Ceramic Art of the Pueblo Indians

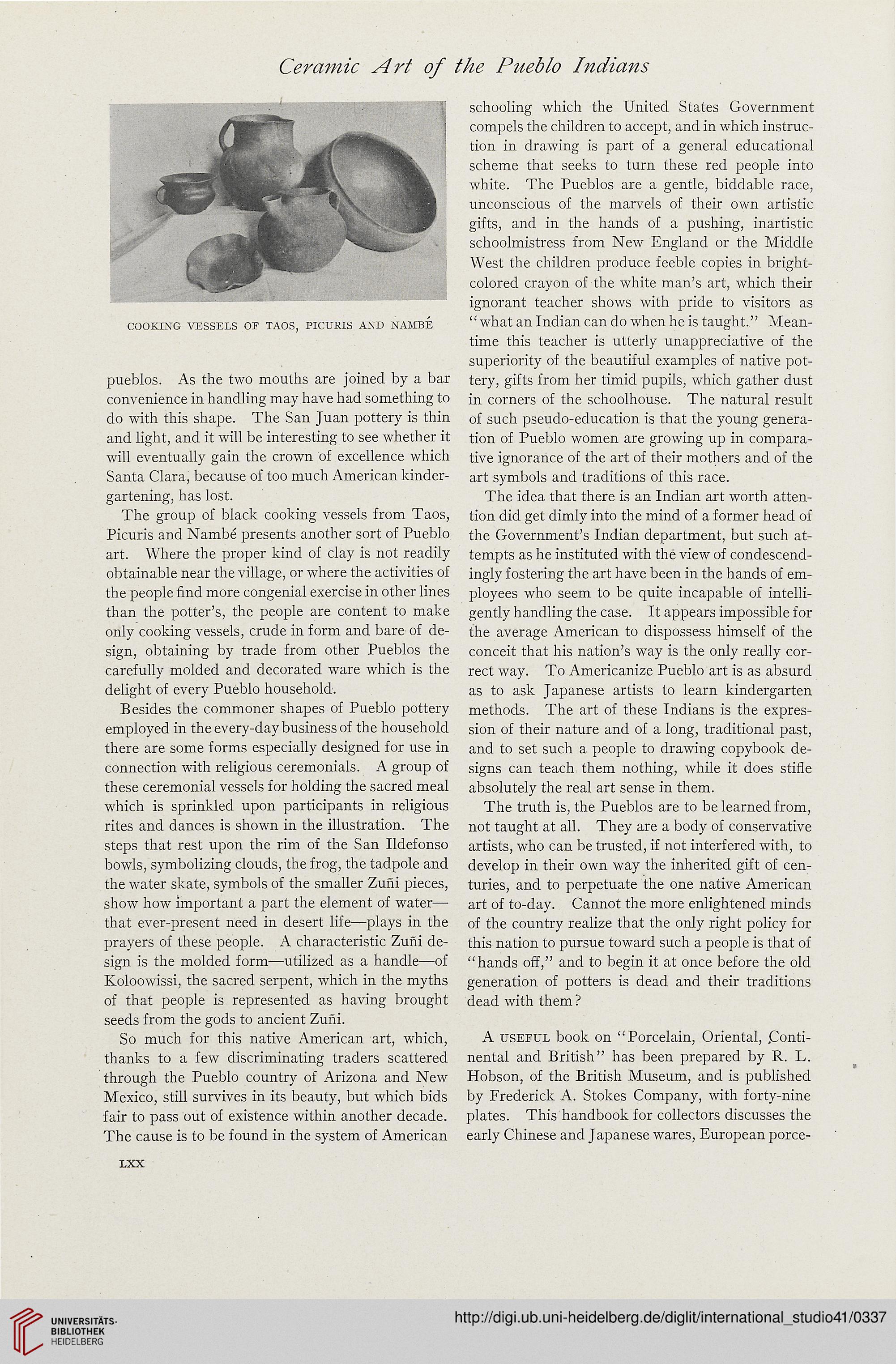

cooking vessels of taos, picuris and nambe

pueblos. As the two mouths are joined by a bar

convenience in handling may have had something to

do with this shape. The San Juan pottery is thin

and light, and it will be interesting to see whether it

will eventually gain the crown of excellence which

Santa Clara, because of too much American kinder-

gartening, has lost.

