230

Zeitschrift für historische Waffenkunde.

III. Band.

No. 1098 is a similar armour by the same

Augsburg smith.

No. 1119 is illustrated 011 Fig. V.

Number 474.

On the top of the breastplate is a border

of classic figures and animals; the harness, gene-

rally, is banded boldly in strapwork on a gilt

ground. Tliere is an extra plate over the left

breast and shoulder; and another rises from the

thigh to the centre of the breastplate on that side.

The breastplate, of the peasecod type, is flanged

over the right shoulder; and the lance-rest is small

and folds up. This harness is for Freiturnier

(Free Course), in which a large garde-de-bras

(Stechmäusel) was used in place ofthemanteau

d’armes and the pasgarde1) of Welsches

Gestech. The pasgarde is not present, but the

coude is holed for it.

The difference between welsches Gestech and

Freitournier lay in the circumstance that the

latter was run in the open field or lists, without

a tilt between the jousters. Freiturnier, like

Rennen and Stechen, required more skill and

initiative than did welsches Gestech. The lance

and horse furniture were of the same kind in both

cases, and the body armour of the jousters very

similar; but subject to the interchange of reinforcing

pieces. A suit in the Dresden collection, labelled

v. Holtzendorff is for Freiturnier; as also is that

of Karl Schürft von Schonwert (died 1628). Boeheim

gives an illustration of the last named harness in

liis Waffenkunde as being for das neue welsche

Gestech über das Dill, but I believe this is

not so.

By the commencement of the seventeenth Cen-

tury all the older forms of jousting had fallen into

disuse, with the exception of Freiturnier; and a

sort of skirmish, troop against trepp, called Schar-

mützel. Ringelrennen (running at the ring) also

prevailed greatly, but this game cannot be classecl

as belonging to the tourney.

Number 958.

This suit is without any'very special features

be)mnd the fact that each part is stamped in

numbers, a circumstance suggestive of its having

formed one of a series of armours made to the

same pattern, and possibly of the same size.

A contributing cause to the gradual disuse of

armour was the increasing badness of the fit; and

one sometimes reads of Contemporary complaints

made more especially perhaps after the first half

of the sixteenth Century, of the frequency of badly

fitting plates; which caused great sufifering to the

wearers by reason of the chafing into sores. No

i) This is the real pasgarde (Stechmäuschen); the word

is often used as a clesignation for an upriglit neck guarcl, but

erroneously.

wonder that armour was sometimes thrown away

in a campaign in spite of regulations.

