Artistic Gardens in Japan

supposed to illustrate in its various parts the fifty-

three posting stations on the great road between

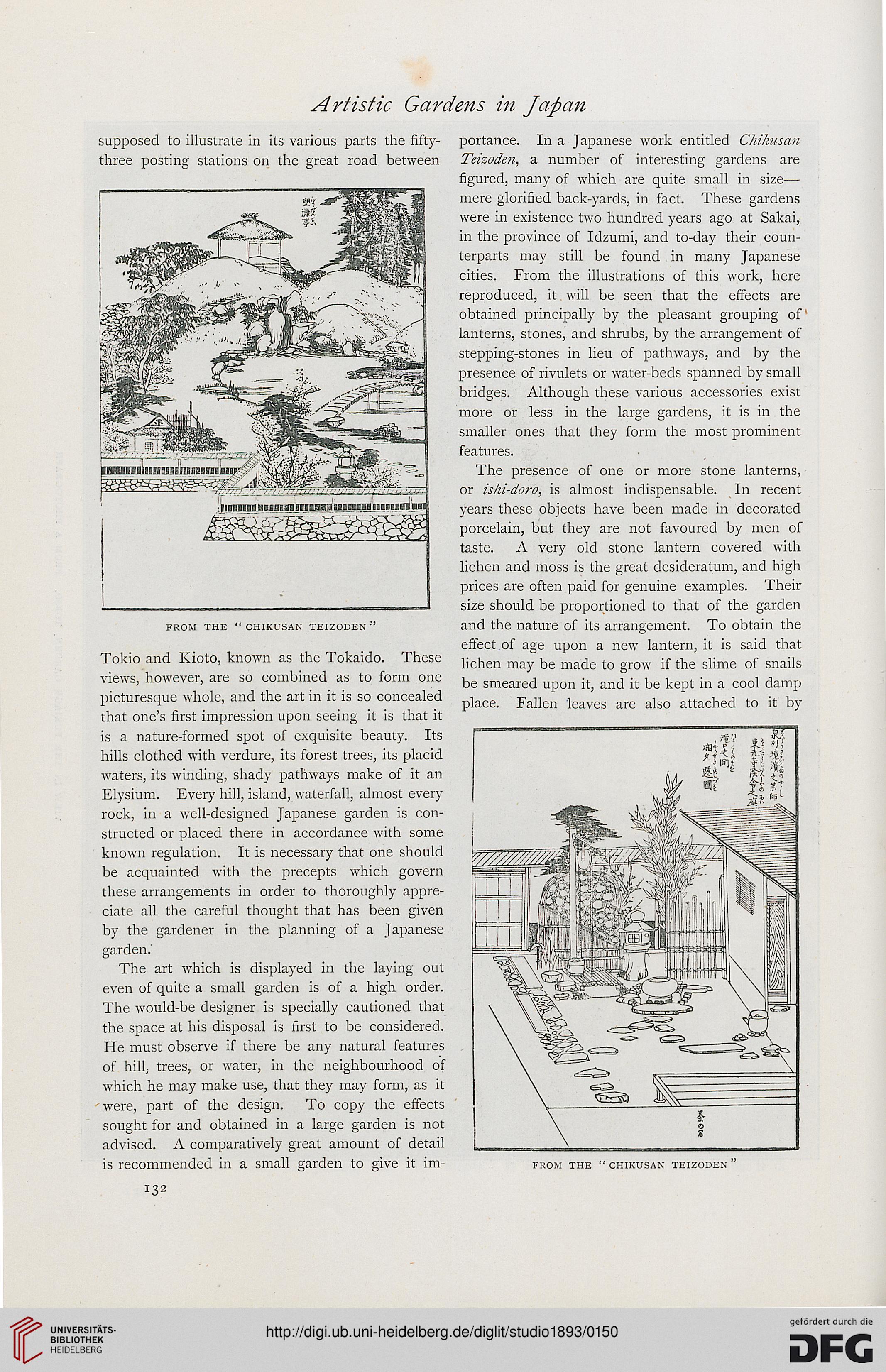

FROM THE " CHIKUSAN TEIZODEN "

Tokio and Kioto, known as the Tokaido. These

views, however, are so combined as to form one

picturesque whole, and the art in it is so concealed

that one's first impression upon seeing it is that it

is a nature-formed spot of exquisite beauty. Its

hills clothed with verdure, its forest trees, its placid

waters, its winding, shady pathways make of it an

Elysium. Every hill, island, waterfall, almost every

rock, in a well-designed Japanese garden is con-

structed or placed there in accordance with some

known regulation. It is necessary that one should

be acquainted with the precepts which govern

these arrangements in order to thoroughly appre-

ciate all the careful thought that has been given

by the gardener in the planning of a Japanese

garden.'

