Japanese Flower Arrangement

uses, all concern regarding their previous

growth, their disposal on stem or branch, the

leafage peculiar to them, and their character-

istic locality, or surroundings in natural landscape,

ceases; their individual or collective beauty of

shape and colour, their softness and fragrance, alone

receive attention. Even the exquisiteness of their

delicate shapes is often lost by the practice of closely

massing them together, and they become simply

a chaos of soft colour. The greenery introduced

to enhance the colour effect has rarely any connec-

tion with the blossoms employed, being selected

for its own grace of outline or richness of verdure.

The Japanese proceeds in an entirely different

manner. To him it is more difficult to dissociate

the charm that he finds in flowers from their rela-

tion to stem and leafage, from their functions in

landscape, from all, in short, that contributes to

their vitality, growth, and attractiveness when

blooming in a natural state. He is, perhaps, a

closer observer of Nature and of the details of

natural scenery ; but however this may be, a blossom

to him is a mere fragment, a morsel of beautiful

plumage, unless he can associate it in his mind

with the vegetation to which it belongs. The

gnarled trunk and straight shoots of the plum-tree,

the arched sweep of the kerria sprays, or the stiff

blades of the iris, are all to him essential to the

enjoyment of these particular flowers. Influenced

by these proclivities, the designer with flowers seeks

first to convey a suggestion of natural growth ; his

composition must, above all things, possess an

appearance of vitality,

With this object, the cuttings employed are on a

larger and more comprehensive scale than those

used for the European bouquet. They consist of

long leaf or flower-clad stems and sprays, and often

of thick branches. They are yet, strictly speaking,

but fragments of larger and more intricate growths ;

and, as such, they cannot present without treat-

ment the true characteristics of the complete plant

or tree which it is the purpose of the designer to

portray in his compositions. The twigs, sprays, and

lateral branches of a tree will have qualities of line

and form distinct from those of the main trunk, and

it is mostly by means of the former members that

the impression of the parent growth is to be con-

veyed. It is here that art comes to his aid, and,

though the expression may seem somewhat para-

doxical, by its artificial treatment of natural

material, aims at making it appear more natural, or,

rather, at making it suggestive of more complete

Nature.

Amid the redundancy and apparent confusion of

vegetable growth, the artist perceives certain pre-

vailing laws of line, of ramification, and of group-

ing ; and it is upon his interpretation of these that

he bases the conventional rules of his art. He

carefully discards certain forms which, though

abounding in Nature, are, to his discriminating

observation, indicative of accident or deformity.

For, whereas Nature, in her abundance, provides

compensation for such vagaries, he perceives that

in his abbreviated and impressionist productions

such failings would stand out uncondoned.

The arranger of flowers, therefore, takes certain

lines which to him briefly express the power, beauty,

and balance of growth. To some extent his

analysis resembles that which our own mediaeval

designers have applied to the decoration of archi-

tecture. The sweeping curves, ramifications, and

spirals of the arabesque show the same powerful

radial lines and the same balance of inequalities,

opposed to geometric symmetry, that are discover-

able in the "radicals" of the Japanese flower

arrangement.

