The Scrip

left no doubt of the joy he found in nature. Cer-

tainly, his pictures reveal clearly enough his joy in

their creation. None of the 1830 group has more

power over his material. His execution reminds

one of the voice of a trained orator delivering the

finest poetry with a slightly elocutionary emphasis.

But how beautiful a voice it is, what rich depths,

what clear tones, what liquid cadences we have in it!

Millet said to him in his kind desire to comfort

him in the last desperate straits of his life, “You

were from the first the little plant which was des-

tined to become the great oak.” With his native

tact in truth-telling, he had found precisely the right

symbol. Rousseau stands like an oak among his

companions, with obvious strength of will and pur-

pose, with lucidity of style, with a restraint in com-

position, and a great sense of measure and balance.

His early taste for mathematics persists in the

orderly construction of his design, the passion of his

emotional nature that finally broke down his brain

is seen in his powerful color harmonies. He had,

too, the patience that often accompanies such pas-

sion and worked over his pictures, painting and re-

painting them with assiduous care for the final

effect, which invariably was noble. Neglected by

the academies for fourteen years after his first

triumph in 1833, ^ie gained the name of le grand

refuse, and even after the Revolution of 1848, with

its free exhibition at the Louvre, under the guidance

of Rousseau and Dupre, who were both on the

hanging committee, Rousseau’s green pictures were

hailed as “spinach” among the irreverent. He had

in truth a liking for Veronese green that gave a

ringing quality to his foliage and emphasized the

part played by green in his color composition. The

Metropolitan contains many of his pictures, the

finest of them belonging, however, to the Vander-

bilt Loan Collection. Here one may see the Gorges

d’Apremont, the masterpiece that was exhibited in

the Salon of 1859, in which a solemn gloom mingles

with the cool loveliness of early evening.

Dupre, Daubigny and Troyon are the other

names, that are most closely associated with those of

Millet and Corot. Dupre has a power that none of

his companions show of evoking a dramatic mood

of nature and keeping its appearance of realism

without in the slightest degree following literal fact.

His landscapes are as decorative as stained glass

windows and hardly nearer to the texture and light

of nature, yet they stir the imagination to a remem-

brance of nature that justifies them. Looking at

them we paint our own recollected scenes with the

romantic fervor required, and see them true.

Daubigny was a painter of the Normandy land-

scape, but he saw it with the same deep respect for

its secrets and character as the Barbizon men dis-

closed in their very different works. He paints with

a calm vision and a large method and one cannot

look to him for any

quality to support

the title of “roman-

ticist” bestowed in-

discriminately upon

the 1830 School.

