The Scrip

appropriate to that material. It is also said of him

that he intensely loved the theater, and this, too,

appears in his artificial but delightful arrangements

of figures, and theatrical types. What there was of

realism in his art amounted to very little and con-

sisted in his efforts to emulate Rousseau in the

splendid strength of his tree-forms. He painted

Eastern scenes with a free hand, but he seems not

to have visited any Eastern country. His queer

little Turks or Greeks play blindman’s buff on the

Paris pavements, his Eastern Bazaar is a bit of sheer

fancy; in his Holy Family in the Catherine Wolfe

Collection at the Metropolitan Museum we have

something more akin to reality. The young figure

of the Madonna is homely in its contours and she

sits with a peasant’s unrestraint, but the bloom of

her sturdy beauty is exquisite. The arrangement

of the figures is conventional, but the individual

types are natural, and in the case of the Child dis-

tinguished, and the whole composition floats in a

sunny atmosphere such as Correggio knew how to

evoke. His Spanish origin no doubt gave Diaz

much of that feeling for refinements of color and

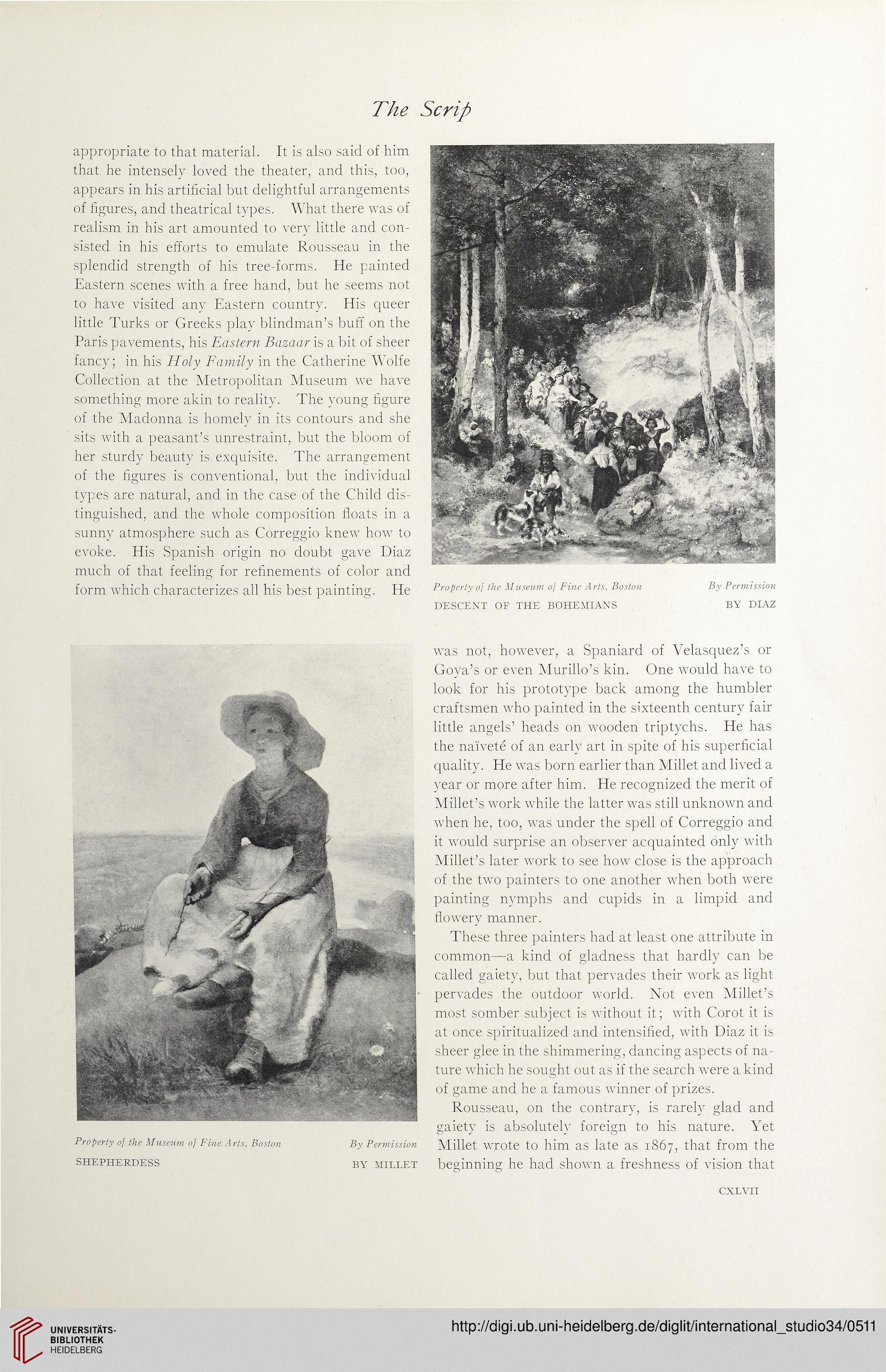

form which characterizes all his best painting. He Properly of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

