The Resuscitation of a Dead Art

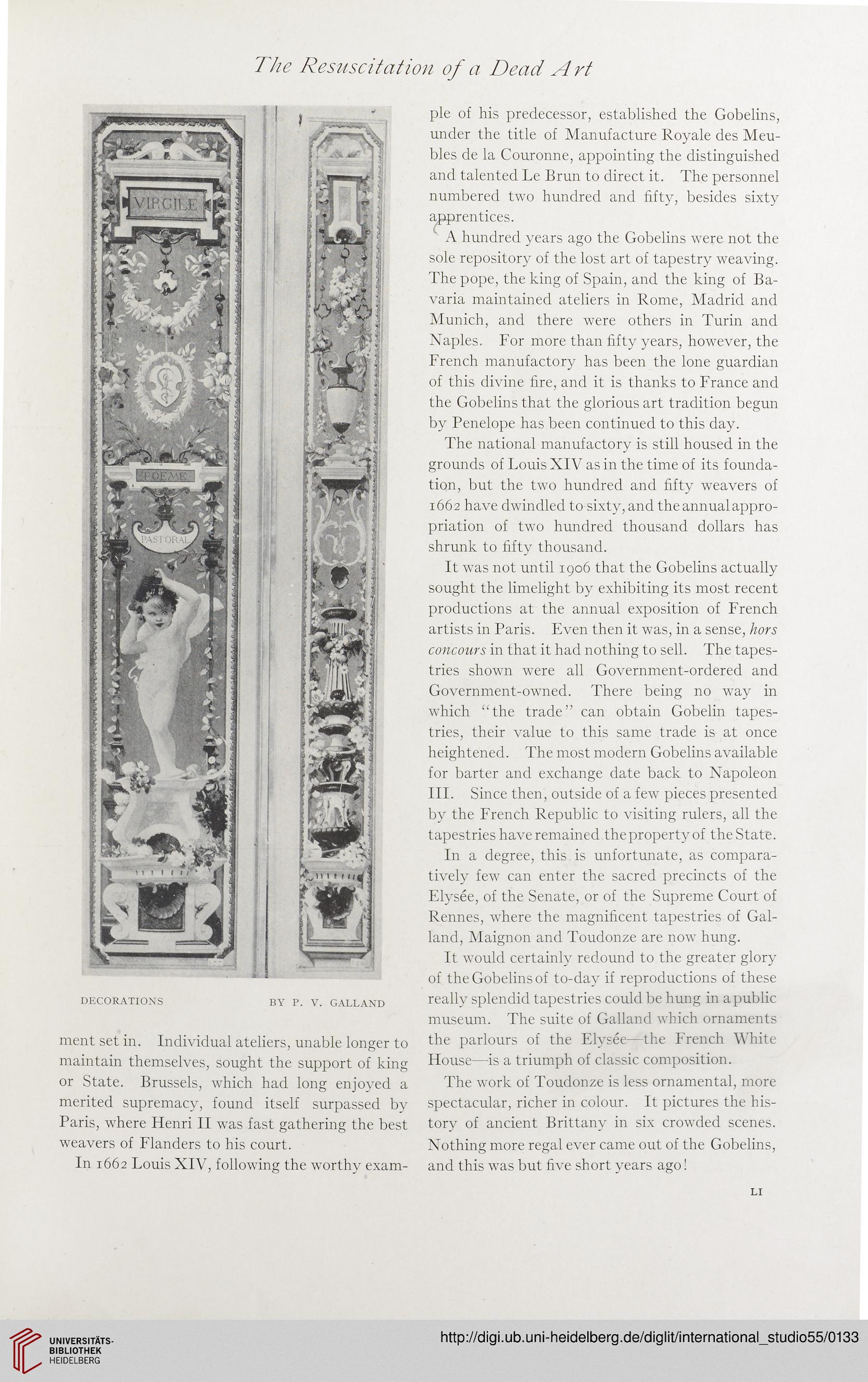

DECORATIONS

BY P. V. GALLAND

ment set in. Individual ateliers, unable longer to

maintain themselves, sought the support of king

or State. Brussels, which had long enjoyed a

merited supremacy, found itself surpassed by

Paris, where Henri II was fast gathering the best

weavers of Flanders to his court.

In 1662 Louis XIV, following the worthy exam-

ple of his predecessor, established the Gobelins,

under the title of Manufacture Royale des Meu-

bles de la Couronne, appointing the distinguished

and talented Le Brun to direct it. The personnel

numbered two hundred and fifty, besides sixty

apprentices.

