New Publications

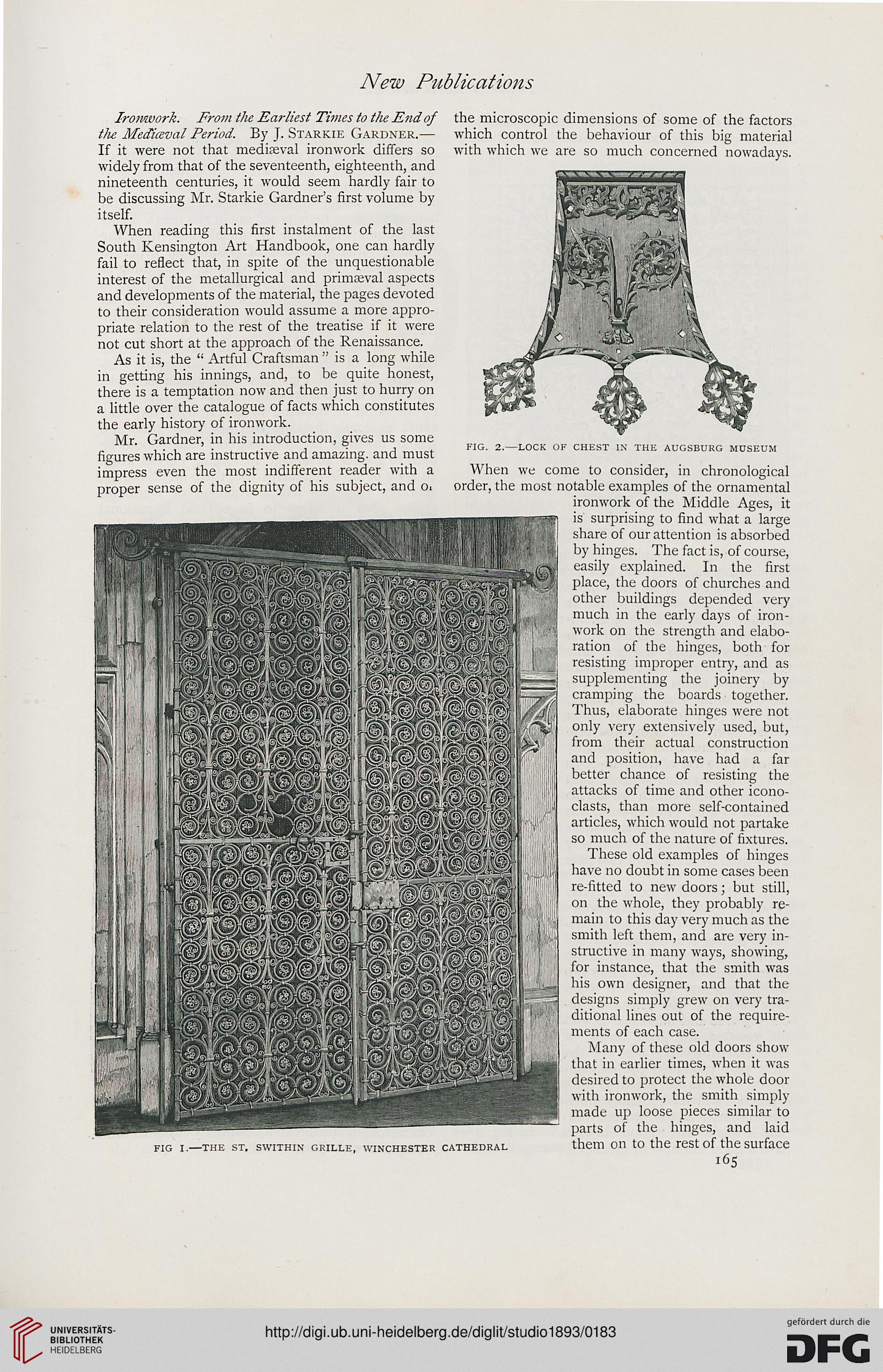

-LOCK OF CHEST IN THE AUGSBURG MUSEUM

Ironwork. From the Earliest Times to the End of the microscopic dimensions of some of the factors

the Medieeval Period. By J. Starkie Gardner.— which control the behaviour of this big material

If it were not that mediaeval ironwork differs so with which we are so much concerned nowadays,

widely from that of the seventeenth, eighteenth, and

nineteenth centuries, it would seem hardly fair to

be discussing Mr. Starkie Gardner's first volume by

itself.

