universitats*

bibliothek

HEIDELBERG

s"J

/. Francis Murphy

appreciation to-day is represented, on the one hand

by a kind of fraternity of aesthetic Rip Van Win-

kles, to whom Inness, Wyant or Martin represent

the last word in American painting, and on the

other by a horde of irresponsibles who, in Wilde’s

felicitous phrase, can believe anything, so long as

it is incredible, but who can never, by any means,

comprehend the difficult nobility, the heroism (for

such it has indeed become) of standing guard over

tradition and reserve at a time when the fashions

of the hour mock sobriety, sentiment and morale.

Midway between these two injurious extremes you

find Murphy, a man of a keen, nimble, nervous

mentality, an inestimable combination of the old

and the new, a progressive, an explorer with the

best of them, but only—mark the distinction—in

so far as he can reconcile development with what

his conscience assures him is truth and beauty.

In the Leslie Ward sale some three years ago a

picture by Murphy sold for $2,600. At that time

Murphy’s price for that particular sized picture

was $650. When his Hillside Farm brought

$4,000 in the Evans sale it brought a trifle over

four times the price Mr. Evans had paid for it.

The two instances, chosen from a dozen such, sup-

ply emphatic examples of a living American paint-

er’s auction-room record that is both legitimately

significant and in many ways unique. It is the

inevitable reflex of that fortunate combination of

circumstances which has brought Murphy his

present large measure of conspicuousness. His

spurs have been won openly and honestly on his

merits as a conscientious builder for the future, on

his reputation as a man of an almost eccentric

aloofness from the ruts and pitfalls of patronage

and commercialism. The nervous tension result-

ing from the tenaciousness with which he grips his

artistic ideals might lead a superficial judgment to

censure him for an intolerance, an irascibility, a

kind of flurried impatience of restraint. He has

mostly isolated himself from the meretricious ad-

vices about him, and pursuing a preconceived

campaign, constituted himself a tyrannical sentry

over injudicious and shortsighted suggestion. He

is content with a comparatively scanty output of

ten or a dozen pictures a year. “I have had few

wants,” he says, “and therefore I’ve been doubly

able to remain my own master.” A kind of genial

asceticism rather fated to be misunderstood in so

industrious, so mercenary a generation. Hasty

and ill-considered workmanship is eliminated from

his scheme of things, and nothing will contribute

so definitely to a future’s high appraisal of his

work as the respect he has shown for his artistic

integrity.

No approach to a just estimate of his possible

value can be reached by any one unsympathetic to

the frugal simplicity, the native sweetness of his

point of view. Clean as a nut, blithe, boyish and

spirited, it remains essentially youthful and essen-

tially proud of its American birthright. Winslow

Homer, for all the bite and twang of his roaring,

epical blank verse, is not more saturated with a

national feeling, not more definitely removed from

the contaminating immigration of alien and arti-

ficial influences. True, Murphy has been called

the Corot of America (a kind of sombre Corot),

but the resemblance is largely superficial, residing

in some occasional similarity of treatment.

