Orlando Rouland

mate needs, the purpose and end of art is expres-

sion.

A portrait at its best is the expression of per-

sonality. But the art of portraiture, like all other

art, is conditioned by certain limitations. There is,

first of all, the artist’s responsibility to his sitter;

his work is bound by obligations to the objective

fact. The portrait must be a likeness: otherwise,

it may be a figure study or an arrangement; it is

not truly a portrait. Then a portrait, as with all

painting, must be a pleasureable thing to look at;

it must fill a certain space agreeably; and by the

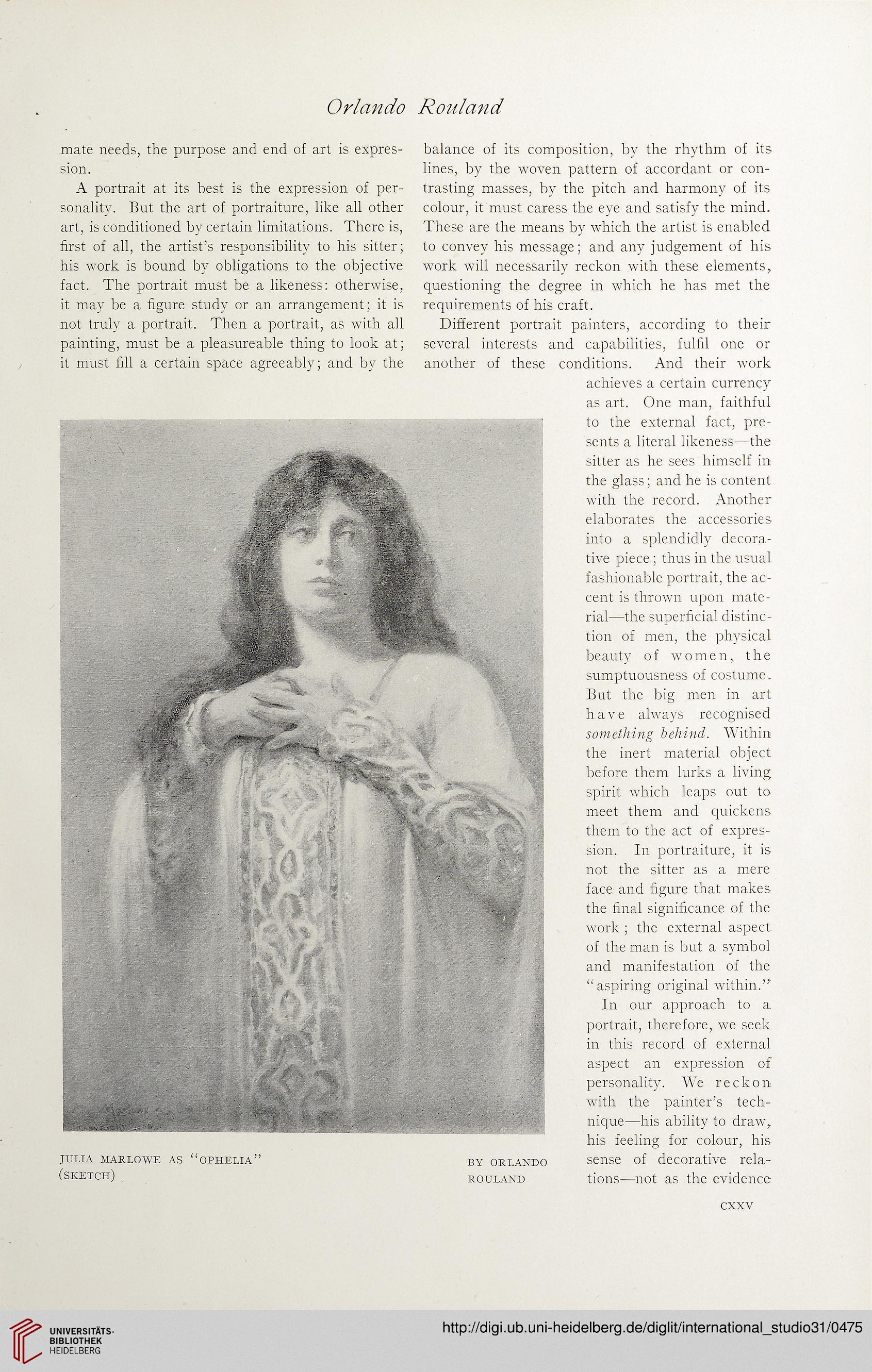

JULIA MARLOWE AS “OPHELIA”

