Modern Tendencies in Japanese Sculpture

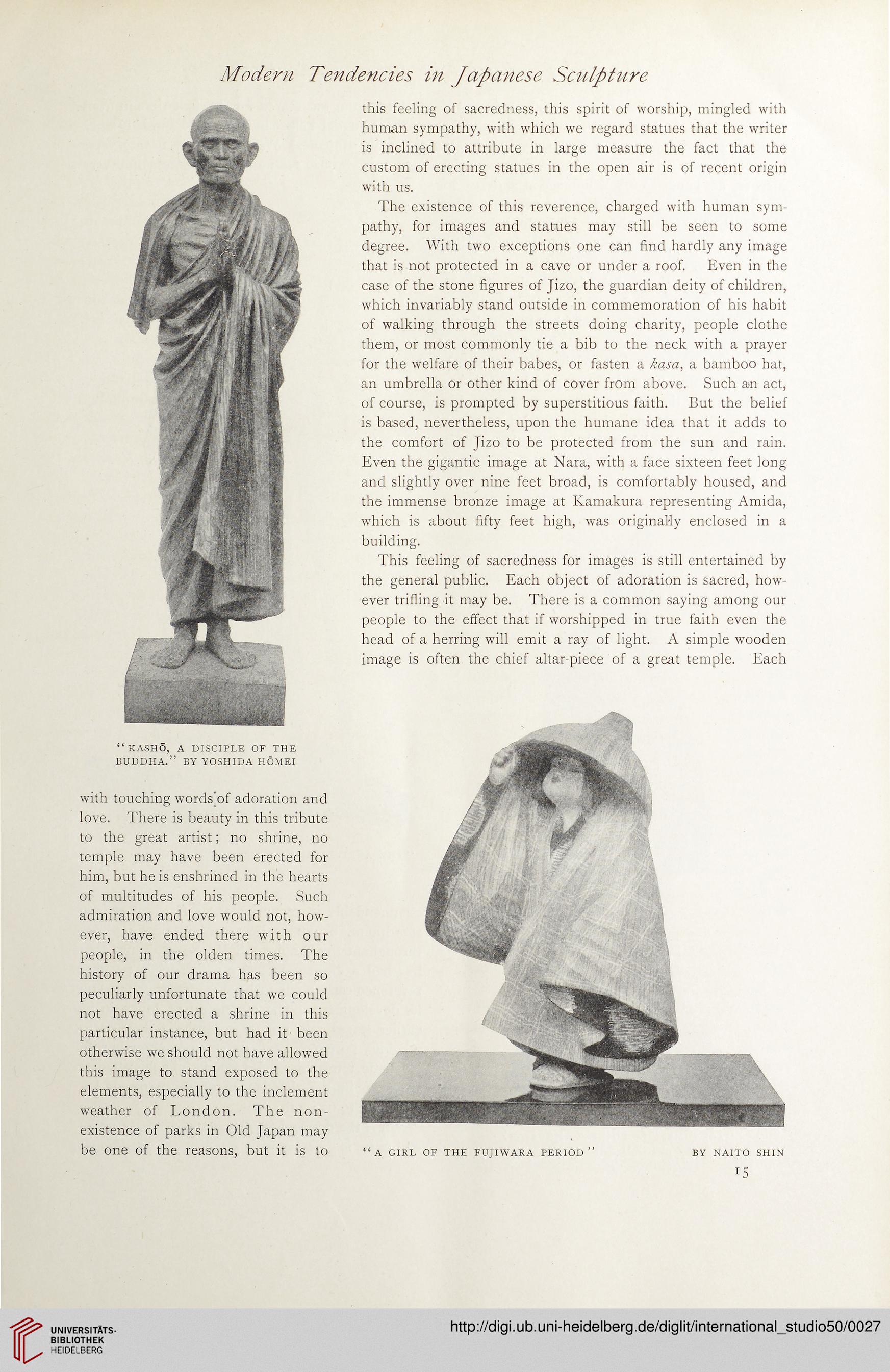

“ KASHO, A DISCIPLE OF THE

BUDDHA.” BY YOSHIDA HOMEI

with touching words'of adoration and

love. There is beauty in this tribute

to the great artist; no shrine, no

temple may have been erected for

him, but he is enshrined in the hearts

of multitudes of his people. Such

admiration and love would not, how-

ever, have ended there with our

people, in the olden times. The

history of our drama has been so

peculiarly unfortunate that we could

not have erected a shrine in this

particular instance, but had it been

otherwise we should not have allowed

this image to stand exposed to the

elements, especially to the inclement

weather of London. The non-

existence of parks in Old Japan may

be one of the reasons, but it is to

this feeling of sacredness, this spirit of worship, mingled with

human sympathy, with which we regard statues that the writer

is inclined to attribute in large measure the fact that the

custom of erecting statues in the open air is of recent origin

with us.

The existence of this reverence, charged with human sym-

pathy, for images and statues may still be seen to some

degree. With two exceptions one can find hardly any image

that is not protected in a cave or under a roof. Even in the

case of the stone figures of Jizo, the guardian deity of children,

which invariably stand outside in commemoration of his habit

of walking through the streets doing charity, people clothe

them, or most commonly tie a bib to the neck with a prayer

for the welfare of their babes, or fasten a kasa, a bamboo hat,

an umbrella or other kind of cover from above. Such an act,

of course, is prompted by superstitious faith. But the belief

is based, nevertheless, upon the humane idea that it adds to

the comfort of Jizo to be protected from the sun and rain.

Even the gigantic image at Nara, with a face sixteen feet long

and slightly over nine feet broad, is comfortably housed, and

the immense bronze image at Kamakura representing Amida,

which is about fifty feet high, was originally enclosed in a

building.

This feeling of sacredness for images is still entertained by

the general public. Each object of adoration is sacred, how-

ever trifling it may be. There is a common saying among our

people to the effect that if worshipped in true faith even the

head of a herring will emit a ray of light. A simple wooden

