New Publications

of the doors in the same way, not with any complete No, there is no denying that the early craftsman

scheme of design, but in a somewhat haphazard was often nearly, if not quite, as artful as his latter-

day successors; but if we smile at his indifference

to the canons of " good " art in little matters, such

as the occasional use of stamps and dies, we must

not forget that he had himself to forge his rods and

bars to the sizes he required out of the rough ingots

or " blooms" in which the metal came from the

smelting furnace, instead of posting an order to

Clerkenwell. This fact has no doubt something to

do with the comparatively limited use of those

straight pieces in old ironwork which form such an

important part of the modern smith's stock-in-

trade.

Next in importance and in date after hinges come

the grilles, of which that of St. Swithin at Win-

chester, shown in Fig. i, is such a fine example.

This grille is also a good instance of the supremacy

of the scroll as opposed to the straight rod—the

smith evidently thinking that the same time and

labour involved in producing the latter would be

used to greater advantage in forging curved work.

In spite of their extensive use, there are, however,

very few examples left in England of mediaeval

grilles. Yet it seems to have been a national

characteristic to fence in monuments and other

fig. 3.—from the church door of st. marein, stygia , . ... . .,. ■ ,

0 objects with iron railings or screens in a way that

fashion. Fig. 5 exemplifies this characteristic, and was not nearly so general in other countries,

in some thoroughly typical and very beautiful forged In the following extract, the author notes the

work, shows that where these early

designs are traceable to Nature at

all, they appear to have been in-

spired more by the animal than

by the vegetable world. Mr.

Gardner points out that after mere

rude animal forms, there came the

use of flowers, fruit, and foliage,

and how the foliage very soon

settled down into traditional ren-

derings of the vine, occasionally

varied by the use of the fleur-de-lis

and one or two other motives, until

the thistle, with which we are so

familiar in later Gothic work, was

introduced by the German smiths

of the sixteenth century, and very

freely used by them from that time

onwards.