(sketch)

balance of its composition, by the rhythm of its

lines, by the woven pattern of accordant or con-

trasting masses, by the pitch and harmony of its

colour, it must caress the eye and satisfy the mind.

These are the means by which the artist is enabled

to convey his message; and any judgement of his

work will necessarily reckon with these elements,

questioning the degree in which he has met the

requirements of his craft.

Different portrait painters, according to their

several interests and capabilities, fulfil one or

another of these conditions. And their work

achieves a certain currency

as art. One man, faithful

to the external fact, pre-

sents a literal likeness—the

sitter as he sees himself in

the glass; and he is content

with the record. Another

elaborates the accessories

into a splendidly decora-

tive piece ; thus in the usual

fashionable portrait, the ac-

cent is thrown upon mate-

rial—the superficial distinc-

tion of men, the physical

beauty of women, the

sumptuousness of costume.

But the big men in art

have always recognised

something behind. Within

the inert material object

before them lurks a living

spirit which leaps out to

meet them and quickens

them to the act of expres-

sion. In portraiture, it is

not the sitter as a mere

face and figure that makes

the final significance of the

work ; the external aspect

of the man is but a symbol

and manifestation of the

“aspiring original within.’r

In our approach to a

portrait, therefore, we seek

in this record of external

aspect an expression of

personality. We reckon

with the painter’s tech-

nique—his ability to draw,

his feeling for colour, his

by orlando sense of decorative rela-

rouland tions—not as the evidence

cxxv

mate needs, the purpose and end of art is expres-

sion.

A portrait at its best is the expression of per-

sonality. But the art of portraiture, like all other

art, is conditioned by certain limitations. There is,

first of all, the artist’s responsibility to his sitter;

his work is bound by obligations to the objective

fact. The portrait must be a likeness: otherwise,

it may be a figure study or an arrangement; it is

not truly a portrait. Then a portrait, as with all

painting, must be a pleasureable thing to look at;

it must fill a certain space agreeably; and by the

JULIA MARLOWE AS “OPHELIA”

(sketch)

balance of its composition, by the rhythm of its

lines, by the woven pattern of accordant or con-

trasting masses, by the pitch and harmony of its

colour, it must caress the eye and satisfy the mind.

These are the means by which the artist is enabled

to convey his message; and any judgement of his

work will necessarily reckon with these elements,

questioning the degree in which he has met the

requirements of his craft.

Different portrait painters, according to their

several interests and capabilities, fulfil one or

another of these conditions. And their work

achieves a certain currency

as art. One man, faithful

to the external fact, pre-

sents a literal likeness—the

sitter as he sees himself in

the glass; and he is content

with the record. Another

elaborates the accessories

into a splendidly decora-

tive piece ; thus in the usual

fashionable portrait, the ac-

cent is thrown upon mate-

rial—the superficial distinc-

tion of men, the physical

beauty of women, the

sumptuousness of costume.

But the big men in art

have always recognised

something behind. Within

the inert material object

before them lurks a living

spirit which leaps out to

meet them and quickens

them to the act of expres-

sion. In portraiture, it is

not the sitter as a mere

face and figure that makes

the final significance of the

work ; the external aspect

of the man is but a symbol

and manifestation of the

“aspiring original within.’r

In our approach to a

portrait, therefore, we seek

in this record of external

aspect an expression of

personality. We reckon

with the painter’s tech-

nique—his ability to draw,

his feeling for colour, his

by orlando sense of decorative rela-

rouland tions—not as the evidence

cxxv