image is often the chief altar-piece of a great temple. Each

“ KASHO, A DISCIPLE OF THE

BUDDHA.” BY YOSHIDA HOMEI

with touching words'of adoration and

love. There is beauty in this tribute

to the great artist; no shrine, no

temple may have been erected for

him, but he is enshrined in the hearts

of multitudes of his people. Such

admiration and love would not, how-

ever, have ended there with our

people, in the olden times. The

history of our drama has been so

peculiarly unfortunate that we could

not have erected a shrine in this

particular instance, but had it been

otherwise we should not have allowed

this image to stand exposed to the

elements, especially to the inclement

weather of London. The non-

existence of parks in Old Japan may

be one of the reasons, but it is to

this feeling of sacredness, this spirit of worship, mingled with

human sympathy, with which we regard statues that the writer

is inclined to attribute in large measure the fact that the

custom of erecting statues in the open air is of recent origin

with us.

The existence of this reverence, charged with human sym-

pathy, for images and statues may still be seen to some

degree. With two exceptions one can find hardly any image

that is not protected in a cave or under a roof. Even in the

case of the stone figures of Jizo, the guardian deity of children,

which invariably stand outside in commemoration of his habit

of walking through the streets doing charity, people clothe

them, or most commonly tie a bib to the neck with a prayer

for the welfare of their babes, or fasten a kasa, a bamboo hat,

an umbrella or other kind of cover from above. Such an act,

of course, is prompted by superstitious faith. But the belief

is based, nevertheless, upon the humane idea that it adds to

the comfort of Jizo to be protected from the sun and rain.

Even the gigantic image at Nara, with a face sixteen feet long

and slightly over nine feet broad, is comfortably housed, and

the immense bronze image at Kamakura representing Amida,

which is about fifty feet high, was originally enclosed in a

building.

This feeling of sacredness for images is still entertained by

the general public. Each object of adoration is sacred, how-

ever trifling it may be. There is a common saying among our

people to the effect that if worshipped in true faith even the

head of a herring will emit a ray of light. A simple wooden

image is often the chief altar-piece of a great temple. Each