Murphy is closer to the root of things, his sym-

pathies dip deeper into a rank, pungent, solid,

substantial earth; he affectionately interprets the

arid reticence of naked and disabled

areas, of wasted, poverty-stricken

spaces and the loneliness of field and

farm. His is a kind of dry, plaintive

lyricism, with something of the wist-

ful quality of a folksong or music of

a sectional character, like Grieg or

Smetana. His two feet are planted

on a mere every-day, homely country-

side, fundamentally domestic, but the

result is always a transposition into

an idealized reality. Perhaps no one

painting to-day conveys so inevitable

an assurance of reality with so im-

maculate and delicate a loveliness of

method. “ I paint the woods I saw

as a boy,” Murphy says, momentarily

retrospective, and here, for better or

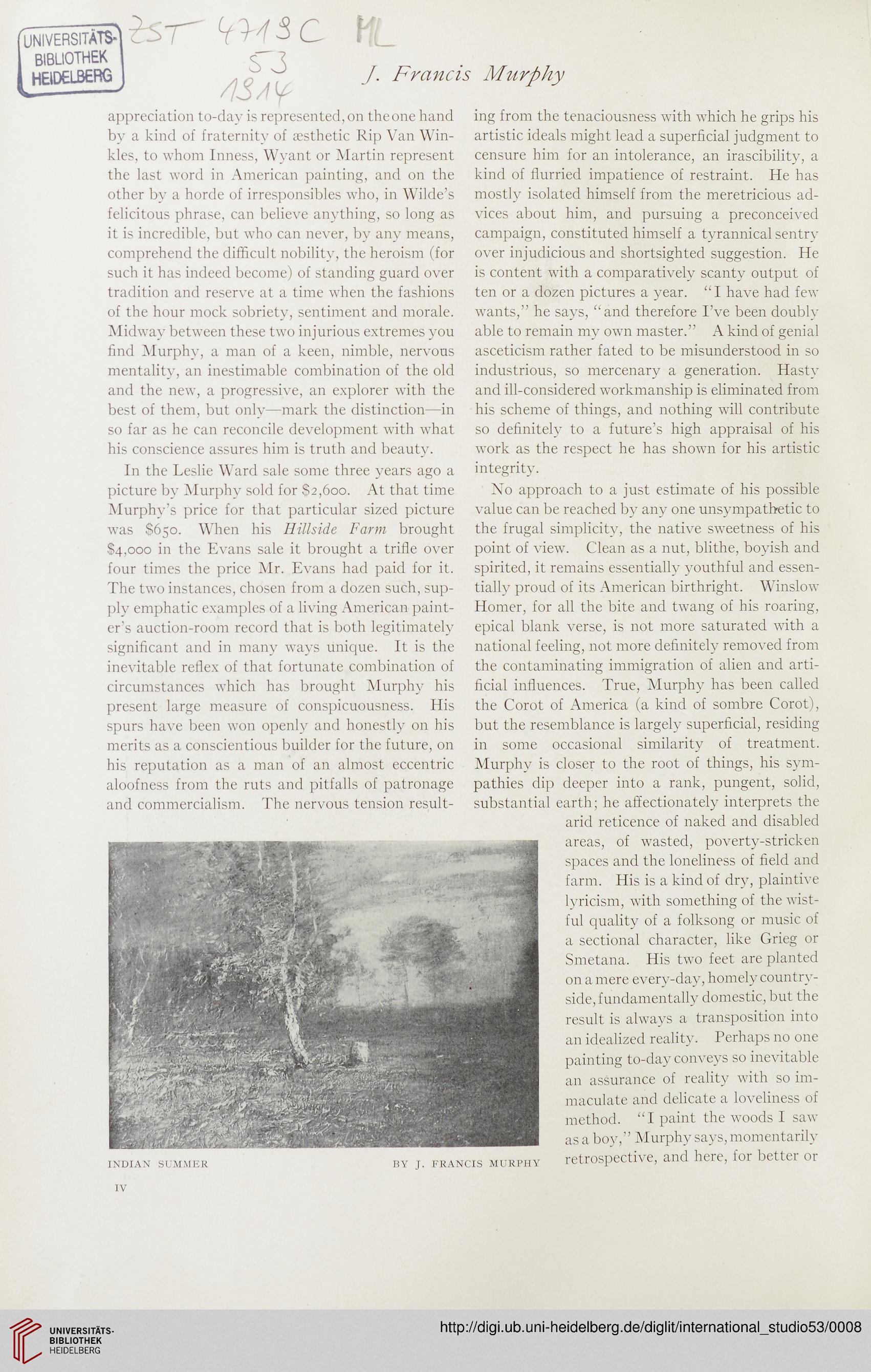

INDIAN SUMMER

BY J. FRANCIS MURPIIY

IV

bibliothek

HEIDELBERG

s"J

/. Francis Murphy

appreciation to-day is represented, on the one hand

by a kind of fraternity of aesthetic Rip Van Win-

kles, to whom Inness, Wyant or Martin represent

the last word in American painting, and on the

other by a horde of irresponsibles who, in Wilde’s

felicitous phrase, can believe anything, so long as

it is incredible, but who can never, by any means,

comprehend the difficult nobility, the heroism (for

such it has indeed become) of standing guard over

tradition and reserve at a time when the fashions

of the hour mock sobriety, sentiment and morale.

Midway between these two injurious extremes you

find Murphy, a man of a keen, nimble, nervous

mentality, an inestimable combination of the old

and the new, a progressive, an explorer with the

best of them, but only—mark the distinction—in

so far as he can reconcile development with what

his conscience assures him is truth and beauty.

In the Leslie Ward sale some three years ago a

picture by Murphy sold for $2,600. At that time

Murphy’s price for that particular sized picture

was $650. When his Hillside Farm brought

$4,000 in the Evans sale it brought a trifle over

four times the price Mr. Evans had paid for it.

The two instances, chosen from a dozen such, sup-

ply emphatic examples of a living American paint-

er’s auction-room record that is both legitimately

significant and in many ways unique. It is the

inevitable reflex of that fortunate combination of

circumstances which has brought Murphy his

present large measure of conspicuousness. His

spurs have been won openly and honestly on his

merits as a conscientious builder for the future, on