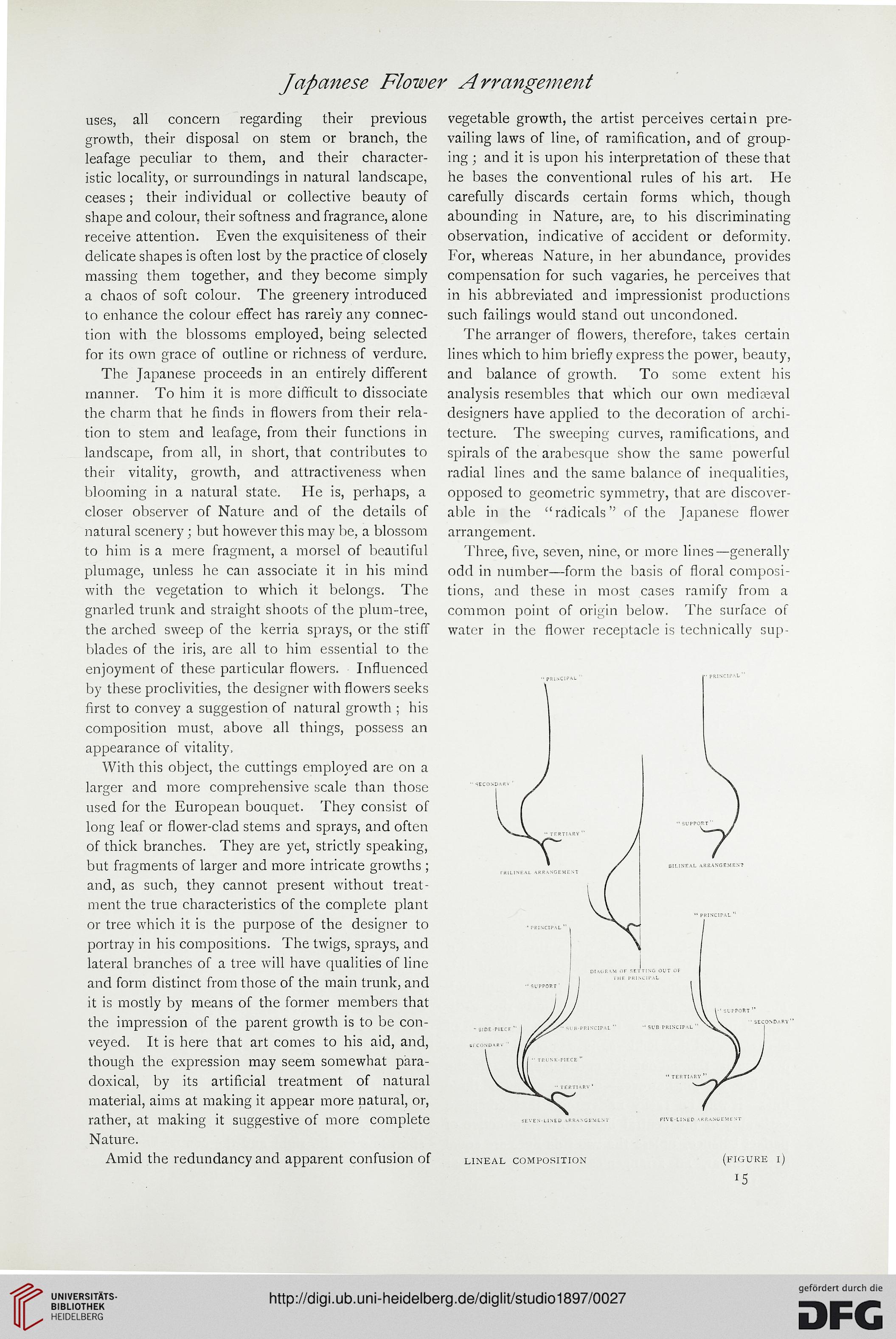

Three, five, seven, nine, or more lines—generally

odd in number—form the basis of floral composi-

tions, and these in most cases ramify from a

common point of origin below. The surface of

water in the flower receptacle is technically sup-

■EVEN-UNED ARRA\GtMLM FIVE-LINED *. P. RANti EM E '-'T

LINEAL COMPOSITION (FIGURE I)

x5

uses, all concern regarding their previous

growth, their disposal on stem or branch, the

leafage peculiar to them, and their character-

istic locality, or surroundings in natural landscape,

ceases; their individual or collective beauty of

shape and colour, their softness and fragrance, alone

receive attention. Even the exquisiteness of their

delicate shapes is often lost by the practice of closely

massing them together, and they become simply

a chaos of soft colour. The greenery introduced

to enhance the colour effect has rarely any connec-

tion with the blossoms employed, being selected

for its own grace of outline or richness of verdure.

The Japanese proceeds in an entirely different

manner. To him it is more difficult to dissociate

the charm that he finds in flowers from their rela-

tion to stem and leafage, from their functions in

landscape, from all, in short, that contributes to

their vitality, growth, and attractiveness when

blooming in a natural state. He is, perhaps, a

closer observer of Nature and of the details of

natural scenery ; but however this may be, a blossom

to him is a mere fragment, a morsel of beautiful

plumage, unless he can associate it in his mind

with the vegetation to which it belongs. The

gnarled trunk and straight shoots of the plum-tree,

the arched sweep of the kerria sprays, or the stiff

blades of the iris, are all to him essential to the

enjoyment of these particular flowers. Influenced

by these proclivities, the designer with flowers seeks

first to convey a suggestion of natural growth ; his

composition must, above all things, possess an

appearance of vitality,

With this object, the cuttings employed are on a

larger and more comprehensive scale than those

used for the European bouquet. They consist of

long leaf or flower-clad stems and sprays, and often

of thick branches. They are yet, strictly speaking,

but fragments of larger and more intricate growths ;

and, as such, they cannot present without treat-

ment the true characteristics of the complete plant

or tree which it is the purpose of the designer to

portray in his compositions. The twigs, sprays, and

lateral branches of a tree will have qualities of line

and form distinct from those of the main trunk, and

it is mostly by means of the former members that

the impression of the parent growth is to be con-

veyed. It is here that art comes to his aid, and,

though the expression may seem somewhat para-

doxical, by its artificial treatment of natural

material, aims at making it appear more natural, or,

rather, at making it suggestive of more complete

Nature.

Amid the redundancy and apparent confusion of

vegetable growth, the artist perceives certain pre-

vailing laws of line, of ramification, and of group-

ing ; and it is upon his interpretation of these that

he bases the conventional rules of his art. He

carefully discards certain forms which, though

abounding in Nature, are, to his discriminating

observation, indicative of accident or deformity.

For, whereas Nature, in her abundance, provides

compensation for such vagaries, he perceives that

in his abbreviated and impressionist productions

such failings would stand out uncondoned.

The arranger of flowers, therefore, takes certain

lines which to him briefly express the power, beauty,

and balance of growth. To some extent his

analysis resembles that which our own mediaeval

designers have applied to the decoration of archi-

tecture. The sweeping curves, ramifications, and

spirals of the arabesque show the same powerful

radial lines and the same balance of inequalities,

opposed to geometric symmetry, that are discover-

able in the "radicals" of the Japanese flower

arrangement.

Three, five, seven, nine, or more lines—generally

odd in number—form the basis of floral composi-

tions, and these in most cases ramify from a

common point of origin below. The surface of

water in the flower receptacle is technically sup-

■EVEN-UNED ARRA\GtMLM FIVE-LINED *. P. RANti EM E '-'T

LINEAL COMPOSITION (FIGURE I)

x5