What Tale does this 'Tapestry Tell ?

FROM A BOOK OF HOURS

must be the picture of David and Bath-sheba

which shows the king on the roof. The mediaeval

artist had-never seen the roof of an Oriental house,

flat, parapetted and the resort of the household “in

eventide,” which was the hour when David saw

Bath-sheba. Mediaeval (European) roofs were

steep and impossible to walk upon, and hence the

mediaeval artist almost invariably shows David

looking out of an upper window or out of a porch

or balcony. In the background of the tapestry

there is shown, interestingly enough, the roof of a

mediaeval house, and it may be taken as some

expression by the artist as to why it was impossi-

ble for him to represent David walking upon a

roof. The roof is shown between the canopy of

the fountain and the column of the porch that

David is on. A typical mediaeval housetop may be

seen in Diirer’s well-known print of the Prodigal

among the Swine. In fact, I have seen many pic-

tures of David and Bath-sheba, but I do not recall

any wherein the artist has put David upon the

roof of a mediaeval house.

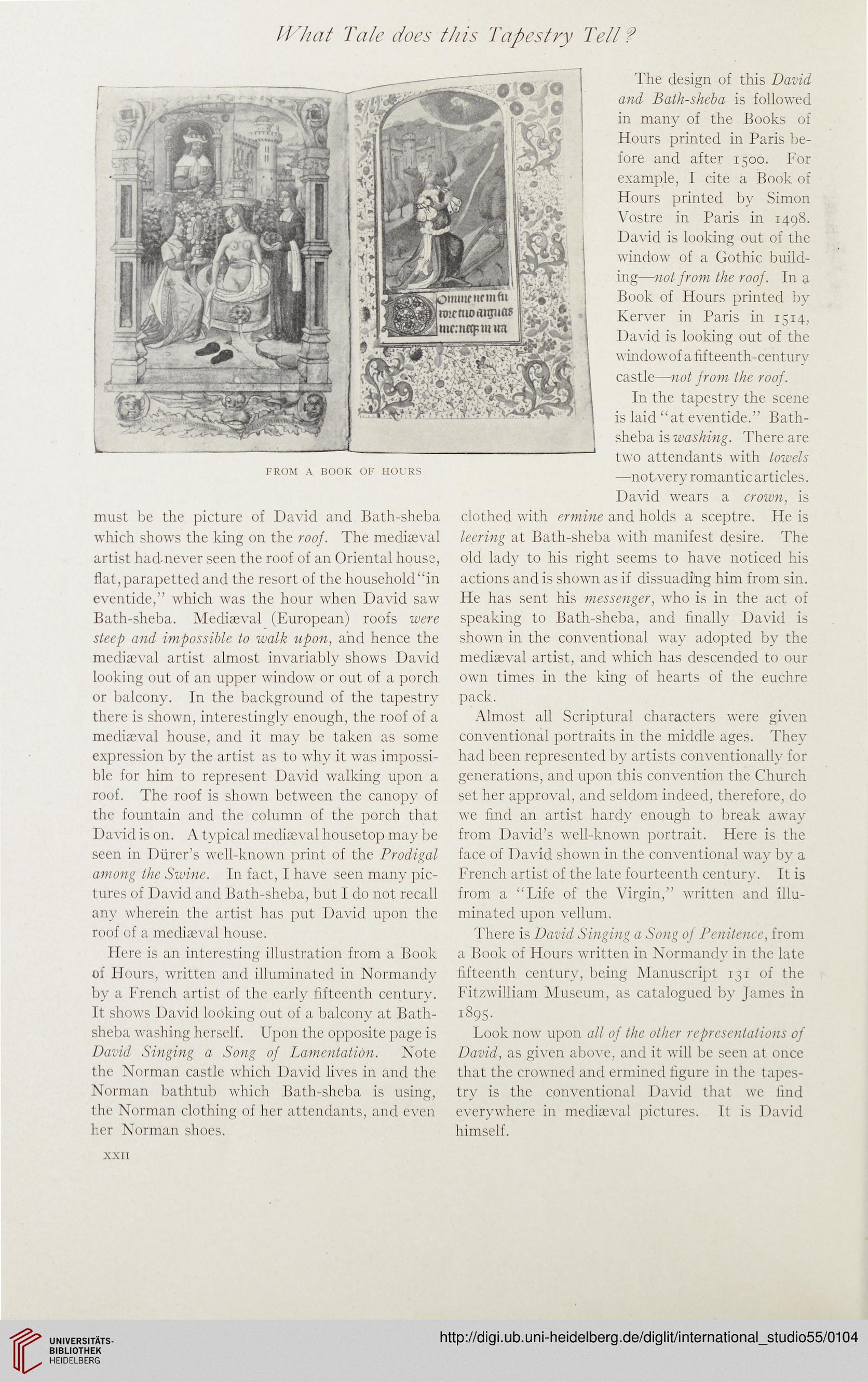

Here is an interesting illustration from a Book

of Hours, written and illuminated in Normandy

by a French artist of the early fifteenth century.

