H. H. La Thangue and his Work

to a spot whose complete isolation was, perhaps, nature—is eminently rational, and, indeed, so far as

only possible to a man just beginning married life, it goes, is open to no question. The painter goes

After a time, on the invitation of Mr. James out into the world, country or town, according to his

Charles, he visited Bosham, in Sussex, and ulti- choice, and paints his subject in its own environ-

mately settled in a farmhouse near that ancient ment—the gleaner in the field, the shepherd in the

village, where he now lives and is likely to remain, fold, or, if you like, the laundress at her stove, or

Having followed Mr. La Thangue through the my lady in her boudoir. Truth of ensemble is, I

years of his hard-working studentship, and noted should say, the main aesthetic principle, and to

his early and confirmed conviction in favour of arrive at this it is necessary to have the dramatis

persona of the picture on the

r q scene where the action takes

place. It used to be said,

and some still repeat the

paradox, that a pupil can

paint a head, but only a

master can paint a back-

ground. It would be easy to

take such a statement more

seriously than it is intended,

but I often wonder whether

the main difficulty the para-

dox suggests is in painting a

background which is not

behind the figure—in adapt-

ing, or, as we say in the

studio, in " faking" it. How-

ever that may be, Mr. La

Thangue is free of any such

difficulty. He invariably

places his model by its back-

ground or surrounding —

barn or drawing-room, as the

case may be. He tells me

that he is now no nearer

doing anything chic than he

was at the earliest stages

of his career. If he had

elected to live in London or

any other city he would have

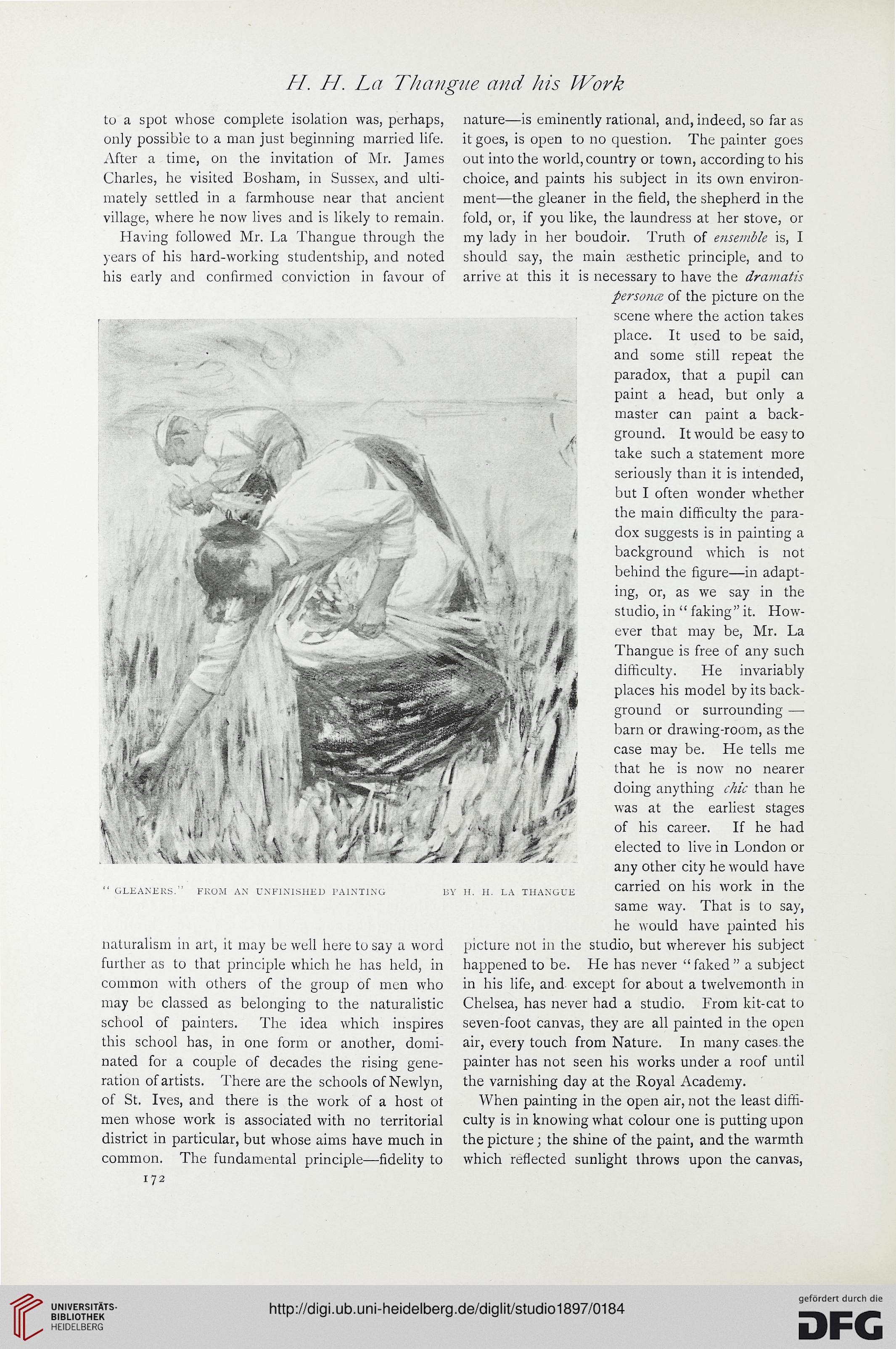

" gleaners." from an dnfinished painting by ii. h. la TiiAXGUK carried on his work in the

same way. That is to say,

he would have painted his

naturalism in art, it may be well here to say a word picture not in the studio, but wherever his subject

further as to that principle which he has held, in happened to be. He has never " faked " a subject

common with others of the group of men who in his life, and except for about a twelvemonth in

may be classed as belonging to the naturalistic Chelsea, has never had a studio. From kit-cat to

school of painters. The idea which inspires seven-foot canvas, they are all painted in the open

this school has, in one form or another, domi- air, every touch from Nature. In many cases, the

nated for a couple of decades the rising gene- painter has not seen his works under a roof until

ration of artists. There are the schools of Newly n, the varnishing day at the Royal Academy,

of St. Ives, and there is the work of a host ot When painting in the open air, not the least diffi-

men whose work is associated with no territorial culty is in knowing what colour one is putting upon

district in particular, but whose aims have much in the picture; the shine of the paint, and the warmth

common. The fundamental principle—fidelity to which reflected sunlight throws upon the canvas,