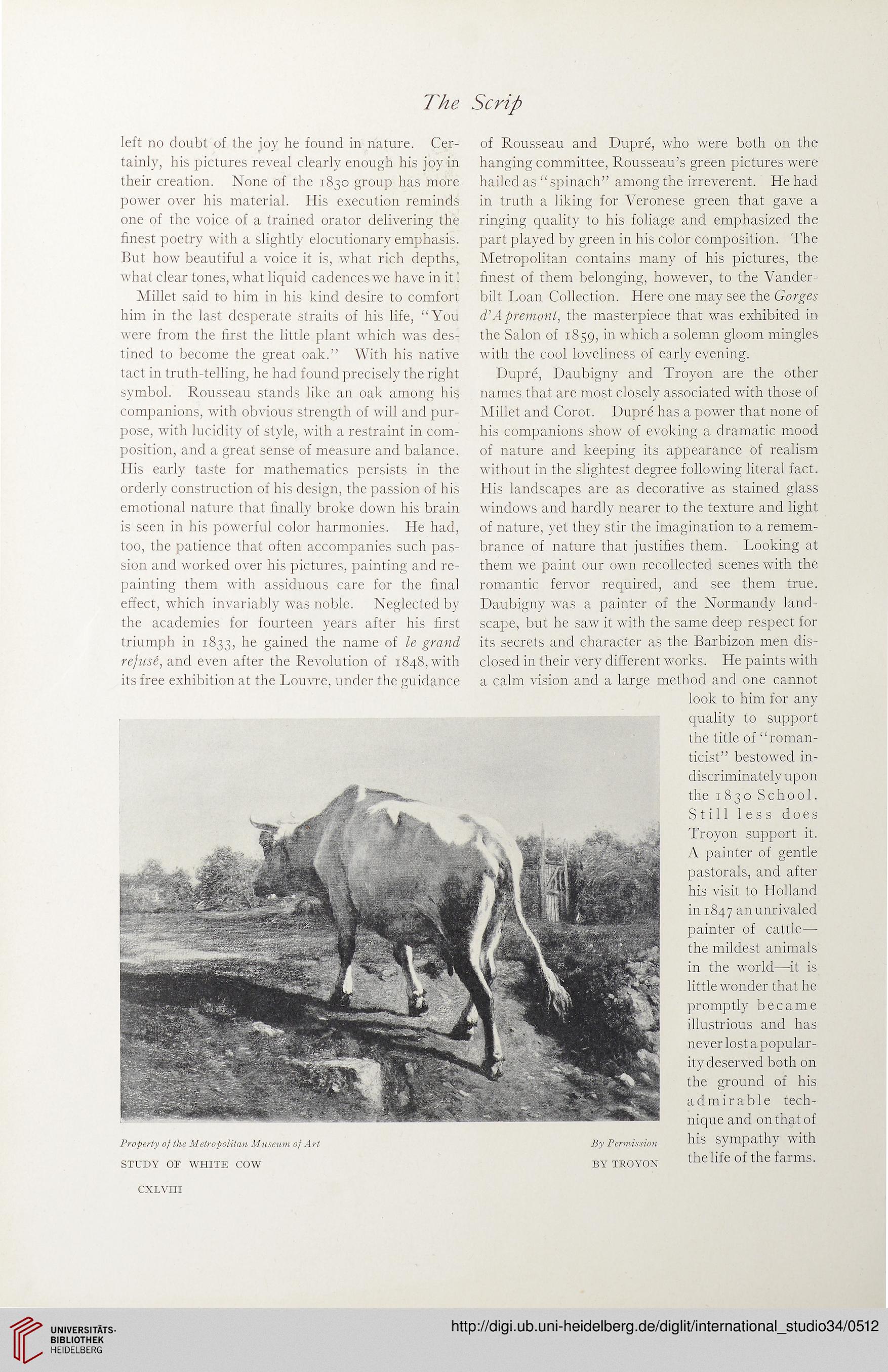

Still less does

Troyon support it.

A painter of gentle

pastorals, and after

his visit to Holland

in 1847 an unrivaled

painter of cattle—

the mildest animals

in the world—it is

little wonder that he

promptly became

illustrious and has

never lost a popular-

ity deserved both on

the ground of his

admirable tech-

nique and on that of

his sympathy with

the life of the farms.

Property oj the Metropolitan Museum oj Art By Permission

STUDY OF WHITE COW BY TROYON

CXLVIII

left no doubt of the joy he found in nature. Cer-

tainly, his pictures reveal clearly enough his joy in

their creation. None of the 1830 group has more

power over his material. His execution reminds

one of the voice of a trained orator delivering the

finest poetry with a slightly elocutionary emphasis.

But how beautiful a voice it is, what rich depths,

what clear tones, what liquid cadences we have in it!

Millet said to him in his kind desire to comfort

him in the last desperate straits of his life, “You

were from the first the little plant which was des-

tined to become the great oak.” With his native

tact in truth-telling, he had found precisely the right

symbol. Rousseau stands like an oak among his

companions, with obvious strength of will and pur-

pose, with lucidity of style, with a restraint in com-

position, and a great sense of measure and balance.

His early taste for mathematics persists in the

orderly construction of his design, the passion of his

emotional nature that finally broke down his brain

is seen in his powerful color harmonies. He had,

too, the patience that often accompanies such pas-

sion and worked over his pictures, painting and re-

painting them with assiduous care for the final

effect, which invariably was noble. Neglected by

the academies for fourteen years after his first

triumph in 1833, ^ie gained the name of le grand

refuse, and even after the Revolution of 1848, with

its free exhibition at the Louvre, under the guidance

of Rousseau and Dupre, who were both on the

hanging committee, Rousseau’s green pictures were

hailed as “spinach” among the irreverent. He had

in truth a liking for Veronese green that gave a

ringing quality to his foliage and emphasized the

part played by green in his color composition. The

Metropolitan contains many of his pictures, the

finest of them belonging, however, to the Vander-

bilt Loan Collection. Here one may see the Gorges

d’Apremont, the masterpiece that was exhibited in

the Salon of 1859, in which a solemn gloom mingles

with the cool loveliness of early evening.

Dupre, Daubigny and Troyon are the other

names, that are most closely associated with those of

Millet and Corot. Dupre has a power that none of

his companions show of evoking a dramatic mood

of nature and keeping its appearance of realism

without in the slightest degree following literal fact.

His landscapes are as decorative as stained glass

windows and hardly nearer to the texture and light

of nature, yet they stir the imagination to a remem-

brance of nature that justifies them. Looking at

them we paint our own recollected scenes with the

romantic fervor required, and see them true.

Daubigny was a painter of the Normandy land-

scape, but he saw it with the same deep respect for

its secrets and character as the Barbizon men dis-

closed in their very different works. He paints with

a calm vision and a large method and one cannot

look to him for any

quality to support

the title of “roman-

ticist” bestowed in-

discriminately upon

the 1830 School.

Still less does

Troyon support it.

A painter of gentle

pastorals, and after

his visit to Holland

in 1847 an unrivaled

painter of cattle—

the mildest animals

in the world—it is

little wonder that he

promptly became

illustrious and has

never lost a popular-

ity deserved both on

the ground of his

admirable tech-

nique and on that of

his sympathy with

the life of the farms.

Property oj the Metropolitan Museum oj Art By Permission

STUDY OF WHITE COW BY TROYON

CXLVIII