Japanese Chasing and Chasers

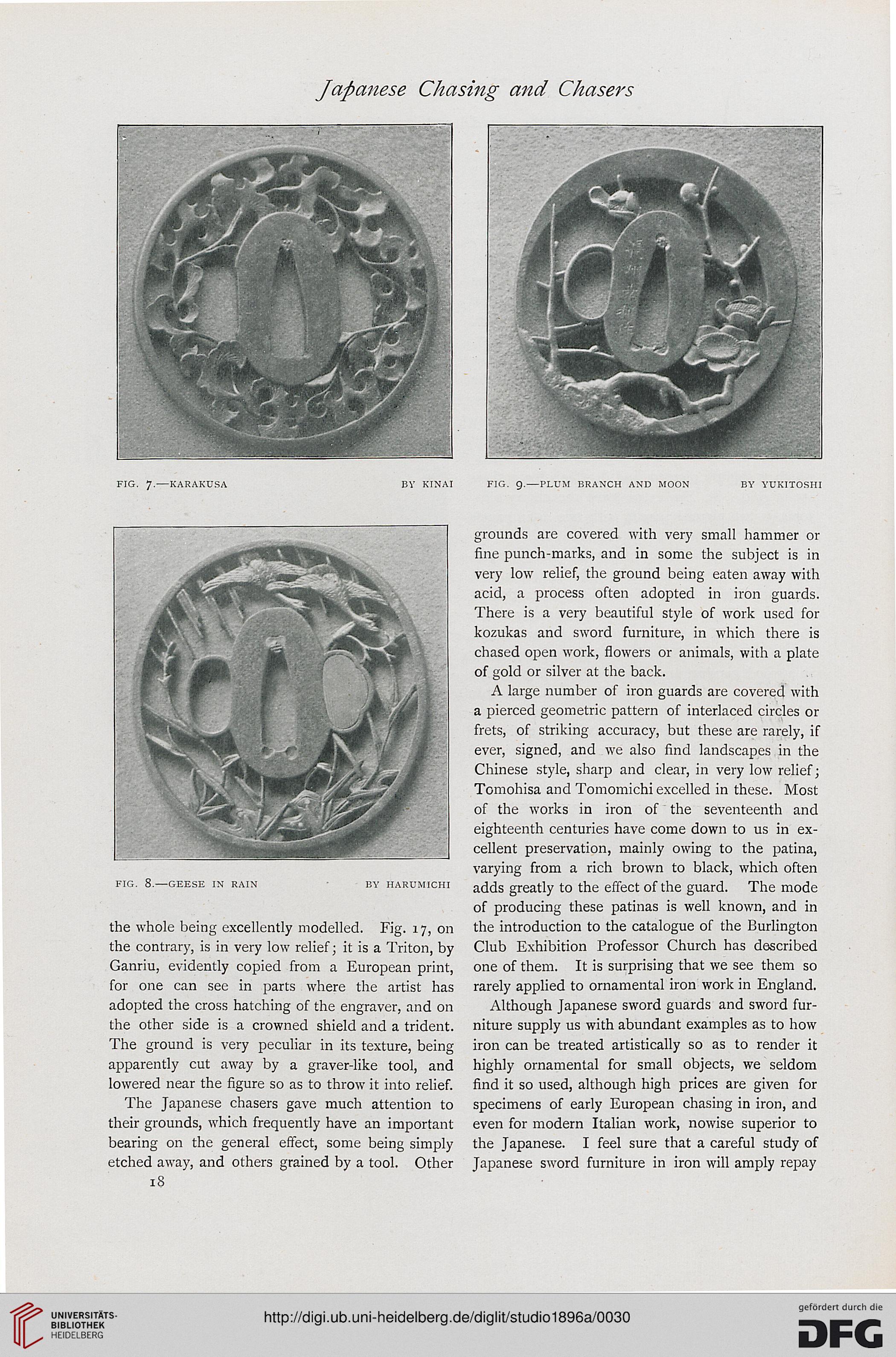

FIG. 8.—GEESE IN RAIN BY HARUMICHI

the whole being excellently modelled. Fig. 17, on

the contrary, is in very low relief; it is a Triton, by

Ganriu, evidently copied from a European print,

for one can see in parts where the artist has

adopted the cross hatching of the engraver, and on

the other side is a crowned shield and a trident.