his reputation as a man of an almost eccentric

aloofness from the ruts and pitfalls of patronage

and commercialism. The nervous tension result-

ing from the tenaciousness with which he grips his

artistic ideals might lead a superficial judgment to

censure him for an intolerance, an irascibility, a

kind of flurried impatience of restraint. He has

mostly isolated himself from the meretricious ad-

vices about him, and pursuing a preconceived

campaign, constituted himself a tyrannical sentry

over injudicious and shortsighted suggestion. He

is content with a comparatively scanty output of

ten or a dozen pictures a year. “I have had few

wants,” he says, “and therefore I’ve been doubly

able to remain my own master.” A kind of genial

asceticism rather fated to be misunderstood in so

industrious, so mercenary a generation. Hasty

and ill-considered workmanship is eliminated from

his scheme of things, and nothing will contribute

so definitely to a future’s high appraisal of his

work as the respect he has shown for his artistic

integrity.

No approach to a just estimate of his possible

value can be reached by any one unsympathetic to

the frugal simplicity, the native sweetness of his

point of view. Clean as a nut, blithe, boyish and

spirited, it remains essentially youthful and essen-

tially proud of its American birthright. Winslow

Homer, for all the bite and twang of his roaring,

epical blank verse, is not more saturated with a

national feeling, not more definitely removed from

the contaminating immigration of alien and arti-

ficial influences. True, Murphy has been called

the Corot of America (a kind of sombre Corot),

but the resemblance is largely superficial, residing

in some occasional similarity of treatment.

Murphy is closer to the root of things, his sym-

pathies dip deeper into a rank, pungent, solid,

substantial earth; he affectionately interprets the

arid reticence of naked and disabled

areas, of wasted, poverty-stricken

spaces and the loneliness of field and

farm. His is a kind of dry, plaintive

lyricism, with something of the wist-

ful quality of a folksong or music of

a sectional character, like Grieg or

Smetana. His two feet are planted

on a mere every-day, homely country-

side, fundamentally domestic, but the

result is always a transposition into

an idealized reality. Perhaps no one

painting to-day conveys so inevitable

an assurance of reality with so im-

maculate and delicate a loveliness of

method. “ I paint the woods I saw

as a boy,” Murphy says, momentarily

retrospective, and here, for better or

INDIAN SUMMER

BY J. FRANCIS MURPIIY

IV