mceRnAcionAL

scudio

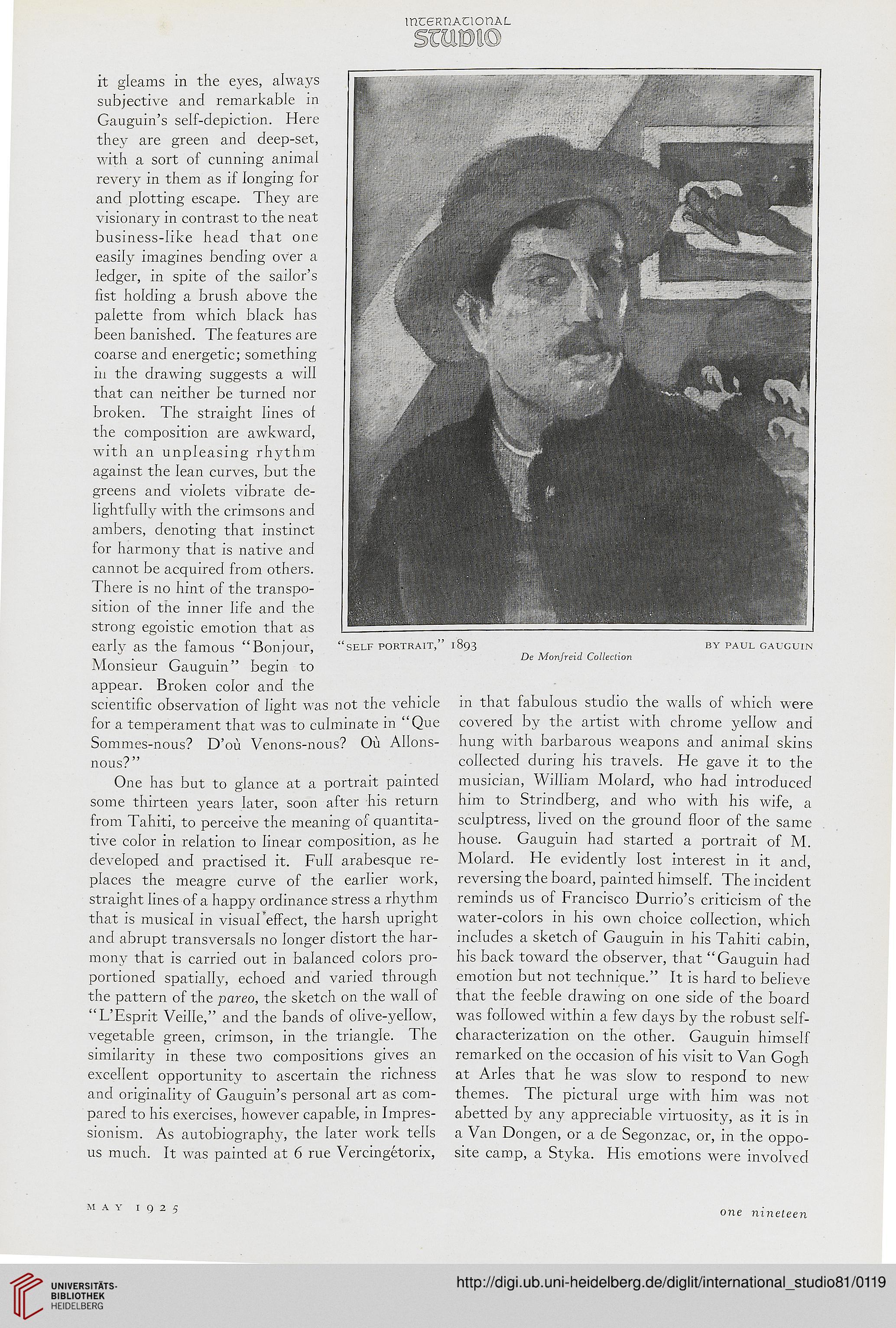

it gleams in the eyes, always

subjective and remarkable in

Gauguin's self-depiction. Here

they are green and deep-set,

with a sort of cunning animal

revery in them as if longing for

and plotting escape. They are

visionary in contrast to the neat

business-like head that one

easily imagines bending over a

ledger, in spite of the sailor's

fist holding a brush above the

palette from which black has

been banished. The features are

coarse and energetic; something

in the drawing suggests a will

that can neither be turned nor

broken. The straight lines of

the composition are awkward,

with an unpleasing rhythm

against the lean curves, but the

greens and violets vibrate de-

lightfully with the crimsons and

ambers, denoting that instinct

for harmony that is native and

cannot be acquired from others.