The art which is displayed in the laying out

even of quite a small garden is of a high order.

The would-be designer is specially cautioned that

the space at his disposal is first to be considered.

He must observe if there be any natural features

of hill, trees, or water, in the neighbourhood of

which he may make use, that they may form, as it

were, part of the design. To copy the effects

sought for and obtained in a large garden is not

advised. A comparatively great amount of detail

is recommended in a small garden to give it im-

portance. In a Japanese work entitled Chikusan

Teizoden, a number of interesting gardens are

figured, many of which are quite small in size—

mere glorified back-yards, in fact. These gardens

were in existence two hundred years ago at Sakai,

in the province of Idzumi, and to-day their coun-

terparts may still be found in many Japanese

cities. From the illustrations of this work, here

reproduced, it will be seen that the effects are

obtained principally by the pleasant grouping of

lanterns, stones, and shrubs, by the arrangement of

stepping-stones in lieu of pathways, and by the

presence of rivulets or water-beds spanned by small

bridges. Although these various accessories exist

more or less in the large gardens, it is in the

smaller ones that they form the most prominent

features.

The presence of one or more stone lanterns,

or ishi-doro, is almost indispensable. In recent

years these objects have been made in decorated

porcelain, but they are not favoured by men of

taste. A very old stone lantern covered with

lichen and moss is the great desideratum, and high

prices are often paid for genuine examples. Their

size should be proportioned to that of the garden

and the nature of its arrangement. To obtain the

effect of age upon a new lantern, it is said that

lichen may be made to grow if the slime of snails

be smeared upon it, and it be kept in a cool damp

place. Fallen leaves are also attached to it by

FROM THE "CHIKUSAN TEIZODEN "

supposed to illustrate in its various parts the fifty-

three posting stations on the great road between

FROM THE " CHIKUSAN TEIZODEN "

Tokio and Kioto, known as the Tokaido. These

views, however, are so combined as to form one

picturesque whole, and the art in it is so concealed

that one's first impression upon seeing it is that it

is a nature-formed spot of exquisite beauty. Its

hills clothed with verdure, its forest trees, its placid

waters, its winding, shady pathways make of it an

Elysium. Every hill, island, waterfall, almost every

rock, in a well-designed Japanese garden is con-

structed or placed there in accordance with some

known regulation. It is necessary that one should

be acquainted with the precepts which govern

these arrangements in order to thoroughly appre-

ciate all the careful thought that has been given

by the gardener in the planning of a Japanese

garden.'

The art which is displayed in the laying out

even of quite a small garden is of a high order.

The would-be designer is specially cautioned that

the space at his disposal is first to be considered.

He must observe if there be any natural features

of hill, trees, or water, in the neighbourhood of

which he may make use, that they may form, as it

were, part of the design. To copy the effects

sought for and obtained in a large garden is not

advised. A comparatively great amount of detail

is recommended in a small garden to give it im-

portance. In a Japanese work entitled Chikusan

Teizoden, a number of interesting gardens are

figured, many of which are quite small in size—

mere glorified back-yards, in fact. These gardens

were in existence two hundred years ago at Sakai,

in the province of Idzumi, and to-day their coun-

terparts may still be found in many Japanese

cities. From the illustrations of this work, here

reproduced, it will be seen that the effects are

obtained principally by the pleasant grouping of

lanterns, stones, and shrubs, by the arrangement of

stepping-stones in lieu of pathways, and by the

presence of rivulets or water-beds spanned by small

bridges. Although these various accessories exist

more or less in the large gardens, it is in the

smaller ones that they form the most prominent

features.

The presence of one or more stone lanterns,

or ishi-doro, is almost indispensable. In recent

years these objects have been made in decorated

porcelain, but they are not favoured by men of

taste. A very old stone lantern covered with

lichen and moss is the great desideratum, and high

prices are often paid for genuine examples. Their

size should be proportioned to that of the garden

and the nature of its arrangement. To obtain the

effect of age upon a new lantern, it is said that

lichen may be made to grow if the slime of snails

be smeared upon it, and it be kept in a cool damp

place. Fallen leaves are also attached to it by

FROM THE "CHIKUSAN TEIZODEN "