The group of black cooking vessels from Taos,

Picuris and Nambe presents another sort of Pueblo

art. Where the proper kind of clay is not readily

obtainable near the village, or where the activities of

the people find more congenial exercise in other lines

than the potter's, the people are content to make

only cooking vessels, crude in form and bare of de-

sign, obtaining by trade from other Pueblos the

carefully molded and decorated ware which is the

delight of every Pueblo household.

Besides the commoner shapes of Pueblo pottery

employed in the every-day business of the household

there are some forms especially designed for use in

connection with religious ceremonials. A group of

these ceremonial vessels for holding the sacred meal

which is sprinkled upon participants in religious

rites and dances is shown in the illustration. The

steps that rest upon the rim of the San Ildefonso

bowls, symbolizing clouds, the frog, the tadpole and

the water skate, symbols of the smaller Zufii pieces,

show how important a part the element of water—

that ever-present need in desert life—plays in the

prayers of these people. A characteristic Zufii de-

sign is the molded form—utilized as a handle—of

Koloowissi, the sacred serpent, which in the myths

of that people is represented as having brought

seeds from the gods to ancient Zufii.

So much for this native American art, which,

thanks to a few discriminating traders scattered

through the Pueblo country of Arizona and New

Mexico, still survives in its beauty, but which bids

fair to pass out of existence within another decade.

The cause is to be found in the system of American

lxx

schooling which the United States Government

compels the children to accept, and in which instruc-

tion in drawing is part of a general educational

scheme that seeks to turn these red people into

white. The Pueblos are a gentle, biddable race,

unconscious of the marvels of their own artistic

gifts, and in the hands of a pushing, inartistic

schoolmistress from New England or the Middle

West the children produce feeble copies in bright-

colored crayon of the white man's art, which their

ignorant teacher shows with pride to visitors as

"what an Indian can do when he is taught." Mean-

time this teacher is utterly unappreciative of the

superiority of the beautiful examples of native pot-

tery, gifts from her timid pupils, which gather dust

in corners of the schoolhouse. The natural result

of such pseudo-education is that the young genera-

tion of Pueblo women are growing up in compara-

tive ignorance of the art of their mothers and of the

art symbols and traditions of this race.

The idea that there is an Indian art worth atten-

tion did get dimly into the mind of a former head of

the Government's Indian department, but such at-

tempts as he instituted with the view of condescend-

ingly fostering the art have been in the hands of em-

ployees who seem to be quite incapable of intelli-

gently handling the case. It appears impossible for

the average American to dispossess himself of the

conceit that his nation's way is the only really cor-

rect way. To Americanize Pueblo art is as absurd

as to ask Japanese artists to learn kindergarten

methods. The art of these Indians is the expres-

sion of their nature and of a long, traditional past,

and to set such a people to drawing copybook de-

signs can teach them nothing, while it does stifle

absolutely the real art sense in them.

The truth is, the Pueblos are to be learned from,

not taught at all. They are a body of conservative

artists, who can be trusted, if not interfered with, to

develop in their own way the inherited gift of cen-

turies, and to perpetuate the one native American

art of to-day. Cannot the more enlightened minds

of the country realize that the only right policy for

this nation to pursue toward such a people is that of

"hands off," and to begin it at once before the old

generation of potters is dead and their traditions

dead with them ?

A useful book on "Porcelain, Oriental, Conti-

nental and British" has been prepared by R. L.