A hundred years ago the Gobelins were not the

sole repository of the lost art of tapestry weaving.

The pope, the king of Spain, and the king of Ba-

varia maintained ateliers in Rome, Madrid and

Munich, and there were others in Turin and

Naples. For more than fifty years, however, the

French manufactory has been the lone guardian

of this divine fire, and it is thanks to France and

the Gobelins that the glorious art tradition begun

by Penelope has been continued to this day.

The national manufactory is still housed in the

grounds of Louis XIV as in the time of its founda-

tion, but the two hundred and fifty weavers of

1662 have dwindled to sixty, and the annual appro-

priation of two hundred thousand dollars has

shrunk to fifty thousand.

It was not until 1906 that the Gobelins actually

sought the limelight by exhibiting its most recent

productions at the annual exposition of French

artists in Paris. Even then it was, in a sense, hors

cone ours in that it had nothing to sell. The tapes-

tries shown were all Government-ordered and

Government-owned. There being no way in

which “the trade” can obtain Gobelin tapes-

tries, their value to this same trade is at once

heightened. The most modern Gobelins available

for barter and exchange date back to Napoleon

III. Since then, outside of a few pieces presented

by the French Republic to visiting rulers, all the

tapestries have remained the property of the State.

In a degree, this is unfortunate, as compara-

tively few can enter the sacred precincts of the

Elysee, of the Senate, or of the Supreme Court of

Rennes, where the magnificent tapestries of Gal-

land, Maignon and Toudonze are now hung.

It would certainly redound to the greater glory

of the Gobelins of to-day if reproductions of these

really splendid tapestries could be hung in a public

museum. The suite of Galland which ornaments

the parlours of the Elysee—the French White

House—is a triumph of classic composition.

The work of Toudonze is less ornamental, more

spectacular, richer in colour. It pictures the his-

tory of ancient Brittany in six crowded scenes.

Nothing more regal ever came out of the Gobelins,

and this was but five short years ago!

LI

DECORATIONS

BY P. V. GALLAND

ment set in. Individual ateliers, unable longer to

maintain themselves, sought the support of king

or State. Brussels, which had long enjoyed a

merited supremacy, found itself surpassed by

Paris, where Henri II was fast gathering the best

weavers of Flanders to his court.

In 1662 Louis XIV, following the worthy exam-

ple of his predecessor, established the Gobelins,

under the title of Manufacture Royale des Meu-

bles de la Couronne, appointing the distinguished

and talented Le Brun to direct it. The personnel

numbered two hundred and fifty, besides sixty

apprentices.

A hundred years ago the Gobelins were not the

sole repository of the lost art of tapestry weaving.

The pope, the king of Spain, and the king of Ba-

varia maintained ateliers in Rome, Madrid and

Munich, and there were others in Turin and

Naples. For more than fifty years, however, the

French manufactory has been the lone guardian

of this divine fire, and it is thanks to France and

the Gobelins that the glorious art tradition begun

by Penelope has been continued to this day.

The national manufactory is still housed in the

grounds of Louis XIV as in the time of its founda-

tion, but the two hundred and fifty weavers of

1662 have dwindled to sixty, and the annual appro-

priation of two hundred thousand dollars has

shrunk to fifty thousand.

It was not until 1906 that the Gobelins actually

sought the limelight by exhibiting its most recent

productions at the annual exposition of French

artists in Paris. Even then it was, in a sense, hors

cone ours in that it had nothing to sell. The tapes-

tries shown were all Government-ordered and

Government-owned. There being no way in

which “the trade” can obtain Gobelin tapes-

tries, their value to this same trade is at once

heightened. The most modern Gobelins available

for barter and exchange date back to Napoleon

III. Since then, outside of a few pieces presented

by the French Republic to visiting rulers, all the

tapestries have remained the property of the State.

In a degree, this is unfortunate, as compara-

tively few can enter the sacred precincts of the

Elysee, of the Senate, or of the Supreme Court of

Rennes, where the magnificent tapestries of Gal-

land, Maignon and Toudonze are now hung.

It would certainly redound to the greater glory

of the Gobelins of to-day if reproductions of these

really splendid tapestries could be hung in a public

museum. The suite of Galland which ornaments

the parlours of the Elysee—the French White

House—is a triumph of classic composition.

The work of Toudonze is less ornamental, more

spectacular, richer in colour. It pictures the his-

tory of ancient Brittany in six crowded scenes.

Nothing more regal ever came out of the Gobelins,

and this was but five short years ago!

LI