It will probably be a surprise

to many people, and perhaps rather

a severe shock to those who de-

voutly believe that mechanical aids

to the production of ornament are

entirely the outcome of these two

last degenerate centuries, when

they learn that the constantly re-

curring vine and other leaves, and

the rosettes and fruit forms of

mediaeval ironwork, were for the

most part produced by hammer-

ing the hot iron into prepared dies,

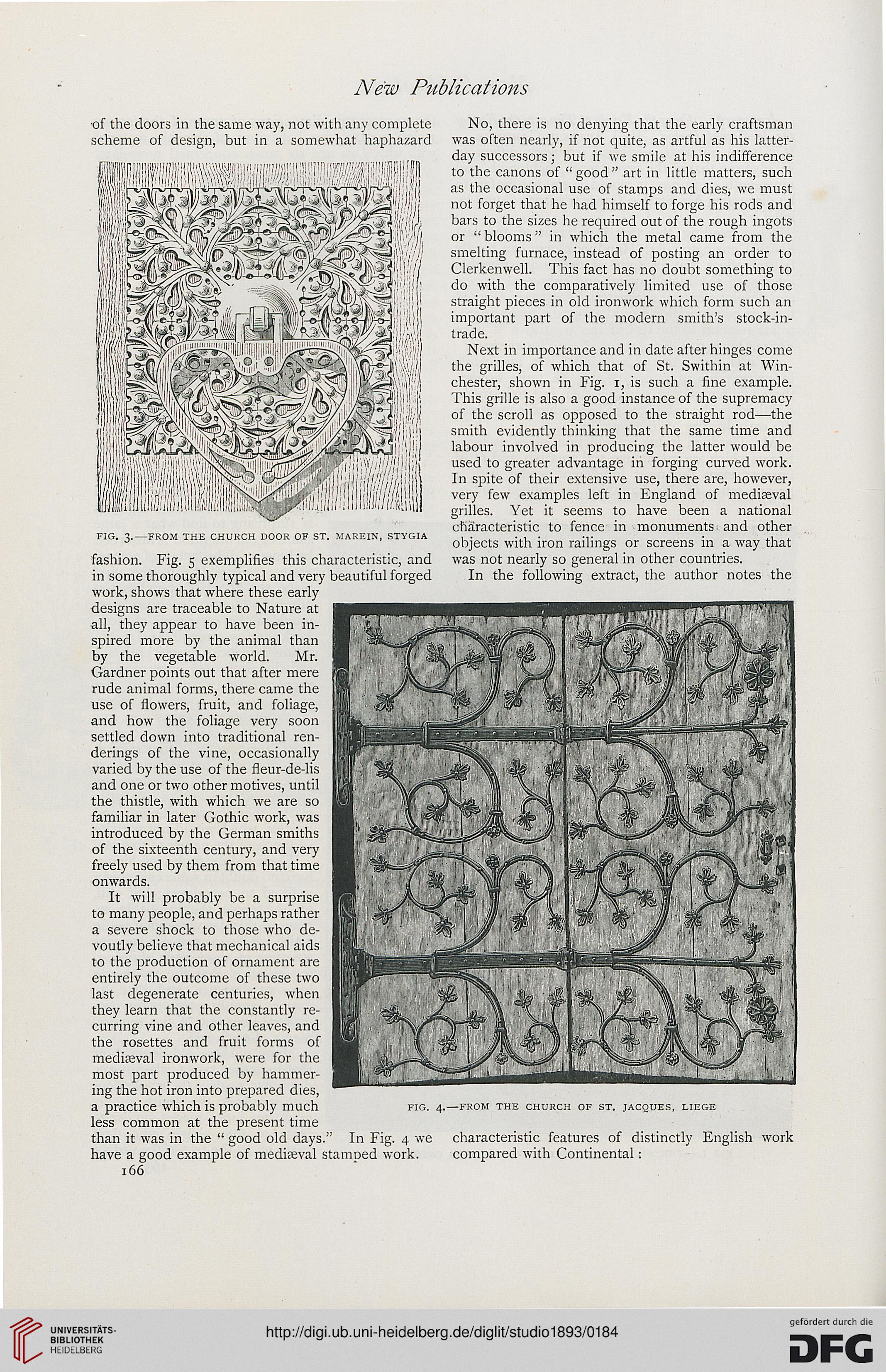

a practice which is probably much fig. 4.—from the church of st. jacques, liege

less common at the present time

than it was in the " good old days." In Fig. 4 we characteristic features of distinctly English work

have a good example of mediaeval stanmed work. compared with Continental ;

166

of the doors in the same way, not with any complete No, there is no denying that the early craftsman

scheme of design, but in a somewhat haphazard was often nearly, if not quite, as artful as his latter-

day successors; but if we smile at his indifference

to the canons of " good " art in little matters, such

as the occasional use of stamps and dies, we must

not forget that he had himself to forge his rods and

bars to the sizes he required out of the rough ingots

or " blooms" in which the metal came from the

smelting furnace, instead of posting an order to

Clerkenwell. This fact has no doubt something to

do with the comparatively limited use of those

straight pieces in old ironwork which form such an

important part of the modern smith's stock-in-

trade.

Next in importance and in date after hinges come

the grilles, of which that of St. Swithin at Win-

chester, shown in Fig. i, is such a fine example.

This grille is also a good instance of the supremacy

of the scroll as opposed to the straight rod—the

smith evidently thinking that the same time and

labour involved in producing the latter would be

used to greater advantage in forging curved work.

In spite of their extensive use, there are, however,

very few examples left in England of mediaeval

grilles. Yet it seems to have been a national

characteristic to fence in monuments and other

fig. 3.—from the church door of st. marein, stygia , . ... . .,. ■ ,

0 objects with iron railings or screens in a way that

fashion. Fig. 5 exemplifies this characteristic, and was not nearly so general in other countries,

in some thoroughly typical and very beautiful forged In the following extract, the author notes the

work, shows that where these early

designs are traceable to Nature at

all, they appear to have been in-

spired more by the animal than

by the vegetable world. Mr.

Gardner points out that after mere

rude animal forms, there came the

use of flowers, fruit, and foliage,

and how the foliage very soon

settled down into traditional ren-

derings of the vine, occasionally

varied by the use of the fleur-de-lis

and one or two other motives, until

the thistle, with which we are so

familiar in later Gothic work, was

introduced by the German smiths

of the sixteenth century, and very

freely used by them from that time

onwards.

It will probably be a surprise

to many people, and perhaps rather

a severe shock to those who de-

voutly believe that mechanical aids

to the production of ornament are

entirely the outcome of these two

last degenerate centuries, when

they learn that the constantly re-

curring vine and other leaves, and

the rosettes and fruit forms of

mediaeval ironwork, were for the

most part produced by hammer-

ing the hot iron into prepared dies,

a practice which is probably much fig. 4.—from the church of st. jacques, liege

less common at the present time

than it was in the " good old days." In Fig. 4 we characteristic features of distinctly English work

have a good example of mediaeval stanmed work. compared with Continental ;

166