, but it is certain that he lives and dies with one.

In the churches he barely leaves it outside the sacred doors.

The staple product of Spain, next to sherry, appears to be oranges,

and the principal occupation appears to be sucking oranges.

At one time—many years ago—-the staple production was pictures.

The noted firm of' Murillo & Co. were the great manufacturers of

Holy Families, wholesale, retail, and for exportation, and it requires

more than the eye of an expert to say where the master’s hand ends

and the pupil’s begins.

A Spaniard has no sense of the value of time. It is the country

of the aloe, and the aloe, according to the tradition, blooms once

in a century. This plaut grows in great luxuriance along the

sides of the_ railway to Sevilie. Its example appears to affect the

railway service. An express traiD is a train that runs only three

times a week, at the wonderful speed of fifteen to eighteen miles an

hour. The ordinary trains give plenty of time for the passengers to

watch the blooming of the aloe.

If the Spaniards are not more blood-thirsty than any other nation,

they take much pains to make you believe that they are. A man

like a human hedgehog, with his body half covered with stilletos and

knives, endeavours to sell these cheerful wares during the ten

minutes allowed for refreshment at Alcazar, on the road to Seville.

Of course the man is a Toledo blade, and of course his wares come

from Toledo. If they are as harmless as the cutlery of the country,

they may be trusted in the hands of children and idiots. As one

approaches Seville, one sees Spain. National costume appears at the i

road-side stations, mixed with long-eared mules and aldermanic

priests. In the distance white-washed cities, like streaks of snow

upon the hills, relieve the monotony of the sandy plains. Groves of

olive-trees, long lines of prickly pears, the aloes and the orange-trees

represent the leading vegetation of the country, and the natives

basking idly in the sun, represent the rest.

Arrived at Seville, you feel you are really in Spain, and severedas

much as it is possible to be from Parisian influences. Seville is

Spain in a nut-shell. It is more than this. It is an unique city.

There is only one place in Europe that would make another Seville,

and that is Yenice. ’Venice drained, with its narrow eanals turned

into narrow alleys, would be a second Seville, but nothing would

give it the cleanliness and fragrance of the Moorish-Spanish city.

Seville is a city of marble, as London is a city of stucco.

“ JOHN INGLESANT.”

[An old and simple-looking gentleman, attired in a costume some-

thing between that of a very old-fashioned medical man and a

clergyman, called at our office with the following fragment of MS.,

“ which,” he observed smiliagly, “ probably beionged to the journal

of John Inglesant, recently discovered and published 'by Mr.

Shorthouse, and is calculated to shed considerable light on certain

obscure and difficult passages in that romantic story.”]

******

“ You are better now?” inquired Don Agnostico, regarding

Inglesant with a curious expression.

Inglesant heard him not, and made no reply. He moved like a

man treading the intricate pathways of' a dream. He seemed to be

walking among gardens traversed by high hedges of myrtle, lemon,

and ranunculuses. He saw strange spectral forms instinct with life,

gliding to and fro with pantomimic action among the crowd, whieh

i