It shows David looking out of a balcony at Bath-

sheba washing herself. Upon the opposite page is

David Singing a Song of Lamentation. Note

the Norman castle which David lives in and the

Norman bathtub which Bath-sheba is using,

the Norman clothing of her attendants, and even

her Norman shoes.

The design of this David

and Bath-sheba is followed

in many of the Books of

Hours printed in Paris be-

fore and after 1500. For

example, I cite a Book of

Hours printed by Simon

Vostre in Paris in 1498.

David is looking out of the

window of a Gothic build-

ing—not from the roof. In a

Book of Hours printed by

Kerver in Paris in 1514,

David is looking out of the

windowof a fifteenth-century

castle—not from the roof.

In the tapestry the scene

is laid “at eventide.” Bath-

sheba is washing. There are

two attendants with towels

—not-very roman tic articles.

David wears a crown, is

clothed with ermine and holds a sceptre. He is

leering at Bath-sheba with manifest desire. The

old lady to his right seems to have noticed his

actions and is shown as if dissuading him from sin.

He has sent his messenger, who is in the act of

speaking to Bath-sheba, and finally David is

shown in the conventional way adopted by the

mediaeval artist, and which has descended to our

own times in the king of hearts of the euchre

pack.

Almost all Scriptural characters were given

conventional portraits in the middle ages. They

had been represented by artists conventionally for

generations, and upon this convention the Church

set her approval, and seldom indeed, therefore, do

we find an artist hardy enough to break away

from David’s well-known portrait. Here is the

face of David shown in the conventional way by a

French artist of the late fourteenth century. It is

from a “Life of the Virgin,” written and illu-

minated upon vellum.

There is David Singing a Song of Penitence, from

a Book of Hours written in Normandy in the late

fifteenth century, being Manuscript 131 of the

Fitzwilliam Museum, as catalogued by James in

1895.

Look now upon all of the other representations of

David, as given above, and it will be seen at once

that the crowned and ermined figure in the tapes-

try is the conventional David that we find

everywhere in mediaeval pictures. It is David

himself.

XXII

FROM A BOOK OF HOURS

must be the picture of David and Bath-sheba

which shows the king on the roof. The mediaeval

artist had-never seen the roof of an Oriental house,

flat, parapetted and the resort of the household “in

eventide,” which was the hour when David saw

Bath-sheba. Mediaeval (European) roofs were

steep and impossible to walk upon, and hence the

mediaeval artist almost invariably shows David

looking out of an upper window or out of a porch

or balcony. In the background of the tapestry

there is shown, interestingly enough, the roof of a

mediaeval house, and it may be taken as some

expression by the artist as to why it was impossi-

ble for him to represent David walking upon a

roof. The roof is shown between the canopy of

the fountain and the column of the porch that

David is on. A typical mediaeval housetop may be

seen in Diirer’s well-known print of the Prodigal

among the Swine. In fact, I have seen many pic-

tures of David and Bath-sheba, but I do not recall

any wherein the artist has put David upon the

roof of a mediaeval house.

Here is an interesting illustration from a Book

of Hours, written and illuminated in Normandy

by a French artist of the early fifteenth century.

It shows David looking out of a balcony at Bath-

sheba washing herself. Upon the opposite page is

David Singing a Song of Lamentation. Note

the Norman castle which David lives in and the

Norman bathtub which Bath-sheba is using,

the Norman clothing of her attendants, and even

her Norman shoes.

The design of this David

and Bath-sheba is followed

in many of the Books of

Hours printed in Paris be-

fore and after 1500. For

example, I cite a Book of

Hours printed by Simon

Vostre in Paris in 1498.

David is looking out of the

window of a Gothic build-

ing—not from the roof. In a

Book of Hours printed by

Kerver in Paris in 1514,

David is looking out of the

windowof a fifteenth-century

castle—not from the roof.

In the tapestry the scene

is laid “at eventide.” Bath-

sheba is washing. There are

two attendants with towels

—not-very roman tic articles.

David wears a crown, is

clothed with ermine and holds a sceptre. He is

leering at Bath-sheba with manifest desire. The

old lady to his right seems to have noticed his

actions and is shown as if dissuading him from sin.

He has sent his messenger, who is in the act of

speaking to Bath-sheba, and finally David is

shown in the conventional way adopted by the

mediaeval artist, and which has descended to our

own times in the king of hearts of the euchre

pack.

Almost all Scriptural characters were given

conventional portraits in the middle ages. They

had been represented by artists conventionally for

generations, and upon this convention the Church

set her approval, and seldom indeed, therefore, do

we find an artist hardy enough to break away

from David’s well-known portrait. Here is the

face of David shown in the conventional way by a

French artist of the late fourteenth century. It is

from a “Life of the Virgin,” written and illu-

minated upon vellum.

There is David Singing a Song of Penitence, from

a Book of Hours written in Normandy in the late

fifteenth century, being Manuscript 131 of the

Fitzwilliam Museum, as catalogued by James in

1895.

Look now upon all of the other representations of

David, as given above, and it will be seen at once

that the crowned and ermined figure in the tapes-

try is the conventional David that we find

everywhere in mediaeval pictures. It is David

himself.

XXII