Hobson, of the British Museum, and is published

by Frederick A. Stokes Company, with forty-nine

plates. This handbook for collectors discusses the

early Chinese and Japanese wares, European porce-

cooking vessels of taos, picuris and nambe

pueblos. As the two mouths are joined by a bar

convenience in handling may have had something to

do with this shape. The San Juan pottery is thin

and light, and it will be interesting to see whether it

will eventually gain the crown of excellence which

Santa Clara, because of too much American kinder-

gartening, has lost.

The group of black cooking vessels from Taos,

Picuris and Nambe presents another sort of Pueblo

art. Where the proper kind of clay is not readily

obtainable near the village, or where the activities of

the people find more congenial exercise in other lines

than the potter's, the people are content to make

only cooking vessels, crude in form and bare of de-

sign, obtaining by trade from other Pueblos the

carefully molded and decorated ware which is the

delight of every Pueblo household.

Besides the commoner shapes of Pueblo pottery

employed in the every-day business of the household

there are some forms especially designed for use in

connection with religious ceremonials. A group of

these ceremonial vessels for holding the sacred meal

which is sprinkled upon participants in religious

rites and dances is shown in the illustration. The

steps that rest upon the rim of the San Ildefonso

bowls, symbolizing clouds, the frog, the tadpole and

the water skate, symbols of the smaller Zufii pieces,

show how important a part the element of water—

that ever-present need in desert life—plays in the

prayers of these people. A characteristic Zufii de-

sign is the molded form—utilized as a handle—of

Koloowissi, the sacred serpent, which in the myths

of that people is represented as having brought

seeds from the gods to ancient Zufii.

So much for this native American art, which,

thanks to a few discriminating traders scattered

through the Pueblo country of Arizona and New

Mexico, still survives in its beauty, but which bids

fair to pass out of existence within another decade.

The cause is to be found in the system of American

lxx

schooling which the United States Government

compels the children to accept, and in which instruc-

tion in drawing is part of a general educational

scheme that seeks to turn these red people into

white. The Pueblos are a gentle, biddable race,

unconscious of the marvels of their own artistic

gifts, and in the hands of a pushing, inartistic

schoolmistress from New England or the Middle

West the children produce feeble copies in bright-

colored crayon of the white man's art, which their

ignorant teacher shows with pride to visitors as

"what an Indian can do when he is taught." Mean-

time this teacher is utterly unappreciative of the

superiority of the beautiful examples of native pot-

tery, gifts from her timid pupils, which gather dust

in corners of the schoolhouse. The natural result

of such pseudo-education is that the young genera-

tion of Pueblo women are growing up in compara-

tive ignorance of the art of their mothers and of the

art symbols and traditions of this race.

The idea that there is an Indian art worth atten-

tion did get dimly into the mind of a former head of

the Government's Indian department, but such at-

tempts as he instituted with the view of condescend-

ingly fostering the art have been in the hands of em-

ployees who seem to be quite incapable of intelli-

gently handling the case. It appears impossible for

the average American to dispossess himself of the

conceit that his nation's way is the only really cor-

rect way. To Americanize Pueblo art is as absurd

as to ask Japanese artists to learn kindergarten

methods. The art of these Indians is the expres-

sion of their nature and of a long, traditional past,

and to set such a people to drawing copybook de-

signs can teach them nothing, while it does stifle

absolutely the real art sense in them.

The truth is, the Pueblos are to be learned from,

not taught at all. They are a body of conservative

artists, who can be trusted, if not interfered with, to

develop in their own way the inherited gift of cen-

turies, and to perpetuate the one native American

art of to-day. Cannot the more enlightened minds

of the country realize that the only right policy for

this nation to pursue toward such a people is that of

"hands off," and to begin it at once before the old

generation of potters is dead and their traditions

dead with them ?

A useful book on "Porcelain, Oriental, Conti-

nental and British" has been prepared by R. L.

Hobson, of the British Museum, and is published

by Frederick A. Stokes Company, with forty-nine

plates. This handbook for collectors discusses the

early Chinese and Japanese wares, European porce-