There is no hint of the transpo-

sition of the inner life and the

strong egoistic emotion that as

early as the famous "Boniour, "self portrait," 1893 / . by paul gauguin

. , , De Monjreid Collection

Monsieur Gauguin" begin to

appear. Broken color and the

scientific observation of light was not the vehicle in that fabulous studio the walls of which were

for a temperament that was to culminate in "Que covered by the artist with chrome yellow and

Sommes-nous? D'oii Venons-nous? Oil Allons- hung with barbarous weapons and animal skins

nous?" collected during his travels. He gave it to the

One has but to glance at a portrait painted musician, William Molard, who had introduced

some thirteen years later, soon after his return him to Strindberg, and who with his wife, a

from Tahiti, to perceive the meaning of quantita- sculptress, lived on the ground floor of the same

tive color in relation to linear composition, as he house. Gauguin had started a portrait of M.

developed and practised it. Full arabesque re- Molard. He evidently lost interest in it and,

places the meagre curve of the earlier work, reversing the board, painted himself. The incident

straight lines of a happy ordinance stress a rhythm reminds us of Francisco Durrio's criticism of the

that is musical in visual'effect, the harsh upright water-colors in his own choice collection, which

and abrupt transversals no longer distort the har- includes a sketch of Gauguin in his Tahiti cabin,

mony that is carried out in balanced colors pro- his back toward the observer, that "Gauguin had

portioned spatially, echoed and varied through emotion but not technique." It is hard to believe

the pattern of the pareo, the sketch on the wall of that the feeble drawing on one side of the board

"L'Esprit Veille," and the bands of olive-yellow, was followed within a few days by the robust self-

vegetable green, crimson, in the triangle. The characterization on the other. Gauguin himself

similarity in these two compositions gives an remarked on the occasion of his visit to Van Gogh

excellent opportunity to ascertain the richness at Aries that he was slow to respond to new

and originality of Gauguin's personal art as com- themes. The pictural urge with him was not

pared to his exercises, however capable, in Impres- abetted by any appreciable virtuosity, as it is in

sionism. As autobiography, the later work tells a Van Dongen, or a de Segonzac, or, in the oppo-

us much. It was painted at 6 rue Vercingetorix, site camp, a Styka. Flis emotions were involved

may i q 2 5

one nineteen

scudio

it gleams in the eyes, always

subjective and remarkable in

Gauguin's self-depiction. Here

they are green and deep-set,

with a sort of cunning animal

revery in them as if longing for

and plotting escape. They are

visionary in contrast to the neat

business-like head that one

easily imagines bending over a

ledger, in spite of the sailor's

fist holding a brush above the

palette from which black has

been banished. The features are

coarse and energetic; something

in the drawing suggests a will

that can neither be turned nor

broken. The straight lines of

the composition are awkward,

with an unpleasing rhythm

against the lean curves, but the

greens and violets vibrate de-

lightfully with the crimsons and

ambers, denoting that instinct

for harmony that is native and

cannot be acquired from others.

There is no hint of the transpo-

sition of the inner life and the

strong egoistic emotion that as

early as the famous "Boniour, "self portrait," 1893 / . by paul gauguin

. , , De Monjreid Collection

Monsieur Gauguin" begin to

appear. Broken color and the

scientific observation of light was not the vehicle in that fabulous studio the walls of which were

for a temperament that was to culminate in "Que covered by the artist with chrome yellow and

Sommes-nous? D'oii Venons-nous? Oil Allons- hung with barbarous weapons and animal skins

nous?" collected during his travels. He gave it to the

One has but to glance at a portrait painted musician, William Molard, who had introduced

some thirteen years later, soon after his return him to Strindberg, and who with his wife, a

from Tahiti, to perceive the meaning of quantita- sculptress, lived on the ground floor of the same

tive color in relation to linear composition, as he house. Gauguin had started a portrait of M.

developed and practised it. Full arabesque re- Molard. He evidently lost interest in it and,

places the meagre curve of the earlier work, reversing the board, painted himself. The incident

straight lines of a happy ordinance stress a rhythm reminds us of Francisco Durrio's criticism of the

that is musical in visual'effect, the harsh upright water-colors in his own choice collection, which

and abrupt transversals no longer distort the har- includes a sketch of Gauguin in his Tahiti cabin,

mony that is carried out in balanced colors pro- his back toward the observer, that "Gauguin had

portioned spatially, echoed and varied through emotion but not technique." It is hard to believe

the pattern of the pareo, the sketch on the wall of that the feeble drawing on one side of the board

"L'Esprit Veille," and the bands of olive-yellow, was followed within a few days by the robust self-

vegetable green, crimson, in the triangle. The characterization on the other. Gauguin himself

similarity in these two compositions gives an remarked on the occasion of his visit to Van Gogh

excellent opportunity to ascertain the richness at Aries that he was slow to respond to new

and originality of Gauguin's personal art as com- themes. The pictural urge with him was not

pared to his exercises, however capable, in Impres- abetted by any appreciable virtuosity, as it is in

sionism. As autobiography, the later work tells a Van Dongen, or a de Segonzac, or, in the oppo-

us much. It was painted at 6 rue Vercingetorix, site camp, a Styka. Flis emotions were involved

may i q 2 5

one nineteen