The ground is very peculiar in its texture, being

apparently cut away by a graver-like tool, and

lowered near the figure so as to throw it into relief.

The Japanese chasers gave much attention to

their grounds, which frequently have an important

bearing on the general effect, some being simply

etched away, and others grained by a tool. Other

18

FIG. 9.—PLUM BRANCH AND MOON BY YUKITOSIII

grounds are covered with very small hammer or

fine punch-marks, and in some the subject is in

very low relief, the ground being eaten away with

acid, a process often adopted in iron guards.

There is a very beautiful style of work used for

kozukas and sword furniture, in which there is

chased open work, flowers or animals, with a plate

of gold or silver at the back.

A large number of iron guards are covered with

a pierced geometric pattern of interlaced circles or

frets, of striking accuracy, but these are rarely, if

ever, signed, and we also find landscapes in the

Chinese style, sharp and clear, in very low relief;

Tomohisa and Tomomichi excelled in these. Most

of the works in iron of the seventeenth and

eighteenth centuries have come down to us in ex-

cellent preservation, mainly owing to the patina,

varying from a rich brown to black, which often

adds greatly to the effect of the guard. The mode

of producing these patinas is well known, and in

the introduction to the catalogue of the Burlington

Club Exhibition Professor Church has described

one of them. It is surprising that we see them so

rarely applied to ornamental iron work in England.

Although Japanese sword guards and sword fur-

niture supply us with abundant examples as to how

iron can be treated artistically so as to render it

highly ornamental for small objects, we seldom

find it so used, although high prices are given for

specimens of early European chasing in iron, and

even for modern Italian work, nowise superior to

the Japanese. I feel sure that a careful study of

Japanese sword furniture in iron will amply repay

FIG. 8.—GEESE IN RAIN BY HARUMICHI

the whole being excellently modelled. Fig. 17, on

the contrary, is in very low relief; it is a Triton, by

Ganriu, evidently copied from a European print,

for one can see in parts where the artist has

adopted the cross hatching of the engraver, and on

the other side is a crowned shield and a trident.

The ground is very peculiar in its texture, being

apparently cut away by a graver-like tool, and

lowered near the figure so as to throw it into relief.

The Japanese chasers gave much attention to

their grounds, which frequently have an important

bearing on the general effect, some being simply

etched away, and others grained by a tool. Other

18

FIG. 9.—PLUM BRANCH AND MOON BY YUKITOSIII

grounds are covered with very small hammer or

fine punch-marks, and in some the subject is in

very low relief, the ground being eaten away with

acid, a process often adopted in iron guards.

There is a very beautiful style of work used for

kozukas and sword furniture, in which there is

chased open work, flowers or animals, with a plate

of gold or silver at the back.

A large number of iron guards are covered with

a pierced geometric pattern of interlaced circles or

frets, of striking accuracy, but these are rarely, if

ever, signed, and we also find landscapes in the

Chinese style, sharp and clear, in very low relief;

Tomohisa and Tomomichi excelled in these. Most

of the works in iron of the seventeenth and

eighteenth centuries have come down to us in ex-

cellent preservation, mainly owing to the patina,

varying from a rich brown to black, which often

adds greatly to the effect of the guard. The mode

of producing these patinas is well known, and in

the introduction to the catalogue of the Burlington

Club Exhibition Professor Church has described

one of them. It is surprising that we see them so

rarely applied to ornamental iron work in England.

Although Japanese sword guards and sword fur-

niture supply us with abundant examples as to how

iron can be treated artistically so as to render it

highly ornamental for small objects, we seldom

find it so used, although high prices are given for

specimens of early European chasing in iron, and

even for modern Italian work, nowise superior to

the Japanese. I feel sure that a careful study of

Japanese sword furniture in iron will amply repay