172

to a spot whose complete isolation was, perhaps, nature—is eminently rational, and, indeed, so far as

only possible to a man just beginning married life, it goes, is open to no question. The painter goes

After a time, on the invitation of Mr. James out into the world, country or town, according to his

Charles, he visited Bosham, in Sussex, and ulti- choice, and paints his subject in its own environ-

mately settled in a farmhouse near that ancient ment—the gleaner in the field, the shepherd in the

village, where he now lives and is likely to remain, fold, or, if you like, the laundress at her stove, or

Having followed Mr. La Thangue through the my lady in her boudoir. Truth of ensemble is, I

years of his hard-working studentship, and noted should say, the main aesthetic principle, and to

his early and confirmed conviction in favour of arrive at this it is necessary to have the dramatis

persona of the picture on the

r q scene where the action takes

place. It used to be said,

and some still repeat the

paradox, that a pupil can

paint a head, but only a

master can paint a back-

ground. It would be easy to

take such a statement more

seriously than it is intended,

but I often wonder whether

the main difficulty the para-

dox suggests is in painting a

background which is not

behind the figure—in adapt-

ing, or, as we say in the

studio, in " faking" it. How-

ever that may be, Mr. La

Thangue is free of any such

difficulty. He invariably

places his model by its back-

ground or surrounding —

barn or drawing-room, as the

case may be. He tells me

that he is now no nearer

doing anything chic than he

was at the earliest stages

of his career. If he had

elected to live in London or

any other city he would have

" gleaners." from an dnfinished painting by ii. h. la TiiAXGUK carried on his work in the

same way. That is to say,

he would have painted his

naturalism in art, it may be well here to say a word picture not in the studio, but wherever his subject

further as to that principle which he has held, in happened to be. He has never " faked " a subject

common with others of the group of men who in his life, and except for about a twelvemonth in

may be classed as belonging to the naturalistic Chelsea, has never had a studio. From kit-cat to

school of painters. The idea which inspires seven-foot canvas, they are all painted in the open

this school has, in one form or another, domi- air, every touch from Nature. In many cases, the

nated for a couple of decades the rising gene- painter has not seen his works under a roof until

ration of artists. There are the schools of Newly n, the varnishing day at the Royal Academy,

of St. Ives, and there is the work of a host ot When painting in the open air, not the least diffi-

men whose work is associated with no territorial culty is in knowing what colour one is putting upon

district in particular, but whose aims have much in the picture; the shine of the paint, and the warmth

common. The fundamental principle—fidelity to which reflected sunlight throws upon the canvas,

172