mceRnAcionAL

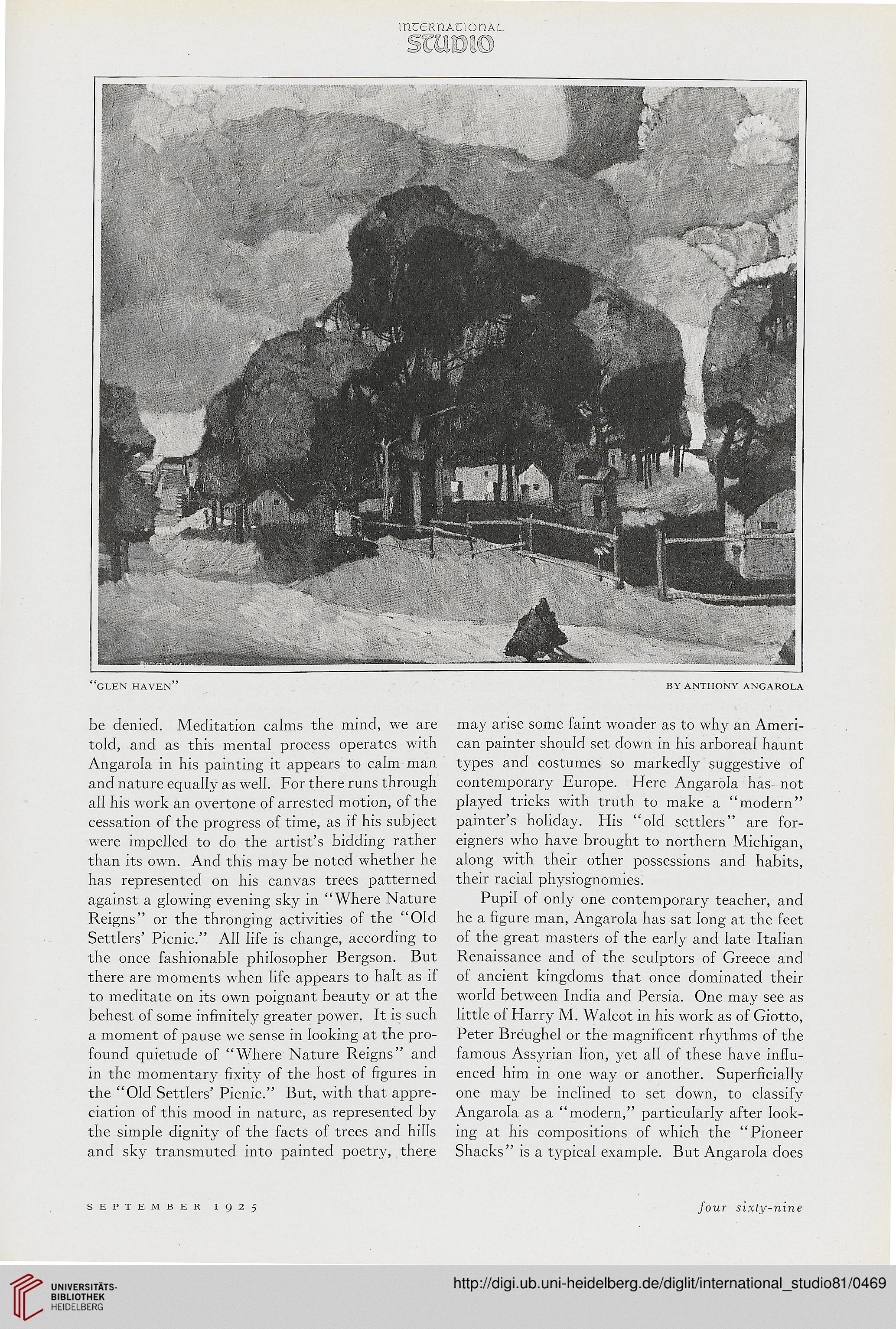

GLEN HAVEN BY ANTHONY ANGAROLA

be denied. Meditation calms the mind, we are

told, and as this mental process operates with

Angarola in his painting it appears to calm man

and nature equally as well. For there runs through

all his work an overtone of arrested motion, of the

cessation of the progress of time, as if his subject

were impelled to do the artist's bidding rather

than its own. And this may be noted whether he

has represented on his canvas trees patterned

against a glowing evening sky in "Where Nature

Reigns" or the thronging activities of the "Old

Settlers' Picnic." All life is change, according to

the once fashionable philosopher Bergson. But

there are moments when life appears to halt as if

to meditate on its own poignant beauty or at the

behest of some infinitely greater power. It is such

a moment of pause we sense in looking at the pro-

found quietude of "Where Nature Reigns" and

in the momentary fixity of the host of figures in

the "Old Settlers' Picnic." But, with that appre-

ciation of this mood in nature, as represented by

the simple dignity of the facts of trees and hills

and sky transmuted into painted poetry, there

may arise some faint wonder as to why an Ameri-

can painter should set down in his arboreal haunt

types and costumes so markedly suggestive of

contemporary Europe. Here Angarola has not

played tricks with truth to make a "modern"

painter's holiday. His "old settlers" are for-

eigners who have brought to northern Michigan,

along with their other possessions and habits,

their racial physiognomies.

Pupil of only one contemporary teacher, and

he a figure man, Angarola has sat long at the feet

of the great masters of the early and late Italian

Renaissance and of the sculptors of Greece and

of ancient kingdoms that once dominated their

world between India and Persia. One may see as

little of Harry M. Walcot in his work as of Giotto,

Peter Breughel or the magnificent rhythms of the

famous Assyrian lion, yet all of these have influ-

enced him in one way or another. Superficially

one may be inclined to set down, to classify

Angarola as a "modern," particularly after look-

ing at his compositions of which the "Pioneer

Shacks" is a typical example. But Angarola does