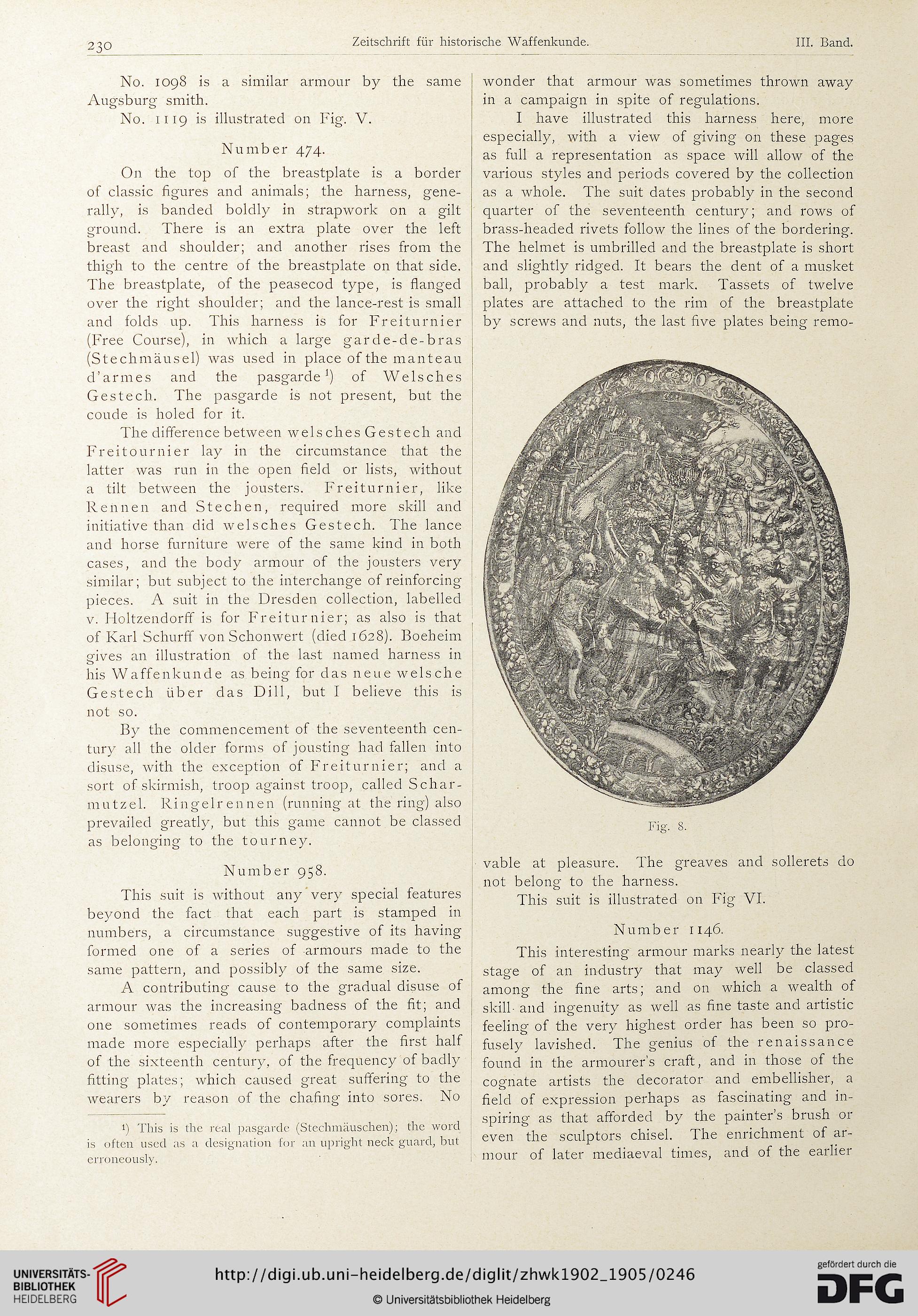

I have illustrated this harness here, more

especially, with a view of giving on these pages

as full a representation as space will allow of the

various styles and periods covered by the collection

as a whole. The suit dates probably in the second

quarter of the seventeenth Century; and rows of

brass-headed rivets follow the lines of the bordering.

The helmet is umbrilled and the breastplate is short

and slightly ridged. It bears the dent of a musket

ball, probably a test mark. Tassets of twelve

plates are attached to the rim of the breastplate

by screws and nuts, the last five plates being remo-

Fig. 8.

vable at pleasure. The greaves and sollerets do

not belong to the harness.

This suit is illustrated on Fig VI.

Number 1146.

This interesting armour marks nearly the latest

stage of an industry that may well be classed

among the fine arts; and on which a wealth of

skill- and ingenuity as well as fine taste and artistic

feeling of the very highest order has been so pro-

fusely lavished. The genius of the renaissance

found in the armourer’s craft, and in those of the

cognate artists the decorator and embellislier, a

Geld of expression perhaps as fascinating and in-

spiring as that afiforded by the painter’s brush or

even the sculptors chisel. The enrichment of ar-

mour of later mediaeval times, and of the earlier

Zeitschrift für historische Waffenkunde.

III. Band.

No. 1098 is a similar armour by the same

Augsburg smith.

No. 1119 is illustrated 011 Fig. V.

Number 474.

On the top of the breastplate is a border

of classic figures and animals; the harness, gene-

rally, is banded boldly in strapwork on a gilt

ground. Tliere is an extra plate over the left

breast and shoulder; and another rises from the

thigh to the centre of the breastplate on that side.

The breastplate, of the peasecod type, is flanged

over the right shoulder; and the lance-rest is small

and folds up. This harness is for Freiturnier

(Free Course), in which a large garde-de-bras

(Stechmäusel) was used in place ofthemanteau

d’armes and the pasgarde1) of Welsches

Gestech. The pasgarde is not present, but the

coude is holed for it.

The difference between welsches Gestech and

Freitournier lay in the circumstance that the

latter was run in the open field or lists, without

a tilt between the jousters. Freiturnier, like

Rennen and Stechen, required more skill and

initiative than did welsches Gestech. The lance

and horse furniture were of the same kind in both

cases, and the body armour of the jousters very

similar; but subject to the interchange of reinforcing

pieces. A suit in the Dresden collection, labelled

v. Holtzendorff is for Freiturnier; as also is that

of Karl Schürft von Schonwert (died 1628). Boeheim

gives an illustration of the last named harness in

liis Waffenkunde as being for das neue welsche

Gestech über das Dill, but I believe this is

not so.

By the commencement of the seventeenth Cen-

tury all the older forms of jousting had fallen into

disuse, with the exception of Freiturnier; and a

sort of skirmish, troop against trepp, called Schar-

mützel. Ringelrennen (running at the ring) also

prevailed greatly, but this game cannot be classecl

as belonging to the tourney.

Number 958.

This suit is without any'very special features

be)mnd the fact that each part is stamped in

numbers, a circumstance suggestive of its having

formed one of a series of armours made to the

same pattern, and possibly of the same size.

A contributing cause to the gradual disuse of

armour was the increasing badness of the fit; and

one sometimes reads of Contemporary complaints

made more especially perhaps after the first half

of the sixteenth Century, of the frequency of badly

fitting plates; which caused great sufifering to the

wearers by reason of the chafing into sores. No

i) This is the real pasgarde (Stechmäuschen); the word

is often used as a clesignation for an upriglit neck guarcl, but

erroneously.

wonder that armour was sometimes thrown away

in a campaign in spite of regulations.

I have illustrated this harness here, more

especially, with a view of giving on these pages

as full a representation as space will allow of the

various styles and periods covered by the collection

as a whole. The suit dates probably in the second

quarter of the seventeenth Century; and rows of

brass-headed rivets follow the lines of the bordering.

The helmet is umbrilled and the breastplate is short

and slightly ridged. It bears the dent of a musket

ball, probably a test mark. Tassets of twelve

plates are attached to the rim of the breastplate

by screws and nuts, the last five plates being remo-

Fig. 8.

vable at pleasure. The greaves and sollerets do

not belong to the harness.

This suit is illustrated on Fig VI.

Number 1146.

This interesting armour marks nearly the latest

stage of an industry that may well be classed

among the fine arts; and on which a wealth of

skill- and ingenuity as well as fine taste and artistic

feeling of the very highest order has been so pro-

fusely lavished. The genius of the renaissance

found in the armourer’s craft, and in those of the

cognate artists the decorator and embellislier, a

Geld of expression perhaps as fascinating and in-

spiring as that afiforded by the painter’s brush or

even the sculptors chisel. The enrichment of ar-

mour of later mediaeval times, and of the earlier