DESCENT OF THE BOHEMIANS

By Permission

BY DIAZ

was not, however, a Spaniard of Velasquez’s or

Goya’s or even Murillo’s kin. One would have to

look for his prototype back among the humbler

craftsmen who painted in the sixteenth century fair

little angels’ heads on wooden triptychs. He has

the naivete of an early art in spite of his superficial

quality. He was born earlier than Millet and lived a

year or more after him. He recognized the merit of

Millet’s work while the latter was still unknown and

when he, too, was under the spell of Correggio and

it would surprise an observer acquainted only with

Millet’s later work to see how close is the approach

of the two painters to one another when both were

painting nymphs and cupids in a limpid and

flowery manner.

These three painters had at least one attribute in

common—a kind of gladness that hardly can be

called gaiety, but that pervades their work as light

pervades the outdoor world. Not even Millet’s

most somber subject is without it; with Corot it is

at once spiritualized and intensified, with Diaz it is

sheer glee in the shimmering, dancing aspects of na-

ture which he sought out as if the search were a kind

of game and he a famous winner of prizes.

Rousseau, on the contrary, is rarely glad and

gaiety is absolutely foreign to his nature. Yet

Millet wrote to him as late as 1867, that from the

beginning he had shown a freshness of vision that

By Permission

BY MILLET

Properly of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

SHEPHERDESS

CXLVII

appropriate to that material. It is also said of him

that he intensely loved the theater, and this, too,

appears in his artificial but delightful arrangements

of figures, and theatrical types. What there was of

realism in his art amounted to very little and con-

sisted in his efforts to emulate Rousseau in the

splendid strength of his tree-forms. He painted

Eastern scenes with a free hand, but he seems not

to have visited any Eastern country. His queer

little Turks or Greeks play blindman’s buff on the

Paris pavements, his Eastern Bazaar is a bit of sheer

fancy; in his Holy Family in the Catherine Wolfe

Collection at the Metropolitan Museum we have

something more akin to reality. The young figure

of the Madonna is homely in its contours and she

sits with a peasant’s unrestraint, but the bloom of

her sturdy beauty is exquisite. The arrangement

of the figures is conventional, but the individual

types are natural, and in the case of the Child dis-

tinguished, and the whole composition floats in a

sunny atmosphere such as Correggio knew how to

evoke. His Spanish origin no doubt gave Diaz

much of that feeling for refinements of color and

form which characterizes all his best painting. He Properly of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

DESCENT OF THE BOHEMIANS

By Permission

BY DIAZ

was not, however, a Spaniard of Velasquez’s or

Goya’s or even Murillo’s kin. One would have to

look for his prototype back among the humbler

craftsmen who painted in the sixteenth century fair

little angels’ heads on wooden triptychs. He has

the naivete of an early art in spite of his superficial

quality. He was born earlier than Millet and lived a

year or more after him. He recognized the merit of

Millet’s work while the latter was still unknown and

when he, too, was under the spell of Correggio and

it would surprise an observer acquainted only with

Millet’s later work to see how close is the approach

of the two painters to one another when both were

painting nymphs and cupids in a limpid and

flowery manner.

These three painters had at least one attribute in

common—a kind of gladness that hardly can be

called gaiety, but that pervades their work as light

pervades the outdoor world. Not even Millet’s

most somber subject is without it; with Corot it is

at once spiritualized and intensified, with Diaz it is

sheer glee in the shimmering, dancing aspects of na-

ture which he sought out as if the search were a kind

of game and he a famous winner of prizes.

Rousseau, on the contrary, is rarely glad and

gaiety is absolutely foreign to his nature. Yet

Millet wrote to him as late as 1867, that from the

beginning he had shown a freshness of vision that

By Permission

BY MILLET

Properly of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

SHEPHERDESS

CXLVII