When reading this first instalment of the last

South Kensington Art Handbook, one can hardly

fail to reflect that, in spite of the unquestionable

interest of the metallurgical and primaeval aspects

and developments of the material, the pages devoted

to their consideration would assume a more appro-

priate relation to the rest of the treatise if it were

not cut short at the approach of the Renaissance.

As it is, the " Artful Craftsman " is a long while

in getting his innings, and, to be quite honest,

there is a temptation now and then just to hurry on

a little over the catalogue of facts which constitutes

the early history of ironwork.

Mr. Gardner, in his introduction, gives us some

figures which are instructive and amazing, and must

impress even the most indifferent reader with a When we come to consider, in chronological

proper sense of the dignity of his subject, and Oi order, the most notable examples of the ornamental

ironwork of the Middle Ages, it

is surprising to find what a large

share of our attention is absorbed

by hinges. The fact is, of course,

easily explained. In the first

place, the doors of churches and

other buildings depended very

much in the early days of iron-

work on the strength and elabo-

ration of the hinges, both for

resisting improper entry, and as

supplementing the joinery by

cramping the boards together.

Thus, elaborate hinges were not

only very extensively used, but,

from their actual construction

and position, have had a far

better chance of resisting the

attacks of time and other icono-

clasts, than more self-contained

articles, which would not partake

so much of the nature of fixtures.

These old examples of hinges

have no doubt in some cases been

re-fitted to new doors; but still,

on the whole, they probably re-

main to this day very much as the

smith left them, and are very in-

structive in many ways, showing,

for instance, that the smith was

his own designer, and that the

designs simply grew on very tra-

ditional lines out of the require-

ments of each case.

Many of these old doors show

that in earlier times, when it was

desired to protect the whole door

with ironwork, the smith simply

made up loose pieces similar to

parts of the hinges, and laid

fig i.—the st. swithin grille, Winchester cathedral them on to the rest of the surface

165

-LOCK OF CHEST IN THE AUGSBURG MUSEUM

Ironwork. From the Earliest Times to the End of the microscopic dimensions of some of the factors

the Medieeval Period. By J. Starkie Gardner.— which control the behaviour of this big material

If it were not that mediaeval ironwork differs so with which we are so much concerned nowadays,

widely from that of the seventeenth, eighteenth, and

nineteenth centuries, it would seem hardly fair to

be discussing Mr. Starkie Gardner's first volume by

itself.

When reading this first instalment of the last

South Kensington Art Handbook, one can hardly

fail to reflect that, in spite of the unquestionable

interest of the metallurgical and primaeval aspects

and developments of the material, the pages devoted

to their consideration would assume a more appro-

priate relation to the rest of the treatise if it were

not cut short at the approach of the Renaissance.

As it is, the " Artful Craftsman " is a long while

in getting his innings, and, to be quite honest,

there is a temptation now and then just to hurry on

a little over the catalogue of facts which constitutes

the early history of ironwork.

Mr. Gardner, in his introduction, gives us some

figures which are instructive and amazing, and must

impress even the most indifferent reader with a When we come to consider, in chronological

proper sense of the dignity of his subject, and Oi order, the most notable examples of the ornamental

ironwork of the Middle Ages, it

is surprising to find what a large

share of our attention is absorbed

by hinges. The fact is, of course,

easily explained. In the first

place, the doors of churches and

other buildings depended very

much in the early days of iron-

work on the strength and elabo-

ration of the hinges, both for

resisting improper entry, and as

supplementing the joinery by

cramping the boards together.

Thus, elaborate hinges were not

only very extensively used, but,

from their actual construction

and position, have had a far

better chance of resisting the

attacks of time and other icono-

clasts, than more self-contained

articles, which would not partake

so much of the nature of fixtures.

These old examples of hinges

have no doubt in some cases been

re-fitted to new doors; but still,

on the whole, they probably re-

main to this day very much as the

smith left them, and are very in-

structive in many ways, showing,

for instance, that the smith was

his own designer, and that the

designs simply grew on very tra-

ditional lines out of the require-

ments of each case.

Many of these old doors show

that in earlier times, when it was

desired to protect the whole door

with ironwork, the smith simply

made up loose pieces similar to

parts of the hinges, and laid

fig i.—the st. swithin grille, Winchester cathedral them on to the rest of the surface

165