SEPTEMBER I 9 2 5

Jour sixty-nine

GLEN HAVEN BY ANTHONY ANGAROLA

be denied. Meditation calms the mind, we are

told, and as this mental process operates with

Angarola in his painting it appears to calm man

and nature equally as well. For there runs through

all his work an overtone of arrested motion, of the

cessation of the progress of time, as if his subject

were impelled to do the artist's bidding rather

than its own. And this may be noted whether he

has represented on his canvas trees patterned

against a glowing evening sky in "Where Nature

Reigns" or the thronging activities of the "Old

Settlers' Picnic." All life is change, according to

the once fashionable philosopher Bergson. But

there are moments when life appears to halt as if

to meditate on its own poignant beauty or at the

behest of some infinitely greater power. It is such

a moment of pause we sense in looking at the pro-

found quietude of "Where Nature Reigns" and

in the momentary fixity of the host of figures in

the "Old Settlers' Picnic." But, with that appre-

ciation of this mood in nature, as represented by

the simple dignity of the facts of trees and hills

and sky transmuted into painted poetry, there

may arise some faint wonder as to why an Ameri-

can painter should set down in his arboreal haunt

types and costumes so markedly suggestive of

contemporary Europe. Here Angarola has not

played tricks with truth to make a "modern"

painter's holiday. His "old settlers" are for-

eigners who have brought to northern Michigan,

along with their other possessions and habits,

their racial physiognomies.

Pupil of only one contemporary teacher, and

he a figure man, Angarola has sat long at the feet

of the great masters of the early and late Italian

Renaissance and of the sculptors of Greece and

of ancient kingdoms that once dominated their

world between India and Persia. One may see as

little of Harry M. Walcot in his work as of Giotto,

Peter Breughel or the magnificent rhythms of the

famous Assyrian lion, yet all of these have influ-

enced him in one way or another. Superficially

one may be inclined to set down, to classify

Angarola as a "modern," particularly after look-

ing at his compositions of which the "Pioneer

Shacks" is a typical example. But Angarola does

SEPTEMBER I 9 2 5

Jour sixty-nine