The early Iconographie of the Crowning with Thorns

39

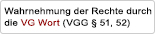

18. St. Augustine Gospels, Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, cod. 286, fol. 125

however clear that Christ’s nimbus is of a different kind than in the other scenes. There Christ has a

crossed nimbus, here instead we have a rayed nimbus, and to judge from the colour reproduction in

Wormald’sbook, also the colour of the gown is different-there it is purple, here it is silvery gray. The two

soldiers following Hirn carry swords or more likely sticks.

Both the rayed and the normal nimbus have a long history which can be followed far back into antiquity,

both in Greece and in the Orient11 * * 14. In late antiquity in Rome the normal nimbus does not seem to have

any special significance except to designate the depictured as a god, hero or personification. The rayed

nimbus, however, was exclusively used as attributes of sun-gods or gods having Connections with the

sun15. The importance of sun-gods, both Hellenistic and Oriental, in Rome is well established, and in the

end of the second Century Marcus Aurelius proclaimed Sol Invictus the highest divinity in the Roman

Empire16. At the time of Constantine the nimbus started to be used in imperial portraits; about the same

time or a little later, it also appeared on Christian monuments, though not as a rule, and in the beginning

only in representations of Christ17.

The cult of the Emperor was intimately connected with Sol Invictus with whom the Emperor wanted to

identify himself18. Erom this connection stems the Strahlenkrone. We find this crown already in portraits

of Alexander, the Seleucide kings and Oriental rulers, and it makes its appearance in Roman imperial

11 On the early history of the nimbus see L. Stephani, Nimbus und Strahlenkrone in den Werken der alten Kunst, Memoires de

l’Academie Imperiale des Sciences de St-Petersbourg, serie VI, Sciences politiques, histoire et philologie, IX, 1859, pp. 359ff.;

A. Krücke, Der Nimbus und verwandte Attribute in der frühchristlichen Kunst, Straßburg 1905; K. Keyssner, Nimbus, in.

Paulys Real-Encyclopädie der klassischen Altertumswissenschaft, XVIII, Stuttgart 1936, col. 591 ff.; E. H. Ramsden, The Halo:

A Fürther Inquiry into its Origin, Burlington Magazine, LXXVII, 1941, p. 123ff.

15 Paulys Real-Encyclopädie, XVIII, col. 612.

16 F. Cumont, La theologie solaire du paganisme romain, Memoires presentes par divers savants ä l’Academie des Inscriptions,

XII, 1909; J. Gage, Apollon Romain, Paris 1955, p. 639f.

17 G. B. Ladner, The so-called Square Nimbus, Mediaeval Studies, III, 1941, p. 35; Krücke, op. cit., pp. 73ff., 101 ff.

18 Gage, op. cit., p. 674,

39

18. St. Augustine Gospels, Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, cod. 286, fol. 125

however clear that Christ’s nimbus is of a different kind than in the other scenes. There Christ has a

crossed nimbus, here instead we have a rayed nimbus, and to judge from the colour reproduction in

Wormald’sbook, also the colour of the gown is different-there it is purple, here it is silvery gray. The two

soldiers following Hirn carry swords or more likely sticks.

Both the rayed and the normal nimbus have a long history which can be followed far back into antiquity,

both in Greece and in the Orient11 * * 14. In late antiquity in Rome the normal nimbus does not seem to have

any special significance except to designate the depictured as a god, hero or personification. The rayed

nimbus, however, was exclusively used as attributes of sun-gods or gods having Connections with the

sun15. The importance of sun-gods, both Hellenistic and Oriental, in Rome is well established, and in the

end of the second Century Marcus Aurelius proclaimed Sol Invictus the highest divinity in the Roman

Empire16. At the time of Constantine the nimbus started to be used in imperial portraits; about the same

time or a little later, it also appeared on Christian monuments, though not as a rule, and in the beginning

only in representations of Christ17.

The cult of the Emperor was intimately connected with Sol Invictus with whom the Emperor wanted to

identify himself18. Erom this connection stems the Strahlenkrone. We find this crown already in portraits

of Alexander, the Seleucide kings and Oriental rulers, and it makes its appearance in Roman imperial

11 On the early history of the nimbus see L. Stephani, Nimbus und Strahlenkrone in den Werken der alten Kunst, Memoires de

l’Academie Imperiale des Sciences de St-Petersbourg, serie VI, Sciences politiques, histoire et philologie, IX, 1859, pp. 359ff.;

A. Krücke, Der Nimbus und verwandte Attribute in der frühchristlichen Kunst, Straßburg 1905; K. Keyssner, Nimbus, in.

Paulys Real-Encyclopädie der klassischen Altertumswissenschaft, XVIII, Stuttgart 1936, col. 591 ff.; E. H. Ramsden, The Halo:

A Fürther Inquiry into its Origin, Burlington Magazine, LXXVII, 1941, p. 123ff.

15 Paulys Real-Encyclopädie, XVIII, col. 612.

16 F. Cumont, La theologie solaire du paganisme romain, Memoires presentes par divers savants ä l’Academie des Inscriptions,

XII, 1909; J. Gage, Apollon Romain, Paris 1955, p. 639f.

17 G. B. Ladner, The so-called Square Nimbus, Mediaeval Studies, III, 1941, p. 35; Krücke, op. cit., pp. 73ff., 101 ff.

18 Gage, op. cit., p. 674,